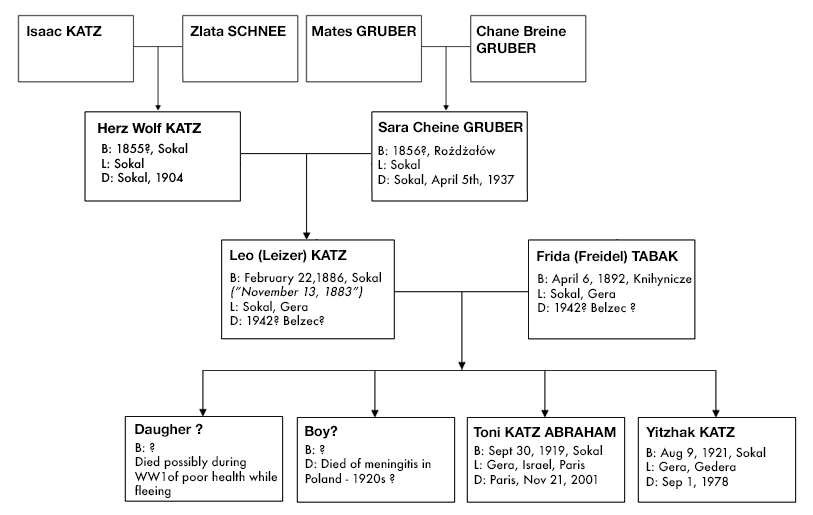

Leo and Frida KATZ

Hebrew name: Eliezer

Yiddish name: Leiser

Alternate spelling: Leyzer

Sokal

Leo (Leizer, Eliezer) Katz was born in Sokal to Herz Wolf Katz and Sara Cheine Gruber.

Sokal was a shtetl on the river Bug, in Eastern Galicia, whose population was over 40% Jewish up until the Holocaust. At the time of Leo's birth, Sokal was part of the Austro-Hungarian empire. It would become part of Poland after WW1. During WW2 it would be occupied by Russia, then invaded by Germany in 1941. It is now part of Ukraine.

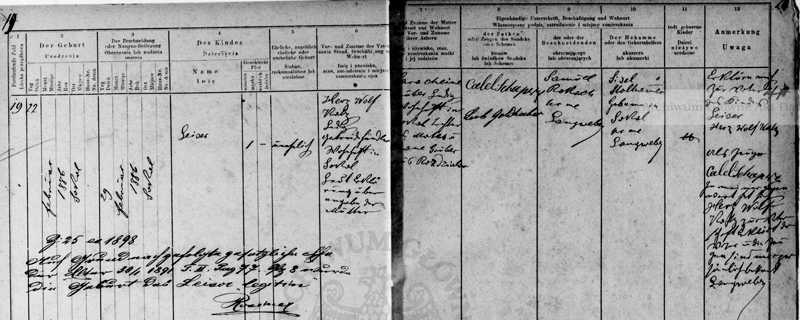

| Sokal PSA AGAD Births 1858-1905 | Deaths 1831-1905. Lwow Wojewodztwa / Ukraine (records in Fond 300 in AGAD Archive) Records from: agadd |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Given Name | Year | Type | Akta | Sygnatura | Sex | Father | Father Surname | Mother | Mother Surname | Mother Town |

| Leiser | 1886 | B(irth) | 19 | 1180 | M | Herz Wolf | KATZ | Sara Cheine | GRUBER | Rozdzalów |

Leiser Katz birth registry: February 1886

The date for Leo's birth is usually given as 13 November 1883, however the Sokal birth registry indicates 22 February 1886.

Leo's father Herz Wolf was a grain merchant, as evidenced by Leiser's birth record, where he was listed as "Getreidehändler" ("grain dealer").

This is what his granddaughter Toni recalled:

"Herz Wolf had a grain business and led a comfortable life. Leo originally worked for his father, but eventually decided he wanted a different life."

His great-granddaughter Eve Katz instead recalled:

"Aron's parents [Herz Wolf and Sara Cheine] ran a restaurant."

This seems however to have been Sara's profession, possibly after Herz Wolf's death. Indeed the marriage record for Leo's brother Nachman from 1919 show that Sara Gruber was then an innkeeper. The Sokal archives in Warsaw also contains a reference to a Katz who was an inn-keeper in Sokal at that time, however without more details.

Herz Wolf, Leo's father, died in 1904 at the age of 48 and, according to Eve Katz, "died of natural causes at a relatively early age, in his forties or fifties." His son Leiser was eighteen years old.

In 1911, Leo Married Frida Shulamit Tabak, from Knyaginichi (Knihynicze).

WW1

In 1914, Leo was drafted into the Imperial and Royal Army ("k.u.k. Armee") and fought - supposedly without much enthusiasm - for Kaiser Franz Joseph and the victory of the Central Powers.

The Russian soldiers invading Galicia were feared by the civilian populations, especially by the Jews who expected the worse from the Cossacks: pogroms, rapes and murder.

According to my mother, While Leo was fighting in the war, Frida, a young baby of hers who wouldn't survive, and Leo's mother Sarah, fled the advancing Russian [or Ukrainian?] army and managed to escape to Czechoslovakia. Leo had been declared "missing in action" - nobody knew where he was. Frida met a man she knew - also a soldier - in the train station, who told her that her husband was in the same town with his garrison. And so they were briefly reunited during the war.

According to my mother, Frida lost her first baby around that time. She said the infant had died of malnutrition, or had fallen sick - the result of the lack of medical care during their flight. Contemporary records - such as S. An-sky's "The Enemy at his Pleasure" - paint a vivid portrait of a terrorised, homeless refugee population fleeing from Galicia, with scores of children dying of cholera epidemics and malnutrition.

Polish-Russian war

1918-1919 After the end of the war and the Versailles Treaty which dismantled the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Poland became independent. Soon, despite its engagement to protect the rights of its minorities, the new nation became increasingly unwelcoming for Jews. Then, in 1919, the Polish-Soviet war broke out, bringing in its wake violence and destruction to Galicia's Jewish population.

