Sokal

Alternate names and spellings: Sokal (Polish), Sokal' (Ukranian), Сокаль (Russian), Sikal (Yiddish), Skol (German), Skul

Sokal, where the Katz branch of my family originally came from, including my mother, grandfather and great-grandfather.

Background

Sokal is a little town in what was formerly known as Eastern Galicia.

After the Treaty of Versailles, and by the time Toni was born, it had become part of the newly reborn Poland. During WWII, it was annexed to the Ukraine Soviet Socialist Republic, then was invaded by Germany in 1941. It was finally liberated by the Russian army in July 1944. Today, it is part of Ukraine.

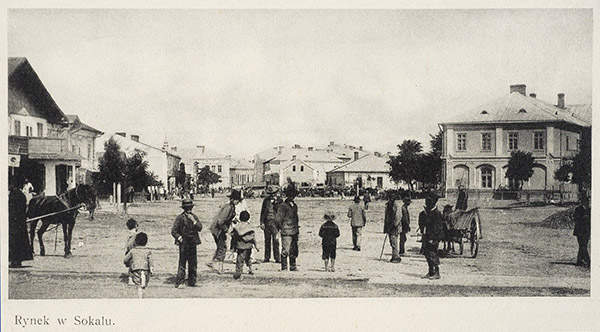

Map of Eastern Galicia, 1895.

The town is 75 km from Lvov (Lemberg in German, Lviv in Ukrainian) and is located on the banks of the river Bug, a shallow little river which marked the border between the Russian and German sectors of Poland during WWII.

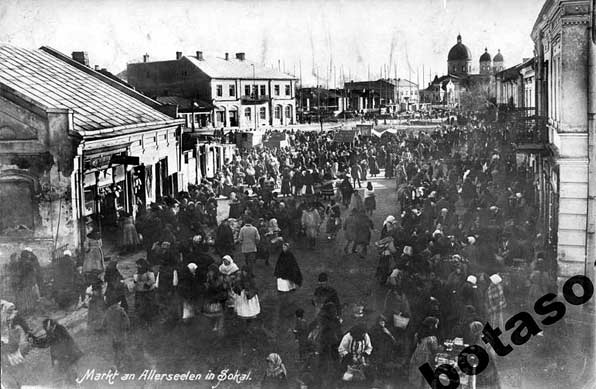

Sokal Scenery

The river Bug in Sokal, hand colored postcard, 1910

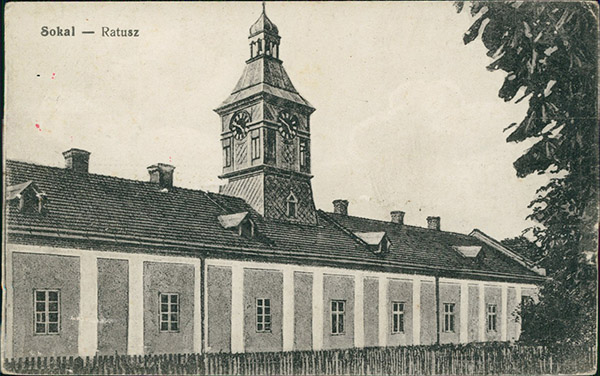

Sokal Town Hall, 1916

Sokal: Towarzystwo Zaliczkowe (lending company/credit union?), 1915

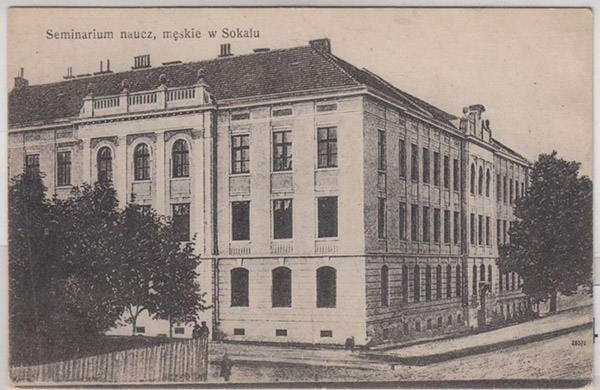

Teachers Seminary in Sokal

Sokal High School

Jewish presence in Sokal

The earliest known Jewish community dates back to the 16th century. Jews settling in the early 17th century likely arrived from neighboring Belz, whose Hasidic court set the tone of Jewish life in Sokal from early 19th century.

