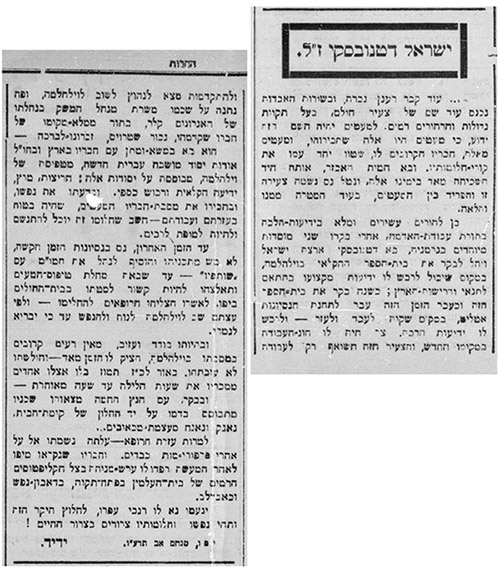

Israel Datnowsky

Name variations: Isrolke, Srolke

Until the discovery of a small collection of documents in the Central Zionist Archives in 2022, very little was known about Israel Datwnowsky's short life. Because he died a single man in his early twenties after living far from his family since the age of fourteen, most of what was known about him came from second-hand stories told by people too young to have known him, and from a handful of photos and postcards.

According to family lore, a quick summary of his life went something like this: Israel (Isrolke) Datnowsky was born in Latvia, the brother of my paternal grandmother. After his mother died, Israel and his sisters Ronya and Liska came to Constantinople. There, the sisters were set up with wealthy husbands, while Isrolke - the "black sheep" of the family who was "slow to learn" - was sent to Palestine. There he lived in the Templer agricultural colony of Wilhelma, near Jaffa. He died in 1916 from typhus, although the consensus in the family was that he might have met a more violent death, and had maybe been killed by a jealous husband.

While researching the story of the Aaronsohn family and their connection with my grandfather and his brother Haim Avraham, I uncovered two mentions about Israel Datnowsky, one in Aaron Aaronsohn's journal, and the other in a letter by Avshalom Feinberg, that offered a new twist on the circumstances of his death.

Then, in the spring of 2022, I unexpectedly found a trove of documents and photographs related to Israel in the Central Zionist Archives. These had miraculously been preserved after his death and had been sitting there for over a century, documents with absolutely no relevance or value to anyone, except to me and to a handful of distant relatives.

With these newly found documents, it is now be possible to begin to untangle facts from fiction and paint a more complete portrait of my great-uncle.

This page is a work in progress that will evolve over the next few months.

July 2022.

Early Life (1892-1906)

Israel (Isrolke) Datnowsky was born on July 24, 1892*, in Libau (Liepja), Latvia, the son of Abraham and Bassja Datnowsky. The only boy in the family, he had three sisters: Bertha, Ronya, and Liska (Eva), his twin.

* Note: the date is provided by the registration book of the Ahlem municipality, as uncovered by Marlis Buchholz.

Israel Datnowsky, 1897 or 1898

The Datnowsky family lived in Libau and Windau, and possibly Riga. The earliest picture of Israel Datnowsky is from a family photo taken in Windau around 1898.

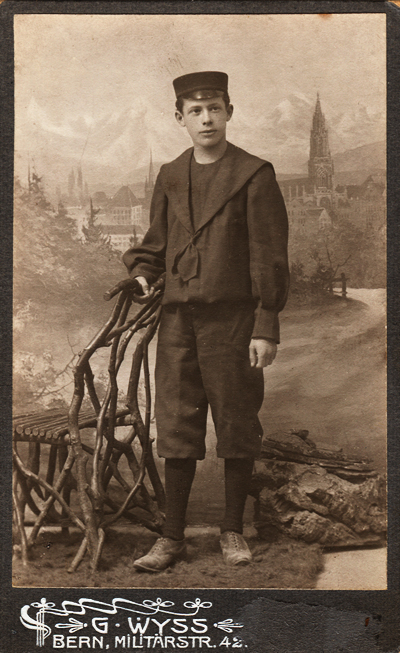

Israel Datnowsky in Bern, 1906*

The next photo of Isrolke was taken in Bern, where his elder sister, Bertha, attended the University starting in the winter of 1903 until possibly August 1906, suggesting that he came to visit her there. (* Although the date on the photo states it was taken in 1906, and it would coincidence with Bertha's stay there, he looks somewhat older than 14.)

Germany (1906-1911)

One of the few things that was said about Israel, albeit by people who hadn't known him, was that "he didn't learn". Suggesting that he indeed wasn't meant for studies, Israel was sent at the age of fourteen to a Jewish agricultural trade school in Ahlem, near Hannover, where he would spend the next three years.

According to the registration book of Ahlem, he arrived there in August 1906 from Charlottenburg where his elder sister Bertha and her husband Dr. Israel Auerbach lived. It is not known how long he was in Charlottenburg, but it was probably a short stay since the couple had only been married since December 1905.

Dr. Israel Auerbach, wrote to his sister-in-law Ronya after Isrolke's departure and mentioned how he had become "very close friends" with her brother.

Card from Dr. Israel Auerbach, addressed to Ronya in Windau.

Dear Ronja,

It's been ages since I wrote to you, hasn't it? I ask you not to be angry with me for this, I will certainly improve. I hope you are doing well.

How are you coping now without your brother? I became very close friends with Srolke when he was here.

I send my sincere regards to your esteemed parents.

Dr. Israel Auerbach

The Israelitische-Erziehungs-Anstalt zu Ahlem bei Hannover ("Israelite Educational Institution in Ahlem near Hannover") was a Jewish boarding school for horticulture and trades. The school had been founded in 1893 by Moritz Simon, a wealthy Jewish banker and philanthropist concerned with the social welfare of Jewish children from needy families. In New York, Simon had encountered the misery of poor Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe, and had concluded that the so-called "Jewish question" was a social issue, which required educating the younger generation to become artisans and farmers. He believed that "Our poor co-religionists can be helped not through charity, but through education to work."

The goal of the school was to provide vocational training in agriculture and handicraft to young needy Jews to improve their economic and social situation and make it easier for them to integrate in German society. An early prospectus authored by Simon described the institution as being intended for "orphaned, poor and uneducated Israelite children" from all parts of Germany. Its main objective was to instruct and promote "manual labor and factory work, handicrafts, agriculture, gardening and fruit growing among the Israelites on a larger scale".

The students were divided into two sections: pupils between six and fourteen years of age, and apprentices between fourteen and seventeen. I assume that Israel had completed his primary education in Libau, and joined Ahlem as an apprentice in the fall of 1907.

The apprentices had to sign on for three years, during which they were trained in various practical trades. Their apprenticeship covered horticulture and agriculture, including vegetables, fruit tree plantations, root crops, and cereals. The apprentices worked primarily in the gardens and in the fields and attended vocational training courses in the various branches of horticulture and agriculture. Besides agriculture, they also learned handicrafts: carpentry, shoemaking, bookbinding, baking, plumbing, etc. . Finally, in addition to this vocational training, they also received more general courses in regular subjects, such as German, arithmetic, geography, and religion - the school being under the supervision of the Hannover Rabbinate.