More and more Jews started to emigrate - to America for those adventurous enough to travel across the ocean and uproot themselves more than 5 000 miles away, to Palestine for the very small minority who shared the Zionist dream, and for many others, to neighboring Germany.

For many Galician Jews, Germany represented progress, freedom, and an opportunity to build a better future for their children. Galician Jews were generally Germanophile: Austria had granted them equal rights, many of them had fought in the Austrian Army during the war, and as soldiers they had learned German and absorbed part of the German culture. According to Joseph Roth ("What I Saw: Reports from Berlin, 1920-1933", page 23), "50 thousand refugees came from the East to Germany after the war."

Fatefully, Leo chose Germany. He could have chosen America, which was still open to immigration until the Immigration Act of 1924 which would severly limit the number of immigrants through a national origins quota.

Not only was Germany much closer than the United States, but two of Leo's brothers - Aron and Mathes - had already moved to Gera, a mid-sized city in Eastern Germany. Combined with Leo's knowledge of the German language (and presumably ignorance of English), it seemed like the most logical choice. This decision would later turn out to have been a terrible mistake, eventually leading to the extermination camps in the East, but there were no inklings then of what was to be.

Leo's elder brother Mathes had been the first to come to Gera and lived there with his wife and daughter. His brother Aron and his family had followed in 1914. The two brothers had a business together selling goods on the installment plan "the same type of store that Jacob had later in Harlem" according to my mother.

Gera

And so, sometime in 1920 or 1921, Leo left Sokal and came to Gera to begin a new life. He left behind his wife Frida, his daughter Toni who was one or two years old, together with another child, who would die of meningitis a few years later. It is possible that his son Yitzhak was not born yet. The family would join him in Gera once he had established himself and could provide for the family.

At first, Leo worked with his brothers Aron and Mathes in their store in Gera. After a while, he was able to open his own store.

1921: Yitzhak, Leo and Frida's youngest child, was born 9 August 1921 in Sokal.

1922: Leo's family - Frida, Toni and Yitzhak - finally left Sokal and came to Gera around 1922. Toni was two or three years old and Yitzhak no more than one.

The only thing my mother remembered was that at the station in Gera, there was a man looking at the arrivals - her father. Her mother was carrying Yitzhak - he was still too young to walk. Later she was told that a woman from the Red Cross had helped them carry their luggages.

When asked if she had ever known Polish or if she had any memories of Sokal, Toni said she was too young when she had left Poland and didn't remember anything. As for her brother Yitzhak, who may have been as young as 6 months old, he certainly had no memories of Sokal. For them, German would be their mother tongue. As for Leo and Frida, they certainly would have had little nostalgia for a place from which they had fled. Years later, during Hitler's rule, when my grandfather had suggested that they should maybe leave Germany and return to Poland, Frieda would say she would never go back. Life under Hitler seemed a better choice than to go back to Sokal.

Like so many other Jews, they probably felt that they had finally arrived to a safe haven, ready to build a better life for themselves and their children.

They had left behind a third sibling with meningitis, in the care of another family. They would send money to this family every month to cover his care, and would learn much later that the child had long been dead, but the family didn't tell them and continued to take the money. It is not clear why they abandoned this child behind. Where there laws that prevented them from bringing sick people to Germany? Did they plan to bring the child at a later date?

I know very little about Leo and Frida's lives as my mother never talked about the past. I imagine however that what Max Frankel wrote about his grandfather, Leo's brother Mathes, also applied to our family.

"[Their] passports were Polish, not German, although neither spoke Polish and had not lived in Poland since early childhood. Actually, they never lived in "Poland" at all; [...] Their native village, proverbial shtetl named Sokal, [was a] dot on the map in a region called Galicia of what was then the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The region became Polish again after World War I, in 1919; it became Soviet at the start of World War II, in 1939, then German, then Soviet, and finally Ukrainian at the end of the Cold War, in 1991."

"The Katzes of Sokal migrated separately before World War I to the city of Gera in German Thuringia and took apartments in adjoining streets. They came in search of economic opportunity, which they found by buying and selling rags and cheap clothes, but they never lost the stigma of being Ostjuden, Eastern Jews. Even without the ethnic instruction of the Nazis, the German Jews looked down upon the scruffier ones from the East and not infrequently wondered aloud why they didn't go back where they came from. The Ostjuden looked too Jewish and talked too Jewish; they were embarrassing obstacles to the German Jews' "assimilation," which was an exercise more in hiding than in merging. The bent and bearded caricatures of Ostjuden that German Jews carried in their heads looked very much like the pictures the Nazis drew to portray all Jews everywhere."

"They thought of themselves as born in Austria-Hungary and only perversely branded Polish; they felt like Jews and lived like Germans. [...] "

Siegmund Spiegel, a friend of Toni and Yitzhak, recalled:

"In 1921, 1922, shortly after they arrived, at the very early stages, [the Katz family] lived for a very short time upstairs in a hotel, near the marketplace."

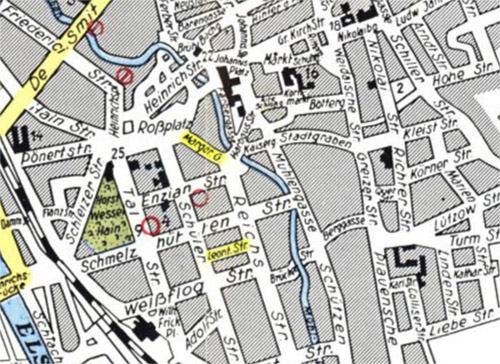

Their first apartment, where they would remain until 1938, was on Margarethengasse, 6. My mother described it as a "nice, middle class, comfortable four room apartment, with kitchen, bathroom, mansardes".

The Katz house on MargaretenGasse, Gera.

Map of Gera: Margaretengasse and Leontinenstrasse.

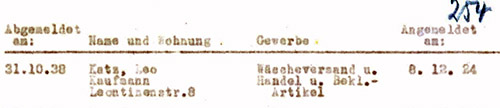

Leo Katz's addresses and store locations in Gera: 6 Margarentgasse, then 8 Leontinenstrasse.