As in many other towns in Poland's eastern borderlands during the 16th and 17th centuries, a fortified synagogue was erected in the Jewish quarter, to help contribute to the town's defensive system.

Rare pre-war photo of the Sokal Synagogue.

"Two synagogues were located on one land property; the door on the very right of the photo is to the second synagogue." (Alex Den)

Postcard courtesy of Fran Fay Letzter Malkin.

The Fortress Synagogue - 1930

The Old Synagogue of Sokal. Late 17th-early 18th century, with late 19th century extension. Photo before 1931

Source: Ars Judaica, via rtrfoundation.org

Jews constituted an urban class trading mainly in farm produce. During the period of Austrian rule, from 1772 to 1918, the Jews were mainly occupied in small commerce, crafts, and transportation. In the early 20th century, five of the six brickyards in Sokal were owned by Jews, as well as plywood, soap and candle factories, sawmills and printing presses.

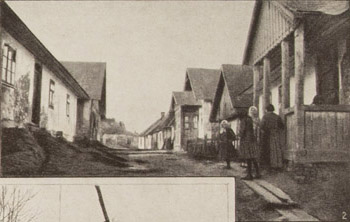

Sokal Jewish Quarter

Postcard, ca 1916/1917. Courtesy of František Bányai at judaica.cz. Please do not copy; contact the owner for any use.

Hasidism had considerable influence within the community. Later, between the two world wars, Zionism played an important role in community life.

In the 19th and 20th century, Jews represented over 40% of Sokal's population. In 1921, the total population was 10,183, with 43% Jews - Jewishgen.com gives an even higher estimate of approximately 50% of the total population. In 1931, the Jewish population was estimated to be 5,450.

Sokal Street Scene, 1916-1918

Source: Österreichisches Staatsarchiv (Austrian State Archives), via photo-lviv.in.ua

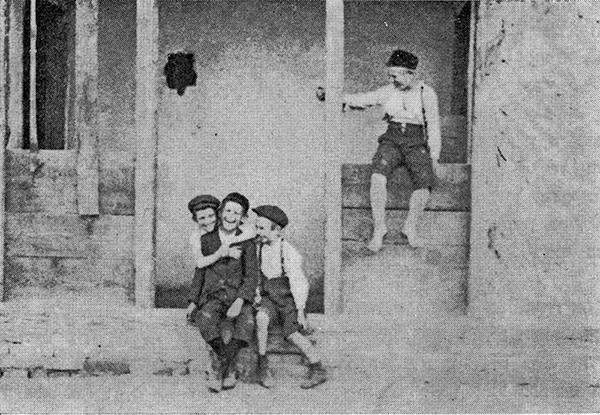

Heder children, Sokal

Source: Sokal Yizkor book, p. 20

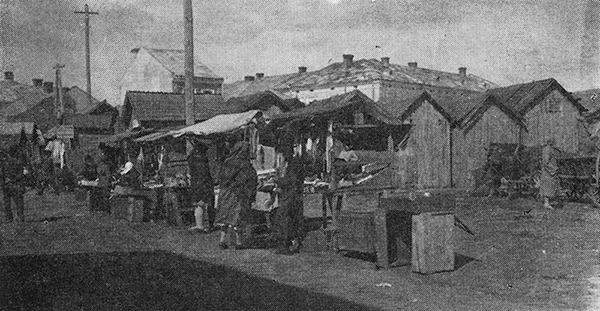

"Stalls in Old Sokal"

Source: Sokal Yizkor book, p.55

Osias (Yehoshua) Lieber's shop in Sokal, opened in 1878.

Source: Sokal Yizkor book, p.59

The Baron Hirsch street in Sokal.

Source: Sokal Yizkor book, p.100

The Baron Hirsch street in Sokal, 1916-1918

Note the two Austrian officers in the foreground, right.

Source: myshtetl.org

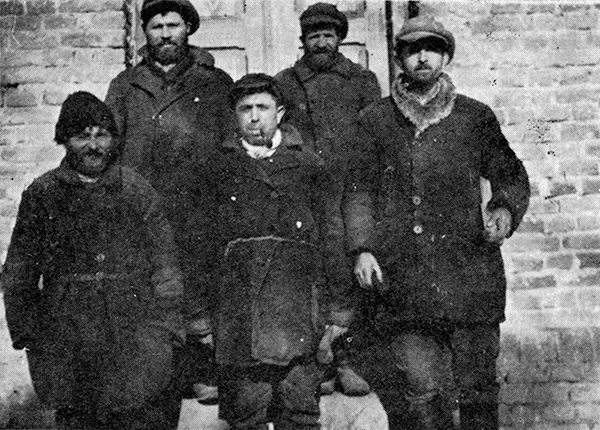

Jewish Porters in Sokal.