The main focus of the three years of apprenticeship in the Alhem agricultural school was on practical instruction, which was underpinned with theoretical lessons. The apprentice spent the three years of training successively in the three main departments: vegetable and agricultural department, flower and perennial department, and tree nursery and orchard. xxx

In the first year of apprenticeship, the apprentice began his training in the so-called vegetable department. Outdoor crops included: Red, white, green, savoy, flower and Brussels sprouts, various varieties of beans, peas, carrots, celery, kohlrabi, pumpkin, tomatoes, cucumbers and strawberries. The orchard included soft fruit bushes (blackberries, currants, gooseberries and raspberries) and fruit trees (apples, pears, plums, peaches, sweet and sour cherries). Finally, The agricultural sector included the cultivation of root crops and the cultivation of fodder and cereals on limited areas. In addition to potatoes for consumption on the boarding house farm, oats, corn, and alfalfa were grown as feed for the horses and chickens. xxx

The school atmosphere was "strict and disciplined". A contemporary inspector noted that "the order and attitude of the children is almost military, they are educated [...] to be punctual, regular and orderly." xxx

The students had a strictly regulated daily schedule, which began at 5 a.m. in summer and one hour later in winter. A former student who attend the school in the 1920's recalled: "Every day we were awakened at 6 a.m., at 6:15 a.m. there was a check - our bed had to be made, our shoes polished and our ears clean. There were also checks at noon and in the evening. At 6.30 we got breakfast - tea and bread - with jam. We never got coffee or fresh bread or white bread. [...] We only got meat on holidays. Once a week we had fish and on the other days we ate vegetables - potatoes, cabbage and so on." xxx

The same student noted that "The atmosphere in Ahlem was moderately religious. We prayed every day, with tefillin and tallit. On Mondays and Thursdays there were Bible readings in the dining hall. Before the meal we usually said the Birkat haMazon. On Saturdays we never worked. The food was kosher."xxx

Ahlem was a private welfare institution, funded by Moritz Simon along with several Jewish foundations and wealthy benefactors. In addition, individuals contributed smaller donations, including children's collections arranged by Jewish teachers all over Germany. Among the philantropic organizations paying for the education of impecunious pupils in Ahlem were several German lodges, including the Bnai Brith and Hanover Zion lodge. Other philantropic associations included France's Alliance Israélite Universelle (AIU) and the Jewish Colonization Association (JCA), which upported up to 18 apprentices in Ahlem until the beginning of the First World War.xxx

Whereas the yearly reports provide a detailed breakdown of all donations received during the year, there is no mention of tuition. Conditions for admission to the school are not known, which means that it's impossible to infer what the financial situation of the Datnowsky family was at the time. It seems puzzling that Israel could have attended a school for needy children, considering that his eldest sister Bertha had been enrolled (albeit briefly) in the University in Bern, his sister Liska had studied in Leipzig, while his sister Ronya attended the Russian gymnasium, which was also most likely a tuition-based institution.

In 1908, the school had a total of 140 students, 101 boys (44 pupils and 57 apprentices), and 39 girls (25 pupils and 14 housekeeping apprentices). Of the male apprentices, 37 (65%) came from Germany. The next largest group came from Russia, with 11 (19%) apprentices, a single one of them (Isrolke) from Libau.

The same year, the foundation reported that 192 assistants who had completed their training as apprentices since the opening of the program were employed. Of those, 179 were gardeners, the others having become cobblers, carpenters and bakers. Of the 179 gardeners, 72 were working in Germany, 32 in America, while only 4 (2%) were in Palestine: one was an "official of settlement cooperative", one was a manager, one a "colonist", while the last one was training to become an agricultural teacher.

These numbers illustrate that the goal of the Ahlem school was to prepare its apprentices for integration into German society. Unlike the hachshara movement that would appear in the 1920's, the Simon Foundation was not a Zionist enterprise and did not advocate for immigration to Palestine, nor did it offer courses related to the specific soil or conditions in Palestine. It is then surprising that Israel would later be one of the very few Ahlem student to immigrate to Palestine. (By 1932, the number of those who went to Palestine had risen, but was still only 8%.)

In February 1910, Israel left the school, as evidenced by correspondence from his classmates and from the director of the school. It's not clear if he graduated from Ahlem, or if he left before completing his three-year training. Maybe suggesting that his leaving Ahlem was a special occurence, forty classmates wrote to wish him good luck: "To our dear comrade: We wish Israel Datnowski the best of luck in moving to Steinhorst and every success in agriculture." The date of this letter (February 11) suggests that he left prematurely, as graduation was probably at the end of the school year in the spring or early summer.

From Ahlem, Israel went to Lehrgut Steinhorst, another Jewish agricultural and horticultural school in the Hannover region. The Steinhorst farming school was run by the same foundation which oversaw Ahlem, along with two other organizations - the Bodenkulturverein and the Hilfsverein der deutschen Juden. There, the students received an all-round agricultural training, from growing rye, wheat, barley, oats, beets, and potatoes, and animal husbandry (horses, cattle, and chicken). Steinhorst also boasted the most modern agricultural machinery. The institution's objective was the training and settlement of Jewish farmers, but it too was not a Zionist institution, and students were not encouraged to emigrate to Palestine, although a few of the graduates would eventually do so.

Israel Datnowsky spent at least one year in Steinhorst, as seven of his former classmates from Ahlem sent him a group photo on January 30, 1911, addressed to "Land und Lehrgutsgeselschaft Steinhorst bei Celle."

Souvenir from seven schoolmates from Ahlemn, 1911.

1: Gold, 2: Eyzyk, 3: A. Moch, 4: Scheinuk II, 5: W. Wollmann, 6: Scheinuk I, 7: E. Elkon

Source: Central Zionist Archives

Although there are no photos of Israel during his stay in the Ahlem horticultural school, it is easy to picture him with the same uniform during his years of apprenticeship.

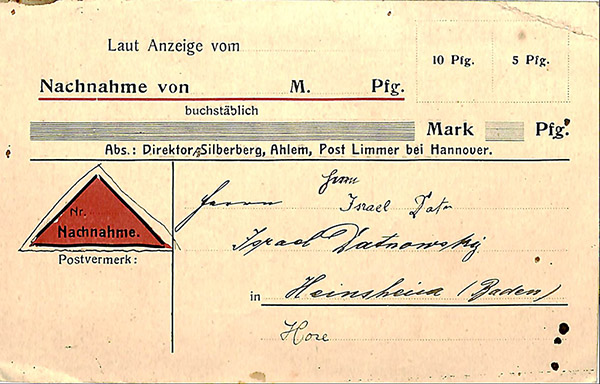

Israel did not remain in Steinhorst, as his 1911 membership card for the Association of Former Students from Ahlem listed his address as Heinsheim, Baden. Situated over 500kms away from Steihorst, Heinsheim is a small village with seemingly nothing that would have attracted him there; in particular, there was no agricultural school or training facility. With a population of just 1500 in 2022, and a Jewish community numbering just 80 in 1900, one can assume that Israel found work or an apprenticeship with a local farm.

Membership Card for the Association of Former Ahlemers for the year 1911

Addressed to Heinsheim (Baden)

Source: Central Zionist Archives, AK384/1-3t

Israel Datnowsky, date unknown.

Death of Israel's mother

Around 1909, Israel's mother Bassja died of cancer. Israel was about 16 years old. Following her death, his sisters Liska and Ronya came to Constantinople where they lived with their elder sister Bertha and her husband, Israel Auerbach.

Bertha later introduced her younger sisters to their future husbands - Ronya to Moritz Abraham, from Constantinople, and Liska to Asher Mallah, from Thessaloniki.

According to family lore, Israel also came to Constantinople with his sisters, and a pair of photos of the four siblings taken in the capital of the Ottoman Empire were inscribed - after the fact - as dating from 1909 or 1910.

From left to right: Israel, Bertha, Ronya and Liska in Constantinople, 1909*

Collection of the author

From left to right: Liska, Israel, Ronya and Bertha Datnowksy in Constantinople, 1910*

Collection of the author

It is quite likely, however, that these dates are incorrect, and that Israel didn't come to Constantinople until several years later. It appears that, despite the premature death of his mother, Israel continued to study in Germany between 1909 and 1911, first in Ahlem, then in Steinhorst. Another issue is that, in 1909, Israel was 17 years old, younger than he appears on these photos.

Unless Israel took a break from his training in Ahlem to visit his siblings, a more likely date for his visit would be between 1911 and 1912, when he could have stopped in Constantinople on his way from Germany to Palestine. Another possibility is that these photos date from the visit he made between May and June 1914.