Gebruder Katz

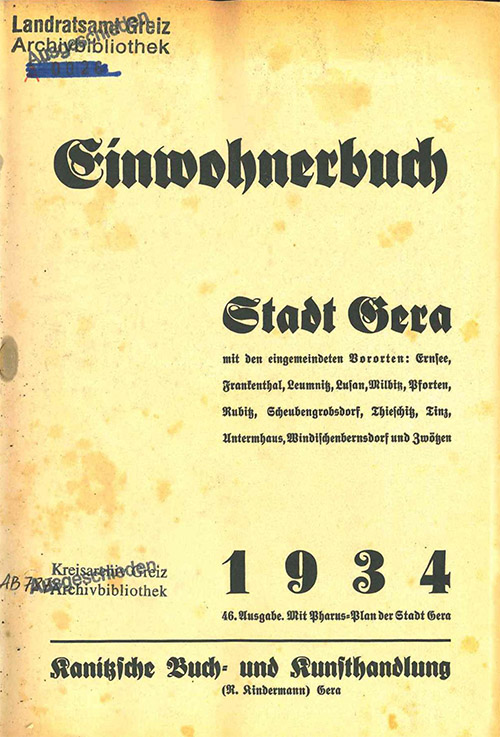

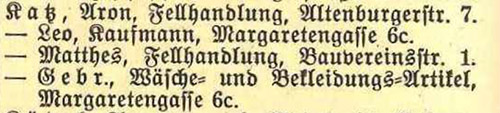

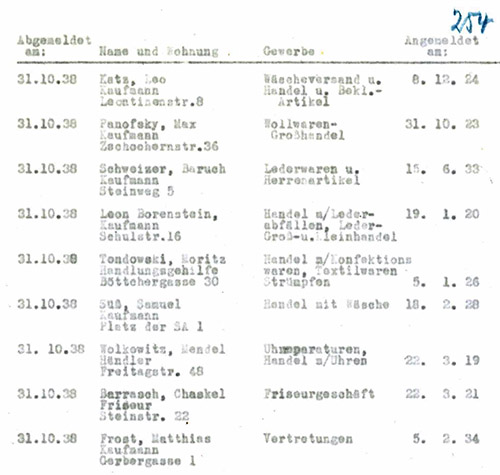

At the end of 1924, Leo and his brothers opened a shop together, with Leo acting as manager. The joint venture was registered under the name "Katz Brothers" ("Gebruder Katz OHG") on December 8, 1924. The store sold linen and clothing articles ("Wäscheversand und Handel, Bekleidungsartikel") and was located in 6c Margarengasse, on the ground floor of the building where Leo's family lived.

"Gebruder Katz OHG" was registered on December 8, 1924.

(The LeontinenStrasse address shown here is for the later location of the store before it was "deregistered" after the deportation to Poland in 1938)

(Gera City Archives)

According to Siegmund Spiegel, Leo and Frida's store on MargaretenGasse was in the front of the building, whith the family living upstairs. Although the street looks rather desolate on this photo, the neighborhood was probably quite nice. MargaretenGasse, situated between Roßplatz and the Mühlengasse, led to Roßplatz, which appears on all contemporary photos to have been a very nice, commercial area near the center of the city. The family lived at that address until 1937 or 1938. The street would be later be destroyed during the Allied bombings in 1945.

According to the 1938 "deregistration" of the business (more on this later), the business - Gebruder Katz OHG - was registered on December 8, 1924.

According to Werner Simsohn's book "Juden in Gera, vol II":

"[The three Katz brothers Aron, Leo and Mathes] ran a joint business for linen and clothing items at Margarethenstraße 60 under the company name 'Gebrüder Katz OHG', which was managed by Leo, who initially lived at the same address but later moved to Leontinenstraße 8. This business existed from December 12, 1924 to December 31, 1933."

According to Werner Simsohn, "Gebruder Katz OHG" ("Brothers Katz General Partnership") was a joint venture between the three Katz brothers, Aron, Leo and Mathes, with Leo the manager of the business. According to www.literaturland-thueringen.de however, the partnership was only between Mathes and Leo).

Again according to Simsohn, the business existed from December 12, 1924 to December 31, 1933. The December 1933 end date is obviously incorrect, since Leo's business existed until its "deregistration" on October 31, 1938. It seems however that the partnership ended, as Aron and Matthis registered a separate business on January 20, 1934.

Aron and Matthis both registered a new business on January 20, 1934.

(Gera City Archives)

Simsohn also states that Leo Katz registered a branch in Schmölln (15 miles east of Gera) in 1930, but that it would close within a year.

It was a small store that sold linens, underwear and all sorts of goods made out of fabric. The business afforded the Katz family a comfortable existence.

Siegmund Spiegel:

(Leo and Frida) were very honorable, very decent people, who worked hard to make a living in their store.

Like most Eastern European Jews at the time, they worked at the businesses where you had the part-time payment - customers paid on the installment plan, on credit.

Frida was a very energetic lady. She was a business woman. She worked... whereas he stayed to manage the store... They had a retail business, time-payments, and she went out collecting, too.

She went to collect, not him. He was somewhat a slow-moving person, and she was a very energetic lady. She was the tough one, yeah, certainly tougher than he was. He was more easygoing...

Leo and Frida worked hard to send Toni to school... She went to public schools for the first three years, but then went to MittelSchule, which cost money.