Source: Sokal Yizkor book, p.90

Sokal during WWI

On August 1914, ten days after Germany declared war on France, the Russian cavalry entered Galicia at Sokal on the Bug and defeated the Austrians, who retreated in the direction of Lemberg.

"In one of the first engagements on the Eastern Front, 300,000 Austrian troops advanced from Lemberg (L'vov) in preparation for the invasion of Russia. Russia had mobilized two armies - over 700,000 Russian troops attacked on August 13th, 1914, defeating the Austrians and forcing them to retreat back to Lemberg."

During the war, the region saw frequent fighting between the Austro-Hungarian troops and the Russian army, which left it devastated. The Jewish population in particular was the frequent target of pogroms from both armies.

S.Ansky, the Jewish playright and journalist, spent the war following the Russian army throughout the Pale of Settlement, organizing relief for the Jewish populations, who often became refugees running away from the battlefields. He documented what he saw in "The Enemy at this pleasure". Here are a few excerpts that describe the effects of the war on Sokal and its region:

Galicia is one of the poorest regions of Central Europe, if not the poorest. The soil is not particularly fertile, the farming methods are primitive and the harvests meager. Industry, manufacture, and commerce are also underdeveloped...

The Galician Jews numbered between 900 thousand and one million before the war (WW1).

Even though Jews in the Austrian Empire enjoy equal rights, with equal access to all the professions and government jobs, those in Galicia are very poor and unsophisticated.... Galicia has the highest death rate among jews and the highest rate of immigration to America.

Galician Jews clearly lag behind other communities in cultural terms as well... Galicia's Hasidism degenerated into blind faith in wonder rabbis, while Orthodoxy waged an especially savage and relentless war against the Enlightment, and assimilation here has been a poor joke...

Right after the outbreak of the hostilities (WWI), the Russian army overran Galicia... There were .. reports that the Russians, especially the Cossacks, were savaging the Jewish population in these occupied areas.

In Brody, the troops ... burned down a huge portion of the city, pillaged homes, and massacred several Jews. They also razed Husiatyn and Belz.

In Lwow, a pogrom claimed a large number of victims. Similar rumors were heard about dozens of other towns, and in the conquered regions, the Jews, economically ruined and cut off from both Austria and Russia, were starving to death.

(Belz is a town next to Sokal, and Lwow was the district center to which Sokal belonged)... When the Russian army pased through many towns and villages, especially when there were cossacks, bloody pogroms took place...

A pogrom took place in Sokal:

During the pogrom in Sokal, Jewish soldiers (from the Russian army) either joined the cossacks in taking merchandise from stores or asked them for a portion of the loot, which they then returned to the owners.

In June 1915, as the Russians retreated from Galicia, S.Ansky followed a Russian mobile medical unit set up in Sokal. On his way there, in Kovel, he saw several dozens of Jewish refugees from Sokal sitting on the ground in the station courtyard and asked:

What happened in Sokal?

They beat up the Jews and ransacked their stores. The Commander ordered his men to take the merchandise. No one else (no Christian) was bothered

A little later, he entered Sokal and wrote:

Sokal is a large town and was apparently once rich and beautiful.

... There was a deadly hush, the stores were all closed, and I couldn't tell whether that was because of the Sabbath or the recent pogrom. On closer inspection, I saw the battered doors, the smashed windows, the twisted, ripped-out metal doors. The interiors were all in shambles-torn, gutted, riddled with bullets.

I couldn't find any Jews... no troops to be seen, just poor Jewish homes. A bit farther, a huge, ancient synagogue from the seventeenth century-one of the most beautiful I had seen.

Women, children, and old people were sitting all around it, with drooping heads, as if they were mourning the temple.

He learned that a pogrom had taken place in Sokal, all the stores had been looted, many were injured and one person had been killed. The synagogue was left undamaged.

The elderly Jewish owner of the hotel where he was staying told S.Ansky:

They destroyed Sokal. They spent the whole week looting, smashing, beating. They didn't leave one home or store untouched.