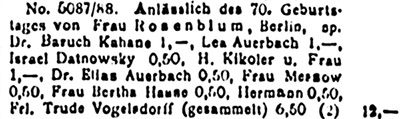

A notice in the February 5 1909 issue of the Jüdische Rundschau, the organ of the Zionist Association for Germany, shows that Israel contributed to a group donation for the Herzl Forest. A few other people who contributed on the same occasion - Dr. Baruch Kahane, Dr. Elias Auerbach, both living in Berlin then - suggest that Israel was probably there at the time, presumably visiting or on a break from school.

Palestine: Wilhelma

After completing his agricultural training in Germany, Israel came to Palestine. The exact date of his arrival is not known, but he was there by February 1912, as evidenced by a postcard from his sister Liska.

Why did Israel come to Palestine? According to family lore, it was said that, since he "wasn't very smart", "didn't learn" and "they didn't know what to do with him", the family had "decided to send him to Palestine." This however doesn't seem to be a convincing explanation, as, following his training in Germany, Israel would most likely have been able to find employment there, which would have been a much easier path for a young man than to become a settler in Palestine.

The vast majority of Jews who emigrated during the period of the Second Aliyah (1904 to 1914) settled in the United States, because of its greatest economic opportunity, while others settled in South America, Australia, and South Africa. Palestine on the other hand offered very limited economic incentives for new immigrants, and only a small fraction of Jews who migrated went to Palestine: between the years 1907-1914 almost 1.5 million Jews went through Ellis Island, while only about 20,000 immigrated to Palestine.

It is hard to imagine then that Israel would have come to Palestine without having some affinity for Zionism. It is not known however where and when he would have first encountered Zionism, wether in Ahlem or Steinhorst, or possibly later, after having met Israel Auerbach or one of the Abraham brothers in Constantinople.

In the winter of 1910/1911, his sister Ronya had traveled to Palestine, with a stop in Zichron Yaakov where she had met the agronomist Aaron Aaronsohn, presumably thanks to an introduction from her brother-in-law Israel Auerbach. Although not documented, it is possible that Israel traveled with her, and that the reason for the trip had been to explore opportunities for Israel's emigration one year later. This would also explain her visit to Aaronsohn.

Instead of moving to a Jewish settlement, Israel went to theTempler colony of Wilhelma (today, Bnei Atarot.) The Templers were Protestants from Germany who had settled in Palestine as early as 1866, believing that the second coming of Christ was imminent and that humanity's salvation lay in the gathering of God's people in a Christian community in the Holy Land. They believed that redemption could be achieved by hard work in the Land of Israel, and they aspired to a model of ideal living through forming productive farming communities. Their first agricultural colony was Sarona in 1871, while Wihelma was established in 1902.

Israel's presence in a Protestant settlement was seen as a mysterious oddity whenever my father mentioned Israel's story. There is however a logical explanation for this choice: the Wilhelma colony had opened an agricultural school in 1909, and Israel attended the Deutsche Ackerbauschule Wilhelma (Wilhelma Agricultural School).

Having been educated in Germany since the age of 14, and, as evidenced by his 1914 notebook, German was Israel's primary language. It then made the most sense for him to attend a German school where he could acquire further agricultural training, rather than one of the Jewish agricultural schools in Eretz Israel such as Mikveh Israel, where the main languages would have been Hebrew and French. As an added benefit, the Templers were known for using the most advanced agricultural practices in Palestine, having been the first to utilize chemical fertilizers, seed selection and farm machinery, arguably providing the best training one could have then in the region.

Although there are no earlier statistics, by 1922, Wilhelma had a population of 186 Christians, 36 Muslims and 1 Jew. Assuming that the numbers were not too different in 1912, on can imagine Israel's social isolation. Alone in an exotic land and possibly the only Jew in the Templer colony, he was 1800kms from his siblings and 4800kms from his father and hometown. It is not known if he had any friends or contacts when he first arrived, with the possible exception of Elias Auerbach, the brother of his brother-in-law, who had settled in Haifa in 1909.

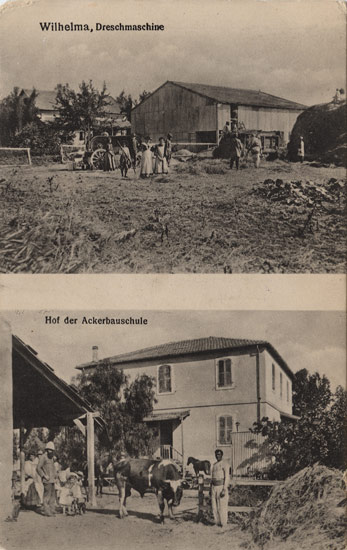

Two views of Wilhelma:

Top: Thresher

Bottom: Courtyard of the agricultural school

Collection of the author

In August 1912, Albert Silberberg, the director of the Ahlem school, wrote to Israel to thank him for having sent a report with his observations on agriculture in Palestine, which Silberberg planned to publish in the next issue of the Ahlem Association report.

It is not clear how long Israel remained in the agricultural school in Wilhelma, but about a year after his arrival, his situation had changed and he had taken on a new role. In January 1913, Albert Silberberg again wrote to Israel:

"I received your letter and I was very happy to see that you have now accepted a position that you like and in which you can still learn something, although I personally would have thought it more correct if you would have gone more into actual practice to gradually get to colonization. I can only say in general that someone who, like you, has enjoyed thorough practical training and good further training, best uses the knowledge thus acquired in practice and gathers as much experience as possible through it, in order to finally work on his own land to start a healthy existence.

[...] But I don't know enough about the conditions there to be able to judge in this special case whether it would be more advantageous for you to strive for the goal described above or to start studying again. [...] Let us hope that the effort, time, and expense that studying requires will be worthwhile."

It is not clear what this "new post" was as Israel's letters have not survived. One possibility is that, having completed his training in Wilhelma, Israel went to the experimental station in Atlit to receive additional training.

1914 - Atlit

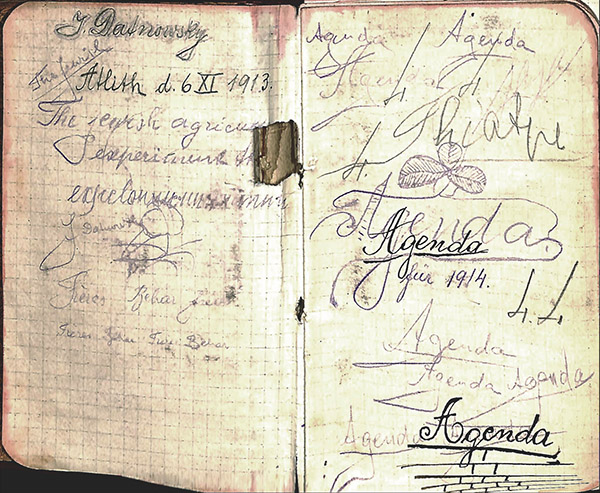

After attending the agricultural school in Wilhelma, Israel Datnowsky went to the experimental station in Atlit. The exact timelines and specific details about his role there are unknown, however Israel's notebook and a handful of letters provide some clues about his stay there.

The earliest hint can be found in Israel's notebook, which was preserved, along with a handful of letters, in the Central Zionist Archives. On the very first page, Israel wrote "Atlith 6 November 1913. The Jewish agriculture experiment [station]". This may have been the date when he first arrived there, although it is possible that he had been there as early as January 1913, when Albert Silberberg had mentioned the "new position" where Datnowsky could "still learn something".