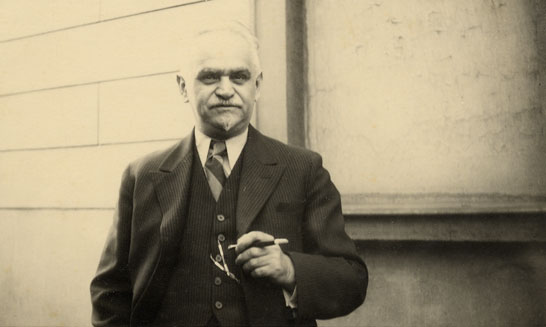

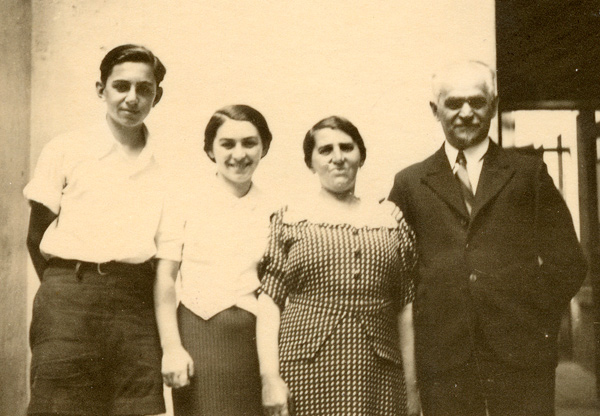

The earliest surviving document of the family is this photograph, taken in 1932 in the garden of one of their friends.

Yitzhak, Leo and Toni - Gera, 1932

Photos from this period show Leo wearing a three-piece suit with a gold watch chain, and with a cigarette holder - the image of middle-class success.

According to Siegmund Spiegel, "Leo Katz always smoked with cigarette holder".

(Photo courtesy of Shulik Mir)

At home, they spoke mostly German, and maybe some Yiddish. Their friends were mainly Galizianer Jews, and they had very little contact with German Jews, probably even less with non-Jewish Germans, aside from maybe interacting with neighbors. They went to the synagogue where Galician Jews went, while German Jews went to their own synagogue.

Leo and Frida kept a Jewish home: they kept Kosher, observed Shabbat, fasted on Yom kippur and celebrated the holidays.

According to Siegmund Spiegel, they were probably Social-Democrats, and Zionists, "like most Galician Jews." But, according to my mother, Leo said that, to go to Israel, you "either had to be very rich and be able to lose your money, or be poor and have nothing (to lose)". He didn't see aliyah as an option for them, although Frida seemed more sympathetic to the idea.

1934 Gera Einwohner Buch (Resident Directory)

(Gera City Archives)

1934 Gera Address Book: Margaretengasse 6c was the address where the family lived and the location of the store.

(Gera City Archives)

1933 to 1936

On 30 January 1933, Hitler came to power. After an initial boycott of Jewish stores on April 1, the Nazi regime passed a law on April 6 banning Jews from being teachers, judges or holding any government positions. A second law soon followed, barring Jews from being lawyers, doctors and notaries. That same month, German law now also restricted the number of Jewish students at German schools and universities.

In 1935, antisemitic propaganda increased, and on September 15, the Nuremberg Laws were passed, removing Jews from German society. Jews were no longer citizens and were now deprived of basic citizen rights.

Leo, Gera, 1930's.

Frau Kraft, Gertrud Knoll, Herr Kraft, Leo Katz. Gera, 1930's.

In 1975, Gertrud Plötner (widow Knoll) send Toni this photo along with the following explanations:

My husband (Rudy Knoll) took this picture. Sitting next to your father is Master Plumber Kraft (he lived Rossplatzgaesschen), then it's me (Gertrude Knoll) and next to me is Frau Kraft.

We sat together in the kitchen with a nice glass of grogg. Your father didn't drink any alcohol. Most likely, we brought up some apple juice for him from the basement. The photograph is from the '30s. We often sat together with your father.

My dear sister-in-law Lucie (born Knoll) also passed away. You knew her well, you used to go and visit the Knolls in Gera-Frankenthal.

This photo, and the last line ("you used to go and visit the Knolls...") suggests that there was indeed some form of socializing with "real" Germans, despite Siegmund Spiegel's statement to the contrary. Suprisingly, Leo looks like how he appears in the next photos below taken in 1936, suggesting that this photo may have been taken around the same time. This would make this socializing with German neighbors quite surprising, considering the pressure on Germans to shun Jews and stop interacting with them.

In 1936, Jews were banned from all professional jobs. Between 1937 and 1938, new laws were implemented, and the segregation of Jews from the "German Aryan" population was completed.

Leo, Frida, Yitzhak and Toni, Gera, October 1936.

Note the gold watch chain on Leo's vest, and Frieda's necklace. These will disappear on subsequent photos.

When the situation for Jews started to get really bad, Leo thought that maybe it would be better to go back to Poland after all, but Frida rejected the idea categorically, she would NEVER go back, she was terrified by the thought. No matter how bad things had become in Nazi Germany by then, Poland seemed to her a worse choice...

1937

Eventually, Leo and Frida couldn't keep their store anymore because of the anti-Jewish boycott and racial laws. They now conducted business from their home. They stored merchandise in their appartment, and customers came to their home. According to Werner Simsohn's book "Juden in Gera vol I", Leo was described as a "travelling salesman*" in 1937. It is possible, and even likely, that the family lost their store at an earlier date. [* The term "travelling salesman" may be a transcription error on Simsohn's part, as the last mention concerning Leo Katz in the Gera City Archives from November 1938 simply refers to him as a "merchant" ("Kaufmann").]

The family moved to 8, Leontinenstrasse, in a smaller, four-room apartment, which also served as the warehouse for their linen and ready-to-wear merchandise.

Leontinenstraße 8, today Karl-Schurz-Straße 8.

Photo courtesy of Christel Gäbler, Director of the Gera City Archives (2023).

Siegmund Spiegel:

"I think when they lost their business on MargaretenGasse, then they moved to Leontinenstrasse. That was already a smaller apartment, I think at that point, already, economically, things were not going too good..."

From that point on, they had to run their store from their apartment:

"You had a closet full of merchandise, and that's it! Because then most of the business was conducted, literally, going to your customers and - usually a house - and bringing stuff, peddling... It went back to peddling in a sense."

On April 5, 1937, Leo's mother, Sara Cheine, died, and Leo went to Sokal "to bury her", although this was probably a figure of speech, as she was buried the next day. This must have been quite a very strange and difficult trip for Leo, who travelled from Nazi Germany back to his childhood home, then came back to Gera.