Maybe a few hundred Jews were slaughtered or mutilated... There are orphans in the woods, and no one knows what happened to their mothers...

They began by rounding up all the Jewish men in the square, about a thousand, and they said they would shoot them all. Then they said they would send them to Russia...

The Jews collected a few thousand rubles and brought the money to the commander. So he took just seventy-five men and packed them off to Russia, and the rest he let go.

A little later, with the news that Belz was taken by the Austrians:

... Sokal was evacuated (by the Russian army). At night, Sokal was encircled by the fire of towns and villages burning nearby. Throughout the next day, Sokal was surrounded by pillars of smoke from the burning towns and villages.

Austro-Hungarian troops crossing the Bug River near the city of Sokal on July 18, 1915.

@ThisDayInWWILater, the Russian troops were back again in Sokal.

The town itself was still the dismal wreck it had been a few days earlier. Not a shop was open. However, there were two or three small tables with bread set up in the street. Troops clustered there, buying up the bread. Others, wandering around, were angry because they could find nothing to buy. So of course they blamed the Jews.

I went back to the hotel where I had stayed before. The proprietor told me the pogrom had kept raging these past few days.

S.Ansky travelled to Galicia again between December 1916 and early March 1917, and noted that the situation of the Jewish population had improved somewhat, mainly due to the Russia's defeats which

... brought an end to the mass expulsions of Jews from the front line. Soon the Pale of Settlement would be abolished altogether. The government itself was now doling out funds to aid the deportees.

... people learned the truth about Russia's cruelties and atrocities in Galicia... This move gradually brought an end to the systematic error of the population, especially the Jews.

... In several places they relaxed or even rescinded the travel ban, which had afflicted Jews almost exlusively. Some refugees returned to Sokal...

... The civil autority often took its own measures to supply medical aid and food, and enable people to rebuild their homes. Officially, this was motivated by the fear of epidemics, which could spread to the army. Of course, the situation was still far from ideal. Jews were still being dragged off to forced labor, bribes were still extorted, and hatred was openly displayed...

Finally, some refugees returned to Sokal, and in in February 1917, S.Ansky, in charge of relief work for Jews who had suffered because of the war, declared that they should be

... focussing on reviving the shtetls to which the Jews were returning. Assistance could be stopped altogether in places like Sokal, where a few inhabitants had come back and set themselves up with no outside help

The Polish-Russian War (1919-1921)

Soon after the end of WWI, which had brought widespread destruction to Galicia, a new armed conflict took place again in the region: the Polish-Soviet War (February 1919 - March 1921).

Poland's goal was to secure territories which she had lost at the time of partitions; the Soviet's aim was to control those same territories, which had been part of Imperial Russia, and to spread communism to the West.

Galicia once again became the theater for battles, its Jewish population suffering the violent pogroms from both armies. The region was just emerging from a devastating period of pogroms and wartime occupation when the Polish-Soviet fighting began.

Isaac Babel, a Jewish writer embedded with the Red Army during the Polish-Russian War, reported on the misery and violence he witnessed in the Jewish towns and villages of Galicia. He was in Sokal between August 25 and 27, 1920, and described his impressions in his "Red Cavalry Stories" and "1920 Diary". (At the time of the events described by Babel, my mother was about 11 months old.)

Excerpts from his 1920 Diary:

"AUGUST 25, 1920. SOKAL"

"The infantry has been in Sokal, but the town is untouched, the divisional chief of staff is billeted with some Jews. Books, I saw books. I'm billeted with a Galician woman, a rich one at that, we eat well, chicken in sour cream.

I ride on my horse to the center of town, it's clean, handsome buildings, everything messed up by war, but remnants of cleanliness and a character of its own.

The Revolutionary Committee. Requisitions and confiscation. Interesting: they don't touch the peasantry, all the land has been left at its disposal. The peasantry is left alone.

My landlord's son - a Zionist and vehement nationalist. Normal Jewish life, some feel the pull of Vienna, Berlin. Tthe nephew, a young man, is studying philosophy, wants to go to the university. We eat butter and chocolate.

[...] In the evening, the division commander in his new jacket, well fed, wearing his multicolored trousers, red-faced and dim-witted, out to have some fun, music at night, the rain disperses us.

It is raining, the tormenting Galician rain, it pours and pours, endlessly, hopelessly."