In December 1913, Israel Auerbach wrote to Datnowsky a letter that points to his presence in Atlit. Although this is not specified anywhere in the letter, some of its content provide hints. Auerbach ended his letter with: "Best wishes to Messrs. Aaronsohn and Behrman", two names associated with Atlit. Aaronsohn headed the Atlit agricultural station, while Behrman was most likely Moshe Behrman, the former director of the Kinneret Farm, who was by then working with Aharonson in Atlit. A second hint, this one more circumstantial, is Israel Auerbach's conclusion: "Many greetings to Eli and his wife, as well as [...] Zeruja and [...] Daniel.". "Eli" was his brother Eliahu Auerbach who had opened the first Jewish hospital in Haifa, indicating that Datnowsky was in contact with him, and reinforcing the likelihood that he was then in Atlit, since Haifa is merely 10 or 12 miles away.

In his letter, Auerbach questioned Datnowsky's "strange haste to become self-employed, even though you are only 21 years old", implying that he should continue to be in Atlit (or maybe Wilhelma), instead of striking on his own. He added: "There is much that is reasonable in [your letter], even if there are some dreams beside it, e.g. that [your] dad should take part in the economic management of your 'future economy' and the suchlike. In any case, be certain that we will now study the matter seriously here and make a decision." This seems to indicate that Datnowsky was looking to strike on his own, and was looking for financial help from his family to help realize his dream. It also suggests that the family - more specifically his brother-in-laws - were considering how to help him achieve his goal. (About a year later, Haim Abraham, the well-to-do brother of one of his brother-in-law, would be corresponding with Aaronsohn about purchasing farmland in Palestine. Although it may have been just a coincidence, it is also possible that Haim's exploration would have been related to Israel's desire to establish his own agricultural exploitation.)

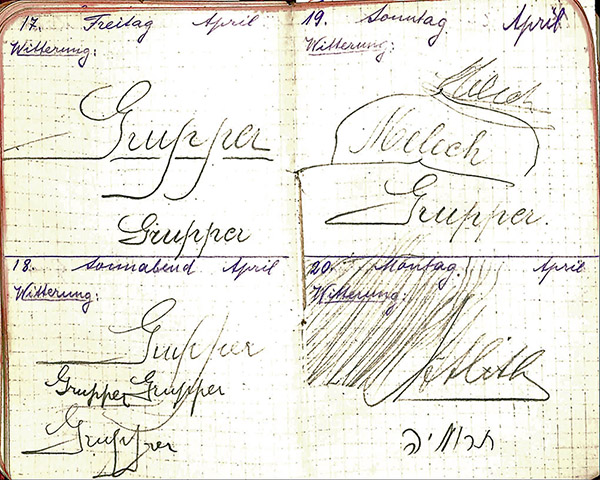

Starting in January 1914, Israel began keeping track of his daily activities in his notebook. From some of the names and events jotted down there, we can infer that he was in Atlit, af least for a significant part of 1914. Possibly conflicting with this conclusion, however, are several work-related entries on Shabbat, which would suggest a non-Jewish environment (i.e. Whilhelma). There is thus some uncertainty about where he lived during that year, with a possibility that he alternated between Atlit and Wilhelma.

Examples of entries include:

Thursday January 1 1914:

Oats sown for green fodder, marked out fields for carob and fig planting

Friday January 2 1914:

Artichokes transplanted on rigoltem soil, marked out fields for carob planting

Saturday January 3 1914:

Tree pits [...] (2.5p/per piece)

Sunday January 4 1914:

Fixed wind turbine, marked out fields for carob planting, dug tree pits

Sunday January 19 1914:

Repaired wind motor, dug tree trench, [...]

Sunday January 25

Laid out drainage ditch, dug pits, [...]

Wednesday January 28

Cleared the swamps on the western border, [...]

A wide range of crops and field work are mentioned in the notebook, indicating that Israel had the opportunity to expand his practical experience, although it's not clear what his role was - whether he was doing the actual work in the fields himself, or overseeing laborers. The list of crops includes oats, wheat, barley, alfalfa, cotton, onions, artichoke, almond trees, mulberry trees, acacia trees, poplars, figs, Washingtonia and Phoenix palms. (Washingtonia palms were imported in Palestine by Aaron Aaronsohn and first planted near Atlit in 1912.) Work activities include plowing, weeding, transplanting, tree pruning, grafting, and digging holes for trees. Other more mechanical tasks include repairing a wind turbine, laying out a drainage ditch or clearing out swamps.

Unfortunately, the notebook consists mainly of the daily weather, work-related notes, expenses, names, and contains very little personal insights. One rare occurence on Saturday February 14, Israel notes "No work during the day. Quite amused in the evening"

There are numerous gaps in the his notebook, during which he didn't note any work activities or weather statistics, suggesting that he may have been traveling or maybe alternating between Wilhelma and Atlit. From February 16 to February 26, the notebook pages are blank, maybe suggesting that he was not working temporarily. He was however still in Atlit, as on February 27, Israel noted "Visit from Mr. Rosenwald et Madame." Julius Rosenwald was the head of the Sear, Roebuck & Co. of Chicago. A noted philanthropist, he was reputedly one of the richest Jews in the United States. Although opposed to Zionism, he was a friend of Aaron Aaronsohn and a member of the board of directors of the Agricultural Experiment Station at Atlit, which he supported financially. He visited Palestine between February and March of 1914 and spent time at the agricultural station in Atlit. It is said that "Both of them were treated as visiting 'nobility' by the local settlers, who welcomed them with fireworks and singing."

On March 31st, Haim Abraham and Sarah Aaronsohn were married on the grounds of the Atlit station. I assume that Israel was present for the wedding of his relative - Haim was the brother of his brother-in-law, Moritz Abraham - however there are not entries mentioning the event.

Israel wrote almost exclusively in German, with a few, isolated exceptions where he put down single words in Hebrew, such as "Pessah", suggesting that, while knowning the Hebrew alphabet, he was not comfortable with the language.

Another occurence of Hebrew is an entry from April 20. There, Israel wrote "Athlit" and "תרומיה" ("Turumiah"), the Hebrew name of the settlement. The name, derived from Book of Ezekiel, 18:12: "And they had a contribution from the land's contribution" had been suggested to the colony by rabbis, but the name was short-lived, the settlement reverting to the name Atlit.

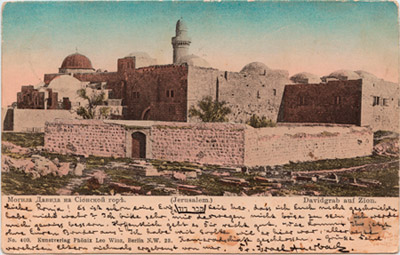

In early May 1914, several entries in his notebook suggest that Israel traveled. On May 8, he itemized the cost for "place to sleep, cap, belt repair, socks, souvenir". The next day, another itemized list of expenses included: "cap, suspenders, oranges, souvenir". On the following pages, yet another list: "ticket, toothbrush, embark, disembark, breakfast, ticket (a second time)", and on the next page: "breakfast, horse, lodging (?), ride to Jerusalem". On May 10, "Tel Aviv, ride (city)", and a word in Hebrew "חגיגה": "celebration". It is likely that the souvenirs Israel bought were not for him, but presents he would bring to his siblings in Constantinople later that month. Finally, one name: "Frank", which could refer to Henri Frank, one of the directors of ICA (The Jewish Colonization Association) and an official of Baron de Rothschild's administration, or to Itzhak Frank, a landowner mentioned by Aaron Aaronsohn in his letter to Haim Abraham in July 1914 concerning a potential sale of his property to Haim.

It is possible that Israel traveled from Atlit to Haifa, where he then took a steamer to Jaffa, which was, according to Arthur Ruppin's memoirs from the period, a better way to travel than by coach. ("The journey by coach from Jaffa to Haifa took one-and-a-half days. [...] The best connection between Jaffa and Haifa was by boat. Steamers made the voyage in no more than four to five hours."). From there he would have used a horse to go to Jerusalem, then to Tel Aviv.