In 1937, Leo and Frida's son Yitzhak left Germany and went to Palestine with Youth Aliyah, apparently against his parents' wish. Some time before his departure, the family posed for a series of photos, which Yitzhak would take with him to Palestine, thus preserving the only photographs that we have today of Leo and Frida.

Although specific information about such efforts is not available, there is no doubt that Leo and Frida, like most Jews in Nazi Germany, explored every possible way to flee Germany and deperately tried to get exit and emigration visas. In particular, they most likely reached out to Leo's brother Max who had come to the United States in 1913. My mother remembered her parents receiving a letter from her uncle from America, presumably about this quest - a letter important enough for her to remember it half a century later. Her friend Siegmund Spiegel later confirmed that the family seeked Max Katz's help, which he wouldn't - or couldn't - provide. (A postcard from Leo's nephew Saul Katz shows that Leo's brother Aron also asked his "American" brother in vain for help in securing a visa.)

Leo, Frida, Yitzhak and Toni. Gera, August 15, 1937.

(Photo courtesy of Shulik Mir)

Leo, Frida, Yitzhak and Toni. Gera, August 15, 1937.

Leo was apparently extremely affected by the departure of Yitzhak, and later said he would have been devastated if both kids had gone at the same time - he didn't know how he would have dealt with it. Frida seemed to deal better with it, "she was stronger". Leo however had not opposed the departure, saying that nobody knew what was going to happen, and he couldn't tell the children not to do it.

Note that on these 1937 photos, the gold watch has disappeared from Leo's vest; gone also are the necklace and earrings present on Frieda on the photos taken in 1936.

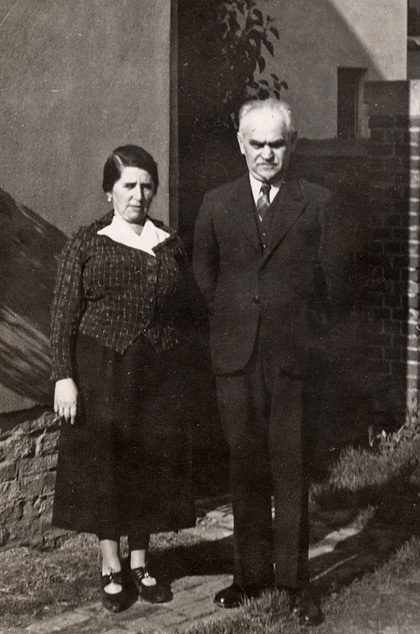

Leo and Frida, Gera, probably 1937.

By 1937, the government set out to impoverish Jews and remove them from the German economy by requiring them to register their property.

Even before the 1936 Olympic Games, the Nazi government had initiated the practice of "Aryanizing" Jewish businesses, meaning the dismissal of Jewish workers and managers of a company and/or the takeover of Jewish-owned businesses by non-Jewish Germans who bought them at bargain prices fixed by government or Nazi party officials.

1938

By January 1, 1938, German Jews were prohibited from operating businesses and trades, and from offering goods and services.

1938, October: Fearing a massive influx of Polish Jews from Nazi-annexed Austria, the Polish parliament had passed a law in March 1938 allowing for the possibility of revoking the citizenship of anyone who had lived outside the country for at least five years. On October 15th, a decree was published according to which only persons with a valid control stamp in their passports would be allowed into the country. The decree was to go into effect on October 30th.www.lbi.org

The Nazis did not want to "inherit" the soon-to-be stateless Polish Jews living in Germany, and a couple of days before the deadline, on October 28, 1938, they rounded 17 000 Polish Jews across all of Germany and deported them to Poland, during the so-called "Polenaktion".

Leo and Frida, together with Aron, Gusti, Saul, Mathes and Margule, were among those who were rounded up and deported that day.

In the early morning hours of Friday, October 28, 1938, around 140 Jews of Polish nationality living in Gera were rounded up without prior notice and were taken to the Ostvorstädter Gymnasium (Osterlandhalle - Eastern Suburban Gymnasium). [other source mentions "About 120 people: men, women, children had to wait in the bushes behind the Johanniskirche."]. From there, they had to walk to the main train station under guard and were forced to climb into Reichsbahn wagons, which were then locked. They were then transported from there via Leipzig to Bentschen (Zbąszyń) on the Polish border.

They were put on trains to Poland, and were allowed to take with them one suitcase per person and no more than 10 Marks. According to Hitler, since "Jews had come to Germany with nothing, they would leave with nothing."

With proverbial efficiency, and underscoring the seamless coordination between the various branches of the German machine, a clerk recorded on the following Monday, October 31, that Leo Katz' business had been "deregistered".

"Gebruder Katz OHG" was deregistered on October 31, 1939.

(Gera City Archives)

While her parents were beeing rounded up for deportation, Toni was in Hachshara in Flensburg in the north of Germany and - having been warned of the upcoming roundup - had managed to escape the fate of her parents.

When she finally came back home in Gera about two weeks later after Kristalnacht, she found an empty house. She said the expulsion had been so fast, there was still a cake in the oven that haden't finished baking...

Deportation to Poland

Whereas most Jews deported to Poland were kept in the Zbaszyn camp after their arrival, Leo and Frida managed to go to Kraków - either immediatly, or at least very soon after their arrival. My mother said:

"Most Jews went to a camp, but they were able to go to Kraków instead, because they probably had put some money aside".

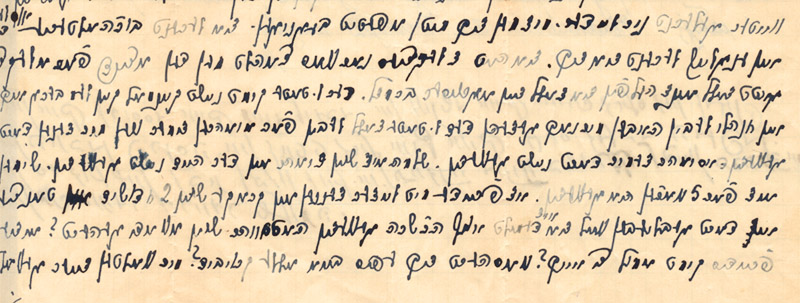

This is also confirmed by a letter sent to Aryeh Rebisch (Frida's cousin) by his sister in December 31, 1938:

Letter to Aryeh Rebisch, December 31, 1938.