August 26, 1920. SOKAL

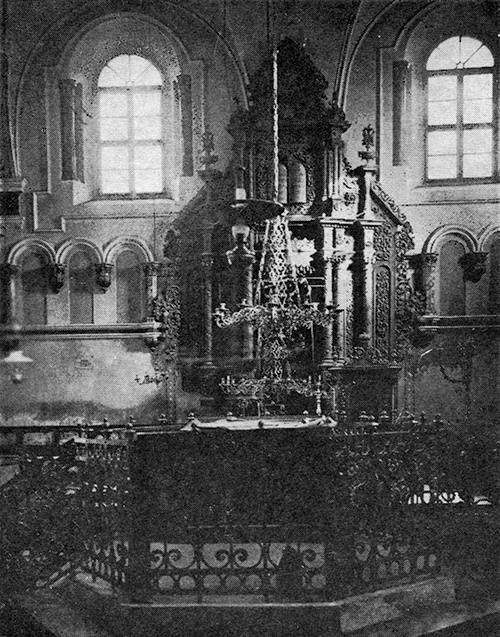

The synagogues: the Hasidic one is an amazing sight, it recalls three hundred years ago, pale, handsome boys with peyes, the synagogue as it was two hundred years ago, the same figures in long coats, swaying, waving their arms, wailing.

This is the Orthodox party, they support the Rabbi of Belz, the famous Rabbi of Belz, who's made off to Vienna. The moderates support the Rabbi of Husyatin. Their synagogue. The beauty of the altar made by some artisan, the magnificence of the greenish chandeliers, the worm-eaten little tables, the Belz synagogue - a vision of ancient times.

The Jews ask me to use my influence so they won't be ruined, they're being robbed of food and goods. The Jews hide everything. The cobbler, the Sokal cobbler, is a proletarian. His apprentice's appearance, a red-haired Hasid - a cobbler. The cobbler has been waiting for Soviet rule - now he sees the Yid-killers and the looters, and that there'll be no earnings, he is shaken, and looks at us with distrust. A commotion over money. In essence, we're not paying anything, 15-20 rubles.

The Jewish quarter. Indescribable poverty, dirt, the fenced-in quality of the ghetto. The little shops, all of them open, soldiers ransacking, cursing the Yids, drifting around aimlessly, entering homes, crawling under counters, greedy eyes, a strange army indeed.

At night the town will be looted - everyone knows that.

A chat with the nephew who wants to go to university. Sokal: brokers and artisans - Communism, they tell me, isn't likely to strike root here.

What battered, tormented people these are. Poor Galicia, poor Jews.

In "Squadron Commander Trunov", from "The Red Cavalry Stories", Babel described street scenes in Sokal reminiscent of a Chagall painting, including a quarrel between Jews in the square in front of the synagogue ("Religious carnage, you'd think you were in the eighteenth century"):

"[I] left to go for a walk through the town, through gothic Sokal, which lay in its blue dust and in Galicia's dejection. A large square stretched to the left of the park, a square surrounded by ancient synagogues. Jews in long, torn coats were cursing and shoving each other on this square. Some of them, the Orthodox, were extolling the teachings of Adassia, the Rabbi of Belz, which led the Hasidim of the moderate school, students of Rabbi Iuda of Husyatyn, to attack them. The Jews were arguing about the Kabbala, and in their quarrel shouted the name of Elijah, Gaon of Vilna, the persecutor of the Hasidim. Ignoring war and gunfire, the Hasidim were cursing the name of Elijah, the Grand Rabbi of Vilna [...] "

"[...] I suddenly saw a Galician before me, sepulchral and gaunt as Don Quixote. This Galician was wearing a white linen garment that reached down to his ankles. He was dressed as for burial or as for the Eucharist, and led a bedraggled little cow tied to a rope. The pitiful little cow tagged along behind the Galician. He led her with importance, and his lanky body cut into the hot brilliance of the sky like a gallows.

He crossed the square with a stately stride and went into a crooked little alley seasoned with sickeningly thick smoke. In the charred little hovels, in beggarly kitchens, were Jewesses who looked like old Negro women, Jewesses with boundless breasts.

The Galician walked past them and stopped at the end of the alley before the pediment of a shattered building. There by the pediment, near a crooked white column, sat a gypsy blacksmith shoeing horses. The gypsy was pounding the horses' hooves with a hammer, shaking his greasy hair, whistling, and smiling. A few Cossacks with horses were standing around him. My Galician walked up to the blacksmith, gave him a dozen or so baked potatoes without a word, and turned and walked off, not looking up at anyone."