On May 11, 1914, he noted "Mr. Franz Littauer, Berlin. Committee for Palestine Migration, Berlin W.15 Bleibtreustraße 25" . On the next page, another address: "Zionist Central Office, Berlin W.15, Sächsiche Strasse 8" (Franz Littauer was a young man from Berlin, born the same year as Israel. A member of the "Blau-Weiss" Zionist youth organization, he visited Palestine in 1914 while still a student, and decided to settle there after the completion of his training. After settling in Palestine he would later work as a Senior Plant Pathologist.) This entry suggests that Israel may have been looking to connect with German Zionist organizations, possibly to look for support for his plan of striking on his own.

Constantinople

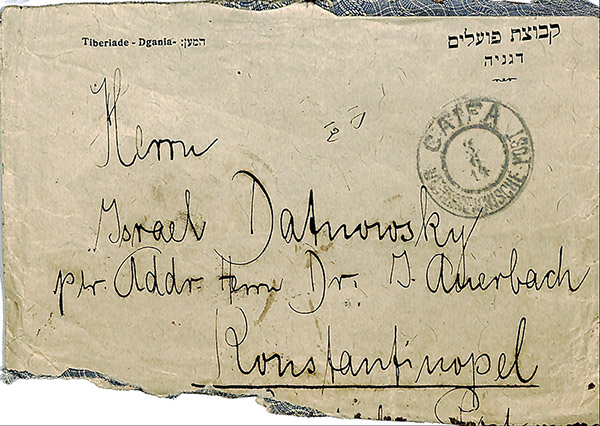

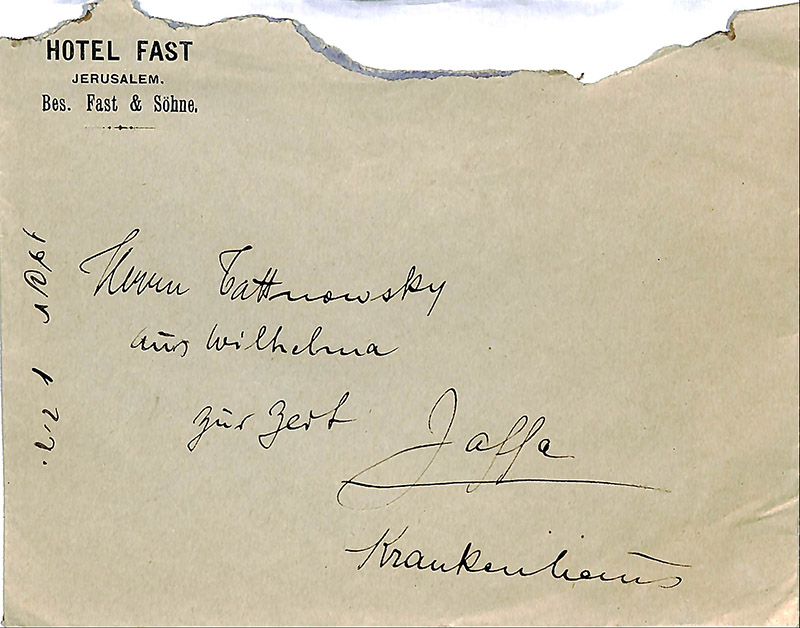

From May 18 up to mid-August, Israel's notebook is blank, thus providing no details about his activities over the next three months. A clue as to Israel's whereabouts is provided by a letter dated May 28 from Albert Lehman, a former friend from Ahlem. Surprisingly, the letter was addressed to him in Constantinople, c/o Dr. Auerbach.

Letter from Albert Lehman to Israel Datnowsky in Constantinople, May 1914

Source: Central Zionist Archives, AK384/1-3t

This suggests that Israel traveled to Constantinople sometimes in mid-May, where he would have reunited with his sisters and met his brothers-in-law. It is conceivable that the purpose of this trip was not vacations but to look for financial support for the venture that Israel Auerbach had alluded to in his letter six months earlier.

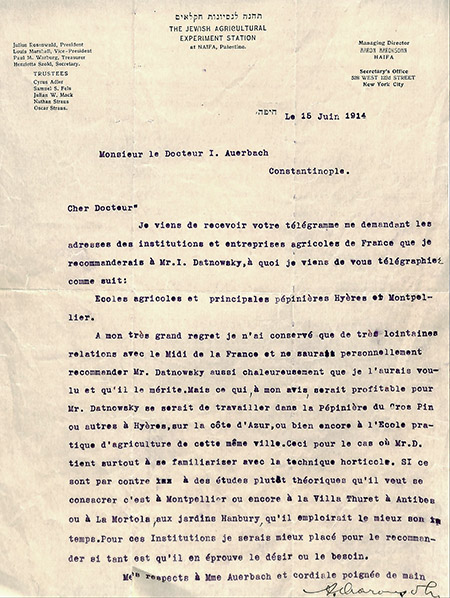

The next chronological artifact is a letter dated June 15, 1914, from Aaron Aaronsohn to Israel Auerbach, responding to a request for recommendations for Datnowsky.

Letter from Aaron Aaronsohn to Israel Auerbach in Constantinople, June 1914.

Source: Central Zionist Archives, AK384/1-3t

From this letter, it appears that Israel Auerbach had asked Aaronsohn if he could offer a recommendation for an agricultural institution in France for Datnowsky, suggesting that he was planning to further his studies, unless this was an idea pushed by the family before they would allow him to make the jump to becoming self-employed.

The tone of the letter suggests that Aaronsohn was not close to Israel Datnowsky, whom he refers to rather formally as "Mr. I. Datnowsky", despite the months Datnowsky had spent in Atlit.

The fact that studying in France was contemplated suggests that the family - his father, siblings or in-laws - were prepared to support him and pay for his studies. It also implies that Israel knew enough French to attend a specialized school in France, somewhat contradicting the notion that he "didn't learn". This would mean that he spoke Russian, German and French, in addition to Yiddish and maybe by then some Hebrew. An undated envelope from the renowned Montpellier Agricultural school addressed to Auerbach suggests that the family did consider sending Israel to further his studies there. In the end, Israel would not go, prossibly because of the onset of WW1 a month later on July 28, 1914.

From Aaronsohn's letter, we may assume that Datnowsky was in Constantinople at least until the end of June - when this letter would have arrived - as it was addressed to Auerbach.

Back in Atlit

It is not clear when Israel left Constantinople and made his way back to Palestine, as his notebook is mostly blank between mid-May and early October. An entry on October 4, 1914, listing the names of Atlit residents ("Loubanow, Lagrosa, Atlith"), shows that he had returned to Atlit by then. Because of this gap, we cannot know if he returned after the beginning of the hostilities, or earlier in the summer, also whether he returned to Palestine because the war had forced him to change his plans to study in France.

The remaining notebook entries from October 1914 to mid-January 1915 suggest that Israel was back in Atlit. Some of the entries consist of names of people associated with Atlit, such as Davidesco, Grupper, Lubanow, Aaronsohn. Additionally, a couple of entries with French terms such as "Blé d'Atlith", "Avoine jaune géante" (= yellow oats), "Seigle de Mars ordinaire" (Ordinary March Rye), "Aubergine" (eggplant) point to his being in Atlit, since Aaronsohn utilized French predominantly, as opposed to Wilhelma, which was a German colony.

Starting in late November, Israel's journal contains several lists of Arabic names, presumably groups of field laborers. Since both the Atlit settlement and Wilhelma relied on Arab laborers, these lists don't help clarify where he was during that time. The lists do suggest however that Israel was now working as a field manager.