"Freydl and Leyzer [Frida and Leo] have been in Krakow for two months.(*)[indecipherable name Tantse? Toni?] stayed there [DA: in Germany] because she was on Hachshara [...]"

They may have had some relatives in Kraków. Aron Katz' second wife, Gusti originally came from that city. Also, Max Frankel describes in his memoir how his family went to Kraków after their deportation from Germany, because his father had transferred some money there. Did the Katz brothers decide to stay togeter and help each other? Or was this their most logical destination?

While Mary Frankel and and her son Max would eventually manage to go back to Germany, then obtain exit visas for the USA, the rest of the family was now trapped in Poland, and would never be able to escape.

At first, Leo and Frida survived in Kraków with money their daughter Toni managed to send from Gera - money they had left with friends,"une cassette" [a lock box]. Toni also sent them some of their furniture and belongings - although only part of the what she sent them ever arrived.

Later Frida made "corsets, gloves, etc... That's how they survived... It was harder for men to adjust..."

While Max and Mary Frankel were in Kraków, Frida would sometime take care of him. According to Mary Frankel, one day they couldn't find Max and started to worry, until Frida came and said she had just taken Max to the movies because "it isn't good for a kid to be around grown-ups who worry all the time..."

German Invasion

On September 1, 1939, Germany invaded Poland, and that morning Krakow was bombed. On September 6, the German forces entered the city. Persecution of the Jewish population began soon after the German troops entered the city. In November 1939, all Jews 12 years or older were required to wear identifying armbands. In December the Germans carried out an extensive terror campaign in the Jewish neighborhoods of Kraków, aimed primarily at confiscating vast amounts of Jewish property.

In May 1940, the Nazi occupation authorities announced that Kraków should become the "cleanest" city in the General Government, and the Germans began expelling the Jews of Kraków to nearby towns. Of the more than 68,000 Jews in Kraków when the Germans invaded, only 15,000 workers and their families were permitted to remain, with all other Jews ordered out of the city, to be resettled into surrounding rural areas.

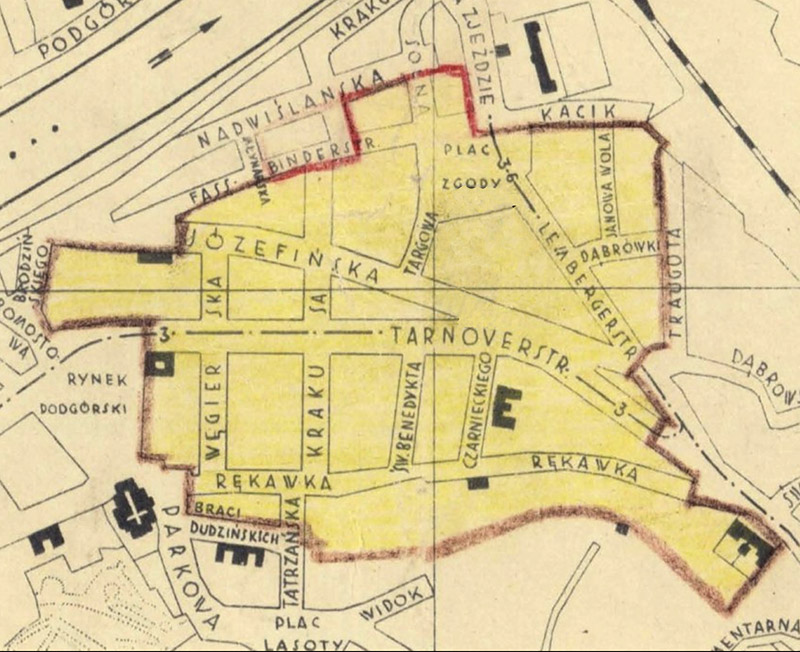

March 1941: Krakow Ghetto

In early March 1941, the Germans ordered the establishment of a ghetto, to be situated in Podgorze, located in the south of Krakow, rather than in Kazimierz, the traditional Jewish quarter of the city. This required that the non-Jewish population move out before the Jewish population could be forced in.

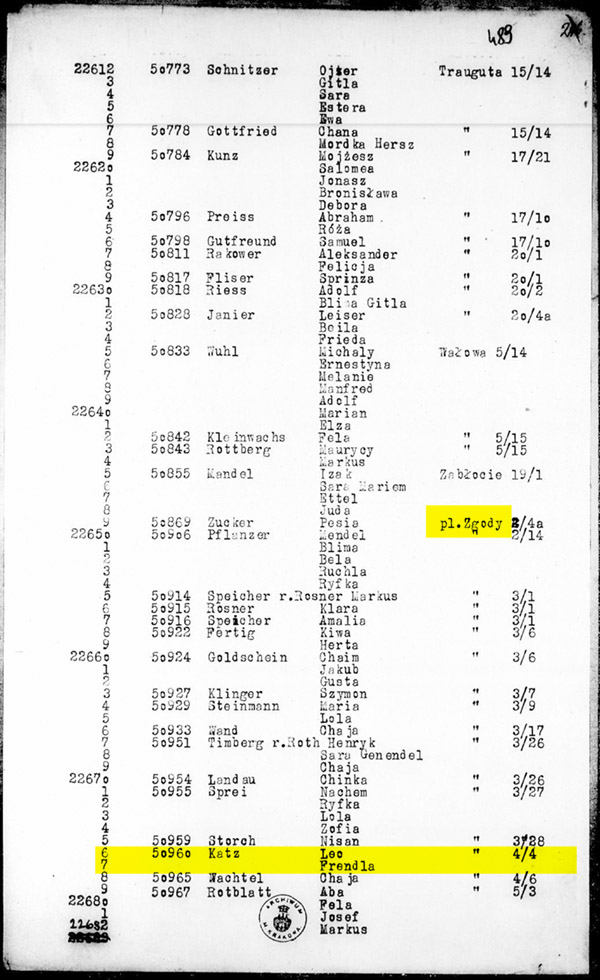

Leo and Frida's names appear on the Police Registration list of the Jews who were forced to move into the ghetto. Their address was Zgody Platz 4/4 - the main square of the ghetto. ("Plac Zgody", today: "Ghetto Heroes Square").