The Interwar Period

From Yad Vashem:

In the 1930s, about 5,200 Jews lived in Sokal, about half of its population. Along with merchants and craftsmen, the Jews of Sokal also owned factories for light industry and professionals. A commercial bank and several welfare societies operated there. The Jewish educational institutions in the city included traditional classrooms, the Beit Yaakov school and the Hebrew school of the Tarbut network (secular Zionist).

WW2 - The Russian Occupation

Note: most of the content below was sourced from Yad Vashem.

From September 1939 until June 1941 (Operation Barbarossa), Sokal was occupied by the Soviet Union. During the Soviet rule, factories were nationalized, commerce was greatly reduced, and Jewish parties were abolished. In the summer of 1940 several bourgeois families were deported to the rest of the Soviet Union, as were some refugees who refused to accept Soviet citizenship.

WW2 - The German Occupation

On June 23, 1941, the Germans occupied Sokal. A few days later, the Germans, with the help of Ukrainian nationalists rounded up 400 Jews, and after a selection, murdered most of them near the brickyard outside the town.

In July 1941, the Germans appointed a Judenrat which was tasked with supplying hundreds of Jews daily for forced labor. In November 1941, all the Jewish men between the ages of 14 and 60 were registered in the German Labor Office. Forced labor followed with starvation claimed many lives in the winter of 41/42.

On September 17, 1942, the first mass Aktion took place in Sokal. German and Ukrainian police blocked the outskirts of the city, combed the Jewish houses and took their inhabitants to the market square; Some 2,000 Jews were deported to the Belzec death camp, while about 160 were murdered on the town square.

A month later, 0n October 15, a ghetto was set up for remaining Sokal Jews, with an additional 3,000 Jews rounded up from surrounding settlements such as Radziechow, bringing the total population of the overcrowded ghetto to over 5,000.

On October 28, about two weeks after the establishment of the ghetto, a second "Aktion" took place, and 2,500 Jews were deported to the death camp of Belzec. Many attempted to escape but were killed by the Germans with the help of the hostile local population, including roaming gangs of Ukrainian nationalists.

After the two Aktions, an increasing number of Jews attempted to escape from the ghetto to the forests or to Christian acquaintances, but the hostile environment, including bands of Ukrainian nationalists, and the Germans' search, made rescue efforts very difficult. In the ghetto itself, the difficult sanitary conditions continued to cause many casualties - the number of people who died in the ghetto in the winter of 1942/43 was estimated to be about 1,500.

In the spring of 1943, groups of Jews who wandered through the forests began to leave their hiding places and returned to the ghetto in Sokal, following news that the Germans had distributed them to vital factories.

The Aktion for the final liquidation of the ghetto began on May 27, 1943. During the Aktion, attempts were made to organize a mass escape, but most of the escapees were shot on the spot and buried in the local cemetery. The remaining ghetto residents were taken to pits about three kilometers outside of the city and executed there.

Save for some thirty Jews who had managed to survive in hideouts and in the nearby forests, Sokal was "Judenrein", its entire Jewish population, which had numbered about 6,000 before the war, having been killed, or deported to the death camp of Belzec. Of the survivors, fifteen Jews lived through the war thanks to two extraordinary women, Francisca and Hela Halamajowa, who hid them for 20 months in their home. See the documentary No. 4 Street of Our Lady about their story.

See also the story of Ralph Israel Charak who survived by hiding in the forest.

The Soviet army re-captured the town in July 1944.

Further notes on the destruction of the Jewish community in Sokal.

Fran Fay Letzter Malkin, who was born in Sokal and was hidden for 18 months along with her family by Francisca Halamajowa, wrote (via the Jews who come from Sokal FB group):

"My father, Eli Letzter, was killed when the Germans came into Sokal and ordered all Jewish males to report for work and they selected 400 and took them out to an old brick factory and shot them."

Yahad-In Unum is an organization dedicated to locating the sites of mass graves of Jewish victims of the Nazi mobile-killing units in the former Soviet Union founded by Patrick Desbois. Here are their findings regarding mass executions of Jews in Sokal: (via Fran Fay Letzter Malkin / Jews who come from Sokal FB group).