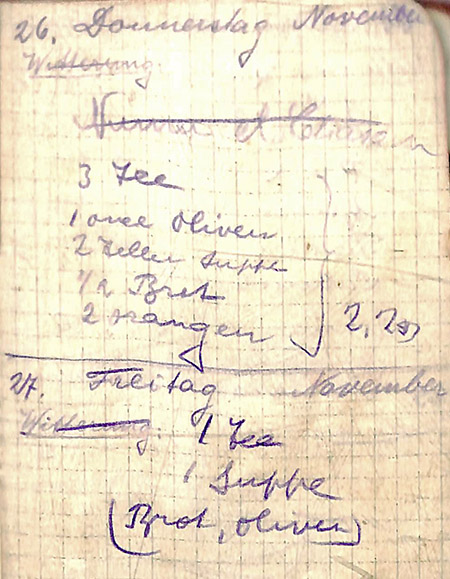

Several entries in the last months of 1914 detail meal expenses and suggest that his meals were rather spartan, mainly consisting of tea, soup, bread and olives, with the occasional addition of sardines and oranges.

Meal entries, November 1914

November 26: "3 teas, olives, 2 servings of soup, 1/2 bread, 2 oranges"

November 27: "1 tea, 1 soup, (bread, olives)"

Source: Central Zionist Archives, AK384/1-3t

One of the last entries from the notebook, undated but written after January 22, includes what looks like a packing list: "Breeches, khaki suit, spats, socks, glasses, suitcase [...]". Indeed, Israel would leave Atlit and return to Wilhelma at the end of the month.

1915 - Back in Wilhelma

At the end of January 1915, Israel left Atlit and returned to Wilhelma, as evidenced by a letter from his sister Ronya:

February 1, 1915

Dear Srolke!

We're incredibly surprised that we haven't received any news from you yet. Have you spoken to Mr. Löwy*, and how are things going with your affairs?

[...] Do you have any news from Bertha* and Liska**? (*Bertha, his eldest sister, was in Berlin wih her daughter Lea. **Liska, his twin sister, had gone to Salonika to marry Ascher Mallah).

So now if you want to write to papa, send the letter to Liska, and she will then send it to papa - do it absolutely so that he should at least have some news about the children at Easter, now that he is like that [he] is alone. I'll do the same - I'll also send him some money [?] for the holidays - so that he should have at least for Passover. He's completely cut off from Bertha*. [*Because of the war there were no more communications possible between Germany and Latvia, which was part of the Russian Empire.]

Bertha and Israel are supposed to be here for Easter*. God grant. [* This would not come to be; Bertha was unable to return to Constantinople for the entire duration of the war in Berlin.]

[...] Where and with whom will you spend Easter? For Easter I am sending you a small package - first with a couple of sweets from Liska's wedding, and, secondly, 6 pairs of new stockings, a couple of cravats, your piece of linen [?], 2 hand towels, and your napkin ring, and a few more small items [?]. But first of all I have to have news from you.

[...] How are you? I hope that you are happy and satisfied with your position. [...]

We're fine. How good it can be now. Everything is quiet here. [...] What is [happening] in Palestine? What is the mood? The groceries have risen quite a bit here, then nothing.

The weather here was the best until today, it's been snowing since this morning. How is Palestine? I hope you're not missing anything.

We are impatiently awaiting detailed answers to our letters as well as to Mr. Leroi's rejection. [?]

So - do not be lazy and write.

Best wishes to you from your loving sister Ronya.You promised to write to us often and in detail and also to send views from Wilhelma.

*Joseph Loewy (1885-1948), an engineer and Zionist entrepreneur was one of the pioneer German Jewish immigrants to Eretz Israel. He helped develop the Haifa Bay and was a founder of Nahariya. From 1913 to 1915, he worked in the Palestine Office in Jaffa, under the leadership of Arthur Ruppin, where he headed the "Technical Department". He founded various private colonization companies that bought up vacant land from Arab landowners and sold it to new settlers with equity through "amelioration" and parcelling for agricultural processing. Joseph Loewy was one of the best-known private investors in Palestine and the new state of Israel. I assume that Israel would have been in contact with him in regards to the potential purchase of a parcel of land. In July 1915, Loewy would visit Moritz Abraham in Constantinople and give the family news about Israel's work.

**Leroi: It is not clear who this Mr. Leroi was. Based on the French-sounding name, he may have been related to the Montpellier Agricultural School, or else could have been a member of the Rothschild administration in Palestine.

Maybe in response to Ronya's request, Israel mailed this postcard from Wilhelma on April 4, 1915:

"Plowmen in Kfar Uria". Postcard sent from Wilhelma, April 4, 1915.

Collection of the author

Wilhelma, April 4.

Dear all!

You have probably received my letter. I am doing very well, and I hope to hear the same from you as well.

I have written to Liska, Papa and Bertha as well. Here everything is uneventful as usual.

How were your holidays? I am looking forward to hear from you soon.

Best wishes

Israel

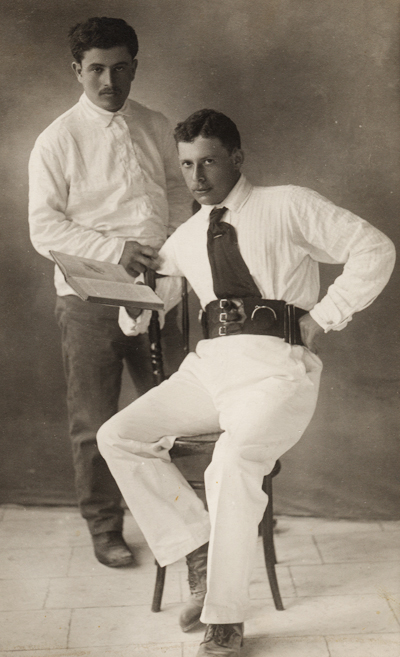

Israel Datnowsky with friend, Palestine, 1915

Collection of the author

In Wilhelma, Israel was now employed as a farm manager.

For Israel, working as farm manager in the Templer colony seems to have been just a temporary position, a mere stepping stone towards his dream of setting up his own agricultural exploitation. In parallel to his responsibilities a farm manager, he continued to look for an appropriate plot of land and for the required financing.

Although specifics are lacking, letters from his family dating from December 1913 to July 1915, along with his obituary, provide a several hints about his plans.

This had been the dream he had been exploring for over a year. As early as December 1913, his brother-in-law had mentioned his "strange haste to become self-employed".

His goal, as described in his obituary, was to start a new Moshava with a few friends, a settlement consisting of privately owned farms.

To realize his dream, he most likely appealed to his family to get the required financing, as hinted in Auerbach's December 1913 letter, who had said "we will now study the matter seriously here and make a decision". He may have also tried to get help from Zionist institutions abroad, such as the Zionist Central Office in Berlin.

A couple of names mentioned in his planner and correspondance refer to people who were involved in selling agricultural land to settlers. One, a Mr. "Frank", was possibly Itzhak Frank, a landowner mentioned by Aaron Aaronsohn in his letter to Haim Abraham in July 1914 concerning a potential sale of his property to Haim. Another person involved in lang sales was Joseph Loewy, mentioned in Ronya's letter to Israel in Ferbruary 1915 and Moritz's July 1915 letter.

It is likely that one of the goals of his trip in Constantinople in the spring/summer of 1914, was to get the financing he needed from his family. Around this time, Haim Abraham, the brother of his brother-in-law, was in contact with Aaron Aaronsohn about purchasing agricultural land in Palestine. Since Haim had no background in farming and doesn't seem to have planned to abandon his business and emigrate to Palestine at such an early date, it is very conceivable that his exploration was tied to Datnowsky's plans.

In July, two of his brothers-in-law wrote to Israel, voicing their concerns about his plans to leave his current position and strike on his own.

First, on July 21, 1915, Moritz Abraham, sent Israel a short letter. Two visitors from Palestine had visited him and relayed positive news about Israel, and Moritz complimented Israel about his "dedication to work and desire to learn", but he urged Israel to put on hold his plans to leave his current position to strike on his own.

Constantinople, 21 July 1915

Dear Srolke,

Mr. Lehmann*, your colleague, who arrived here yesterday with engineer Loevy**, brought not only many greetings from you, but also the good news that you are doing very well, especially in terms of your health, and that you are full of energy in your work.