Police Registration list - Change of address, March 1941.

Last message, May 1942

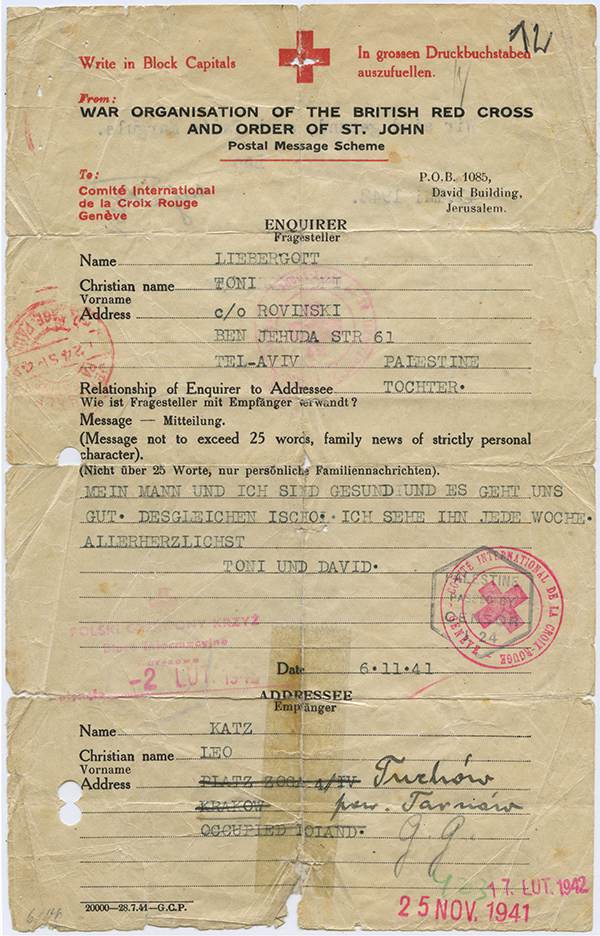

In early November 1941, their daughter Toni sent them a message from Tel-Aviv via the Red Cross.

The letter was sent to their address in Kraków - Zgody Platz 4/4. However, by the time the card arrived on November 25, 1941, Leo and Frida were not in Kraków anymore, and the card was forwarded to Tuchow, a small Polish town in Tarnow county, 55 miles (85 km) from Kraków.

The fact that the postcard was successfully forwarded to their new location indicates that someone in Kraków - either the German authorities, or the Judenrat - knew about their whereabouts, meaning that Leo and Frida were not in hiding, but had been relocated there.

It is impossible to know exactly when they left Krakow and arrived Tuchow. but it was probably sometime between April and November 1941, as they are not on the list of transports from Krakow for the period between 29 Nov 1940 and 2 April 1941, and Toni's card was rerouted on November 25, 1941.

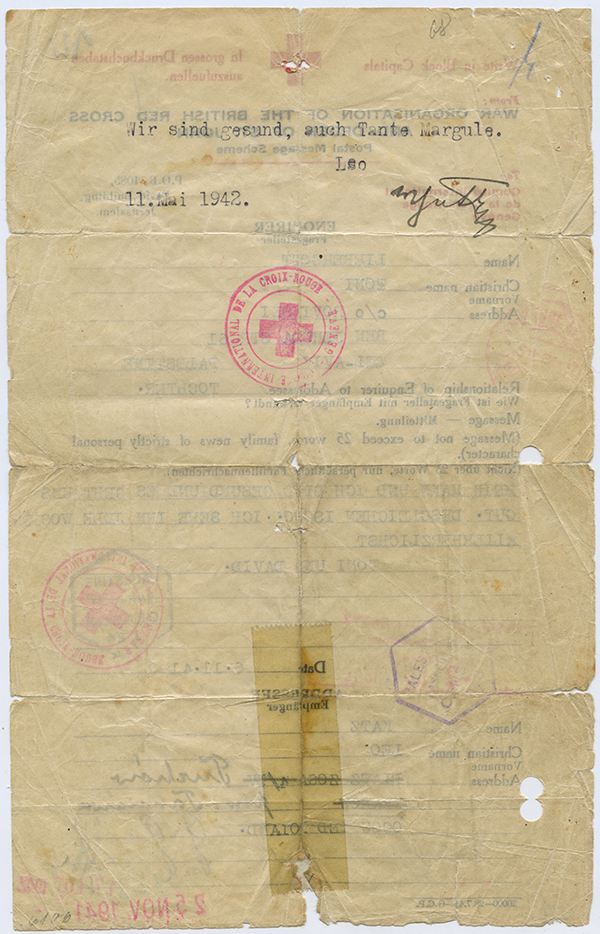

It took more than six months for this Red Cross card to finally reach its destination. However, the date of the reply (May 1942) is also surprising. The ghetto in Tuchow was established in June 1942, yet Leo and Frida were already in Tuchow in May of that year, if not earlier. Would the Germans have transferred Jews to another town without imprisoning them?

This would be the last message Toni would receive from her parents, six simple words:

May 11, 1942: "We are well, and so is aunt Margule".

The message was sent using a special International Red Cross form used to communicate between German-occupied territories and countries at war with Nazi Germany, such as Great Britain and its mandatory territory Eretz Israel. These letters only allowed for few words, and mostly one form of wording: "We are well,", "We hope you are also okay," and suchlike.

This was the last sign of life from Leo and Frida. Four months later, the Jews from Tuchow were deported to the Belzec death camp.

Red Cross Card, message from Toni, 6 November 1941

Red Cross Card, Leo's reply and last message, 11 May 1942

From: Toni Liebergot

c/o Rovinski

Ben Yehuda Str 61

Tel Aviv

PalestineTo: Leo Katz

Platz Zgody 4/IV

Kraków

Occupied Poland

Tuchow

By Tarnow

General GovernmentRelationship: Daughter

"My husband and I are in good health and doing well. So is Ischok [Yitzhak]. I see him every week

Love"

Toni and David"We are in good health, and so is Aunt Margule"

Leo.