"According to the Soviet extraordinary commission conducted just after the liberation and the German archives, there were four executions in June 1941. The first one was conducted on June 22, 1941, the same day the village was occupied, against 11 Jews who were shot dead in front of Polish cathedral. Then, there were three more in the course of three days, from June 28 to June 30, when 17 Jews, 117 Jews and 183 Jews were shot respectively. Prior to the execution all those Jews were confined in the brick factory and then murdered not far from it. [The information about what happened to them before the shooting is different from Moshe Maltz's memoir.] Unfortunately, we didn’t find any eyewitnesses to this shooting or to what happened before. But this execution site normally had a memorial at the time of our investigations and it is located by the road leading to Tartakiv."

"There were several deportation waves, one deportation as conducted on September 17, 1942, when 2,000 Jews were deported to Belzec and about 160 shot dead of the spot. Another one was conducted after the ghetto was established in Sokal in late October when about 4,000 Jews were deported. The ghetto was liquidated on May 27, 1943. During the liquidation some 3,000 Jews were shot, according to the Soviet archives but this number might be overestimated. According to the local witness, the shooting was conducted in field located between Sokal and Ravshchina. The shooting was conducted during the day and the road was blocked in order to prevent the collateral victims, so some people were stopped on the road and could hear what was happening until the execution was over."

Rescues

Amid the numerous tales of mass killings, deportations and of the destruction of the Jewish community from Sokal, three instances of survival and rescues deserve to be told.

One such story is the heroic rescue of 15 Jews from Sokal by Francisca Halamajowa, a Polish-Catholic woman who hid them for almost two years in her pigsty. Judy Maltz, the grand-daughter of one of the people who were saved by Halamajowa, directed No. 4 Street of Our Lady, a documentary based on her grand-father's diaries. Francisca Halamajowa and her daughter Helena were recognized as Righteous Among the Nations.

Another extraordinary tale of courage and survival against the odds is the story of Ralph Israel Charak, who survived the liquidation of the Sokal ghetto and escaped into the forests, where he hid until the end of the war. His story was written by his grand-daughter Sarah.

Yet another unique story related to Sokal is the rescue account of Antonia ("Tosca") Gruber, a Lwow native, by Nestor Zenon Sniadanko, a Catholic Ukrainian, originally from Sokal. Antonia ("Tosca") Gruber, then a 26-year old woman, was hidden by Nestor Zenon Sniadanko in his one-room apartment in Lwow for almost two years, from 1942 to 1944. After the war the two married and made their way to the displaced persons camp in Rosenheim, Bavaria. In 1947 their only son, Fredi, was born, and a year later they immigrated to Israel. Nestor Zenon Sniadanko changed his name to Joseph Gruber. He was recognized as a Righteous Among the Nations. (Obituary by Yossi Sarid. (jpg); Obituary by Yossi Sarid - Haaretz link).

Today

Today, there are fewer than 10 Jews out of a total population of over 25,000 people. What was once the center of the Jewish community of Sokal is now a park, the ancient fortress synagogue is in ruins, while the former Jewish cemetery is a residential zone with no signs or markers (source: jewishheritage.org.ua (pdf)).

Fredi Gruber, whose father, Nestor Zenon Sniadanko, a Catholic Ukrainian, hid his Jewish mother, Antonia Gruber, reported:

"I have heard about the killing fields in the forests surrounding Sokal from my Ukrainian relatives. Human remains come up to the surface when the area is overflooded."

The old Fortress Synagogue

The Fortress Synagogue in Sokal was built in 1762 and is reputedly one of the oldest ones in Galicia. It is now falling apart and beyond repair.

Sokal Synagogue

Source: Yizkor book

Sokal Synagogue, 2014

Photo courtesy of Christian Herrmann. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Color photos above originally retrieved from www.geocities.com/prysjan/ind_10_sokal.html and www.zapala.pl/eb/ukra2002/zdj-21.htm (dead links as of 2017)

Jewish tombstones and former Jewish quarter.

The Jewish cemetery in Sokal is no more - in its place is a residential area with no signs or markers.

Sokal Tombstones, 2015

Photo courtesy of Christian Herrmann. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Sokal Tombstones, 2015

Photo courtesy of Christian Herrmann. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Tombstones from the ruined Jewish cemetery dumped in the partly ruined Polish cemetery, Sokal, Ukraine, 2014

Photo courtesy of Jason Francisco.

Recovered Jewish tombstones deposited in the town's abandoned Polish Catholic cemetery. The town's Jewish cemetery no longer exists, having been completely overbuilt with new housing.