I wish that your dedication to work and your thirst for learning will continue for a long time, so that in the not too distant hour, you may reap the fruits of your many years of sowing in abundance.

I do not quite agree with you that you should intend to change your position. It may be that you have well-considered reasons for doing so; However, the point in time [1915] is extremely unsuitable for taking such a step, and the abnormal current circumstances [the war] will cause you disappointment.

I therefore advise you to hold out for the time being, for which I appeal to your unwavering patience, with a cool head and full confidence in a better fate soon.

I would be happy to hear further messages from you, and since I always take a brotherly interest in your fate, I ask you to write to me from time to time.

I remain in the usual affection,

Your: Moritz

* Albert Lehman, a former friend of Israel's from Ahlem. He came to Degania in the spring of 1914, and wrote to Israel about his plans to come to Wilhelma and work for the agronomist Keller. He might have been one of the potential partners in Israel's planned moshava.

** Joseph Loewy, mentioned previously in relation to Ronya's February letter.

It is possible that Lehman and Loewy paid a visit to Moritz Abraham to discuss Israel's plans to purchase land, as Loewy dealt in land purchases for settlers.

Although the lack of support must have been crushing, Moritz's advice was sensible, considering the current circumstances, and would prove prescient. The war had been going for almost a year, and it was now clear that the conflict would not end quickly. In addition to being affected by the war, Palestine was devastated by a locust invasion of biblical proportions which destroyed most of its vegetation. Soon, the situation would get worse: in August, the British Navy would start enforcing the naval blockade of Palestine, which would result in severe shortages and civilian famine. As for the Ottoman authorities, they would destroy the Jewish colonies, take off with the crops, and enroll Jewish settlers as forced laborers in their army, later deporting a large number of the Jewish population. These multiple onslaughts resulted in starvation, disease and the destruction of most agricultural colonies - certainly the worst time for a 24-year old to launch a new agricultural farm.

Less than a week later, it was now Israel Auerbach's turn to write to Israel about his plans, this one in a more forceful tone. Auerbach was adamant that Datnowsky should under no circumstances leave Wilhelma, at least while the war was raging. In addition, he advised him on how to avoid being drafted into the Ottoman army. Finally, he instructed him on how to safely communicate to get around the censorship from the Ottoman authorities.

Pera

11 rue Minaret*

7/24/15Dear Israel!

We were getting very worried about you when the fresh greetings from you arrived. Liska in particular was very restless, and you know that this is not conducive to her condition - after all she is expecting a successor. [Gädi, elder brother of Alex, born in 1915.]

Allow me to offer some advice, which of course I'm not forcing on you, but which is well meant and springs from an experience that is 14 years older - and what 14 years! - as yours.

Above all: for heaven's sake don't leave your post and your colony! At least not before the end of the war. And whatever your reasons might be that might make you do it, let them be silent until then.

Up close, one often doesn't see everything the way others do from afar. You may therefore pin some rosy hopes on such a change; I assure you, however, that you are jeopardizing not only your present existence, but your entire future as well.

None of your family would approve of your step, some would resent you very much; let me tell you that as a good old friend.

Endurance is the motto, as for Germany in war as it is for you, and success will be yours, as victory is for Germany.

As far as your constitutional and military circumstances are concerned, I draw your attention to the fact that, according to the law, you can only be called up for military service one year after you have obtained full Ottoman citizenship**, i.e. after your Nefus*** has been handed over.

It is now in your interest that this point in time comes as late as possible. If you have turned 24, you have the right to buy yourself free by paying the Bedel**** tax, which we want to arrange for you. [At the time, Israel was approximately 22.]

Younger people cannot free themselves with money. So it's because you get your Nefus and then your draft as late as possible. You are therefore doing the wisest thing if you are not in any way pushing to get your Nefus sooner. You've done your duty by applying for Ottoman citizenship, and can now wait for the authorities to remember you and come for you. This is also very much in your interest for other important reasons.

However, if you should receive the Nefus in the foreseeable future, do not allow yourself to be overwhelmed by any mistake made by the authorities as theirs may be, but assert your right to a full year of leave in a clever and resolute manner.

If you encounter difficulties or even feel threatened by them, go to the German Consul in Jaffa and ask him to help you. Above all, telegraph to me, m.f. the word “Protect". I have already spoken to the German Embassy here about this, and they were kind enough to promise me that the consul in Jaffa should be written to this effect and in your favor*****. So you have a right to hope for good protection and success.

But also in the interest of this cause it is important that you stay in Wilhelma! That's all I have to say to you.

You probably already know that the place where you were born, Libau, was occupied by the Germans? Windau has also been added! Hopefully Libau will remain German for all the future, so that your whole family can get rid of the Russian curse in one fell swoop.

Inshallah!

FarewellDo not write anything by post****** about the matters touched upon here, but ask the Consul to forward such a letter to me by his courier and through the agency of the Imperial Embassy. Or you can send your letter to Dr. Ruppin******* with the request to send it by post to H. Lichtheim for me.

Warm regards

Your brother-in-law

IsraelImmediately write a postcard confirming that you are staying in Wilhelma.

* 11 rue Minaret was the address of the B'nai B'rith lodge, of which Auerbach was Grand Secretary.

** In October 1914 the Ottomans demanded that all foreigners in Palestine either leave the country or accept Ottoman citizenship. This stipulation referred primarily to Jews, and particularly to Russian Jews, which is why Israel applied for Turkish citizenship.

*** "Nefus", Ladino for the Turkish "Nüfus" = identity card.

**** The Bedel tax was a tax one could pay as a substitute for military service in the Ottoman Empire. The Bedel system was apparently still in use during WWI even if unofficially; see: books.google.co.il (bottom of page)

***** During WWI, the Kaiser and his government were generally pro-Zionist (for a variety of reasons, ranging from a desire to see the Jews leaving Germany, through the strengthening of German presence in Palestine, to currying favor with influential American Jews, and the German representatives in Palestine served as protectors of the Jewish settlers. This is probably why Israel Auerbach told Datnowsky to approach the German consulate in Jaffa in case he gets into trouble with the Ottoman authorities.

****** The German postal service had several offices in Palestine at the time, and it was probably exempted from Ottoman censorship; it may be that for this reason non-Germans weren't allowed to use the German postal service during the war, which explains why Auerbach could write freely to Datnowsky but warned the latter not to mention any touchy issues in his letters (unless these were sent through German channels).

******* Arthur Ruppin was the Director of the Palestine Office of the Zionist Organization in Jaffa.

1916

Back in Wilhelma with a new position, Israel now lived in Hotel Frank, the Templer colony's hotel. (As noted by Arthur Ruppin, "the hotels managed by Germans [...] were the only ones to meet simple European standards.")

Hotel Frank, where Israel Datnowsky lived in Wilhelma.

Collection of the author

Wilhelma. To the right is Hotel Frank.