Tuchow

The boundaries of the Tuchow ghetto encompassed 17 buildings in the southern section of the town. At the time of its establishment, additional deportees from the region were brought in, and the Jewish population reached 3,000.

At the end of the summer of 1942, the Germans ordered the Judenrat to conduct an exact census of all the residents of the ghetto. An "Aktion" took place in September 1942. The exact time of the "Aktion" is not known, but it was apparently prior to Rosh Hashanah of 5703. The ghetto was surrounded by the German and Polish police, and all of its residents were ordered to gather in the town square, where a selection took place.

Most Jews from Tuchow were deported to the Belzec death camp a few months later in September 1942.

Belzec

Unlike concentration camps like Auschwitz were Jews fit to work were spared to be used as slaves for a few months until they collapsed, Belzec was a "death factory". Its only function was to kill the daily human cargo brought in by train from the surrounding ghettos - several thousand Jews a day, every day. Victims arrived in the morning and were exterminated before the day was over, their bodies dumped into collective pits.

Only one (some say two) person is know to have successfully escaped from Belzec and survived the war. Between 500 000 and 600 000 Jews were killed during the 10 months Belzec operated. The camp was dismantled after less than a year of operation, its goal - the extermination of all the Jews from the region - accomplished. Trees were planted to hide the nature of the camp. After the camp was closed, Polish peasants from the area dug up the remains looking for "Jewish gold."

A monument was finally erected on the site in 2004.

Since many Jews from Kraków, and Jews from Sokal were also deported to Belzec (September 17 and October 28 1942), it is likely that most, if not all of the Katzes - those who still lived in Sokal, those who had stayed in Kraków, and those who went to Tuchow, all shared the same final destination.

Epilogue

After the war in 1945-1946, their son Yitzhak, who was stationed in Europe with the Jewish Brigade, would search for any trace of Leo and Frida, looking in lists of survivors and in Deplaced People camps, in vain.

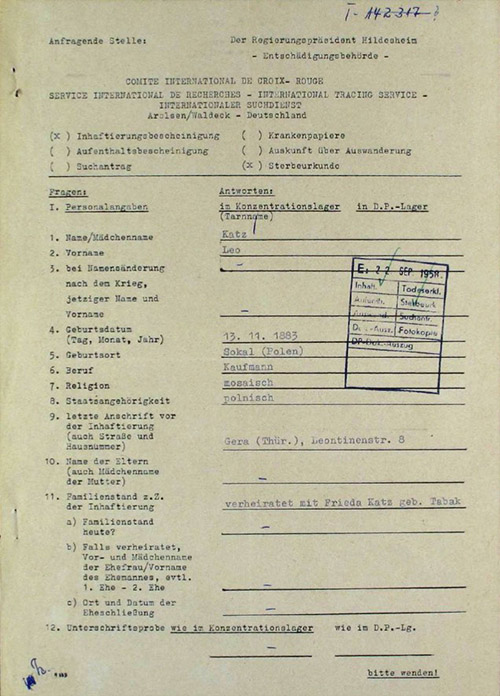

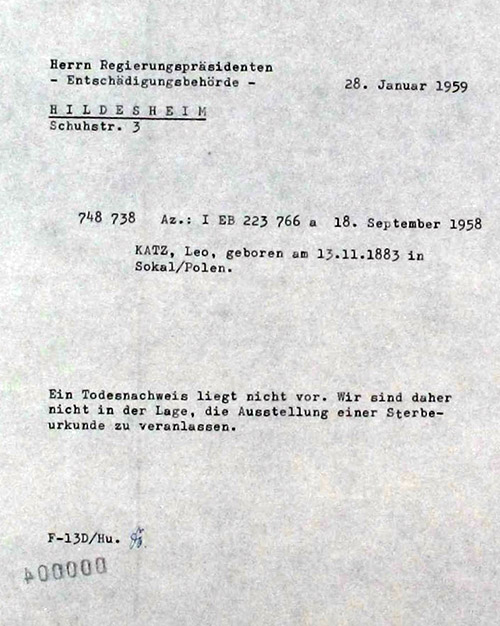

In September 1958, a search (?) for Leo and Frieda Katz was initiated via the International Tracing Service of the Red Cross in Hildesheim.

The response in January 1959 was a factual and bureaucratic exlanation: "There is no proof of death. We are therefore unable to arrange for a death certificate to be issued."

- Special Thanks:

- Shulik Mir, for sharing family photos

- Siegmund Spiegel, for sharing his memories of the Katz family in Gera.

- Ruthy Erez, for sharing correspondence to Aryeh Rebisch mentioning Leo's family.

- USHMM for providing a copy of the 1941 Krakow Police Registration file.

- I am especially grateful for Bernd Philipsen's effort in helping me recover the original copy of the Red Cross card from the Lower Saxony State Archives in Hannover (Niedersächsisches Landesarchiv Hannover).

- Christel Gäbler, Director of the Gera City Archives, for unearthing the registration records of the Katz brothers, the Gera Einwohnerbuch 1934 (Gera resident directory), and for photos of Leontinenstraße 8.

- Online Sources

- Interview with Siegmund Spiegel

- Police Registration list of the Jews who were forced to move into the ghetto

- www.literaturland-thueringen.de

- Wikipedia (Kraków Ghetto)

- mappingthelives.org (Leo)

- mappingthelives.org (Frida)

- Offline Sources

- Juden in Gera vol I. Publisher: Hartung-Gorre Verlag Konstanz (1997)

- Juden in Gera vol II. Publisher: Hartung-Gorre Verlag Konstanz (1998)

- Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka. Indiana University Press, 1999

- The Times of My Life and My Life with The Times. Random House, 1999

-

1920 Diary Isaac Babel.

Description of Sokal during the Polish-Russian war. -

The Enemy at this pleasure S. An-sky.

Description of Sokal during WW1 war.