Photo courtesy of Jason Francisco.

Once the center of the ancient Jewish community of Sokal, later the heart of Nazi-made Jewish ghetto, completely razed and now a public park with no historical marker whatsoever.

Photo courtesy of Jason Francisco.

Sokal today

Sokal on the river Bug

The river Bug

The river Bug

Sokal by the river Bug

- Special Thanks:

- I am indebted to all the authors, researchers, translators and diarists who documented the story of Sokal. This page would not exist without their work.

- I am particularly indebted to the photographers and collectors who are documenting what remains of a vanished world and who graciously allowed me to use their photos of Sokal on this page:

- Christian Herrmann: https://vanishedworld.blog/

- Jason Francisco: http://jasonfrancisco.net/

- František Bányai: judaica.cz for allowing me to use his photograph of the old Jewish Quarter.

- Special Thanks:

- Fredi Gruber, the son of Nestor Zenon Sniadanko and Antonia Gruber, for sharing the story of his mother's survival thanks to his father's heroic actions.

- Links:

- Jewishgen

- www.jri-poland.org

- Photos on Kehilalinks.jewishgen.org

- Pages about Pain and Death of the Jewish Settlement in Sokal, by Moshe Maltz

- Yad Vashem article on Sokal (Hebrew)

- קבוצת יוצאי סוקאל -- Jews who come from Sokal (Facebook Group)

- Yizkor Book:

-

Sefer Sokal, Tartakov, Varenzh, Stoyanov Ve-ha-Seviva: Memorial Book of Sokal, Tartakov, Varenzh, Stoyanov and Surroundings.

Hebrew & Yiddish. 576 pp, with photos.

Abraham Chomet, Ed.

Published by Irgun yots'e Soḳal ṿeha-seviva, Tel Aviv, 1968. - Digital Versions (online viewer, pdf, text versions): yiddishbookcenter.org

- List of translated pages: Memorial Book of Sokal, Tartakow and Surroundings

- Sokal during WW1:

-

The Red Cavalry Stories and Sketches for the Red Cavalry Stories,

1920 Diary, Isaac Babel.

Include descriptions of Sokal during the Polish-Russian war, at a time when my grandmother and mother were most likely still living in Sokal. (August 25 to 27, 1920). -

The Enemy at his Pleasure S. Ansky.

Several mentions of Sokal during WWI, including descriptions of pogroms and the flight of refugees. More generally, the book also describes the effect the war had on the Jewish population of Galicia, most notably the terror from the Cossacks. -

The Good Soldier Švejk, Jaroslav Hašek.

Satirical novel, with references to the fighting in and around Sokal during WW1. - Zwischen Styr und Bug: Bunte Blätter aus Wolhynien, Publisher: Zentralstelle der Feldbuchhandlungen, 1917. (Photos of Sokal during WW1).

- Further resource (not accessed): Diary of Eugen Hoeflich (Moscheh Ya'akov Ben-Gavriel).

- Sokal during WW2:

-

"Years of Horror - Glimpse of Hope",

by Moshe Maltz, Shengold Publishers, Inc., New York, (1993).

Diary, with the description of the Maltz family’s life in hiding in Sokal during WW2. -

No. 4 Street of Our Lady

No. 4 Street of Our Lady is a documentary about Francisca and Hela Halamajowa, two "Righteous Among the Nations" who hid 15 Jews from Sokal during WW2, directed by Judy Maltz, based on her grand-father's diary.

Watch it on Vimeo -

Two articles on the fate of Jews in Sokal during WW2 by Judy Maltz.

A Mystery Uncovered, 60 Years After the War

A Twinkle in My Grandfather's Eye - The story of Fran Fay Letzter Malkin, who hid for 18 months in Mrs. Halamajowa's barn.

- Rescue of a Antonia ("Tosca") Gruber , by Nestor Zenon Sniadanko. Obituary by Yossi Sarid. Link to Haaretz article.

- Sokal is also mentioned by Father Patrick Desbois in his book "The Holocaust By Bullets" - Pg.124-127. (Submitted by Fran Fay Letzter Malkin, daughter of Eli Letzter who was shot by the brick factory along with 400 victims.)

- The extraordinary story of Ralph Israel Charak, who survived the liquidation of the ghetto and escaped into the forests where he hid until the end of the war, as written by his grand-daughter Sarah.