Collection of the author

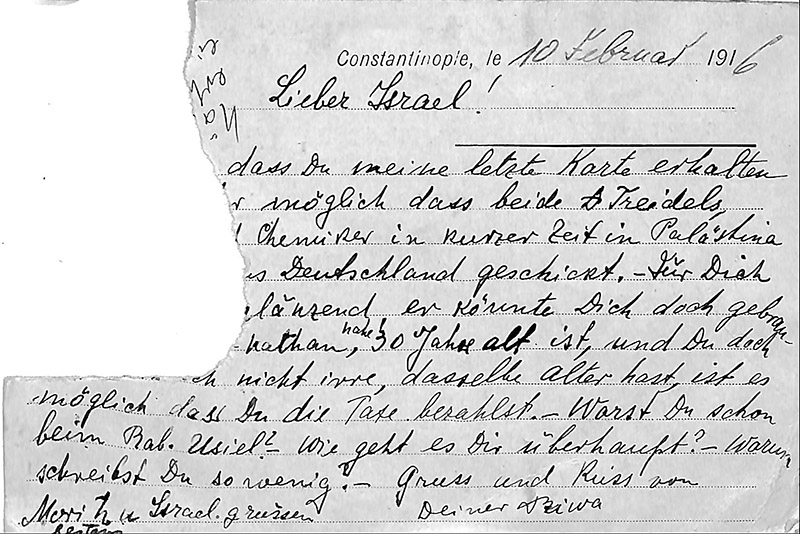

In February, Israel's sister Ronya wrote him a letter. Unfortunately, part of it was torn off, rendering most of the letter unclear. From the remaining fragments, it appears that Israel was still concerned about being drafted in the Ottoman Army. Ronya wrote "[...] don't be mistaken, if you're the same age, it's possible that you'll pay the [Bedel] tax." She also asked "Have you already been to Rabbi Usiel?".

A Jerusalem-born Rabbi who would later become Chief Sephardi Rabbi of Israel, Rabbi Usiel (Rabbi Ben-Zion Meir Hai Uziel) was Chief Rabbi of Jaffa and Tel Aviv. During World War I, he worked tirelessly for the protection of persecuted Jews in Palestine, his intercession with the Ottoman government eventually resulting in his exile to Damascus.

Since there is no evidence that Israel was religious (his journal showed that he occasionally worked on Shabbat), Ronya's suggestion that he reach out to Rabbi Usiel was most likely not related to religious matters, but to ask for his help dealing with the Ottoman authorities.

She ended her letter with the usual remonstration: "Why do you write so little?".

"The Land of Milk and Honey"

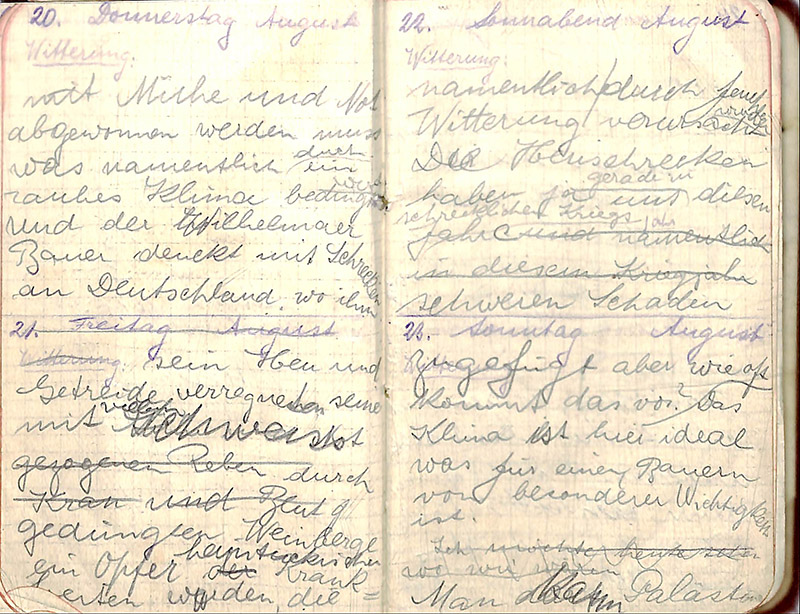

An unusual entry in Israel's notebook is the draft of a letter spanning six pages. Although written on pages dated August 20 to September 4, 1914, it was most likely written sometimes between the fall of 1915 and summer of 1916.

The handwriting is often hard to decipher, and the beginning of the letter is missing, but a few fragments seem clear enough. These are the only examples of personal observations found in his journal, and the only occurence of Israel mentioning his health and state of mind.

The letter hints at the hardships Israel had experienced over the previous year, yet he didn't sound desperate or willing to give up, and even appeared somewhat optimistic. Although vague, the mention that his "nerves suffered badly" suggests that he may have experienced a bout of depression in the recent past.

"The locusts inflicted serious damage on us* [...] especially in this war year, but how often does that happen? The climate here is ideal, which is of particular importance for a farmer.

Palestine may be described as a country where milk and honey flow, although the traveler is taught a lesson by the desolate stretches of land. Every success requires heavy worries and work that cannot be [denied?], because there is no such thing as a "Land of milk and honey".

Finally, the heat that has lasted for about 3/4 years without interruption should not be imagined as particularly pleasant.

And if one does not live reasonably hygienically, various diseases are the inevitable consequences.

I didn't have a fever or any other physical ailments, but my nerves suffered badly, mainly due to the irregular life.

Hopefully, when conditions get more normal [when [the end of] the war comes?], better times will come for me too.

I have to stop because I want to lie down a bit. It's noon, but at night it's my turn to drive the milk to Jerusalem (about 70 kms)** (because the train doesn't [?]***). And if you know the local routes and can still drive them in the pitch dark night, you will probably understand that you have to have a clear head."

Israel

* The locust infestation (March to October 1915) devastated Palestine.

** The Templer colony was situated about 60 kms from Jerusalem. It was known to be one of the rare producer of dairy goods in Palestine. According to Arthur Ruppin: "Cows' milk and butter and cheese made from it were almost or altogether unobtainable. The Jewish settlements did not produce them, and [...] the Arabs [...] kept very few cows. The chief sources of cows' milk were the settlements of the German Templers, Sarona and Wilhelma."

*** Ruppin described the train line: "[the] Jaffa-Jerusalem [railway line ran] twice daily in both directions; traveling time, three- and-a-half hours." "Traveling by train was not very pleasant, but it was incomparably better than traveling on the roads [...] Travel by coach was torture because of the number of holes in the road surfaces, the terrible dust in the summer and the knee-deep mud in the winter. [...] As a rule, in summer passengers walked the stretches that led across sand and helped the horses to pull the coach." Possibly clarifying why Israel didn't take the train, Ruppin wrote: "During the Great War, when the Turks removed the rails between Jaffa and Jerusalem and all traffic between the two towns was restricted to the roads, the journey lasted ten to fourteen hours and sometimes more." It is not clear however if this was already the case when Israel wrote this text. Other authors mention that the train continued to run but was now reserved for the Ottoman army and not for civilian use.

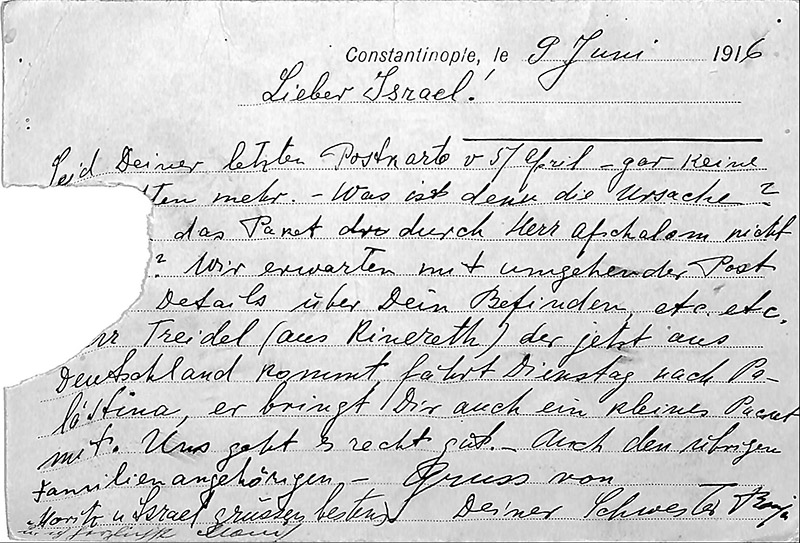

In June, Ronya sent what may have been her last letter to Israel.

She wrote: "[We haven't heard from you] since your last postcard from April 5th [...]. What is the reason? [...] We await details by return post about your condition, etc. etc." She added: "[Mr.] Treidel* (from Kinneret) who is now coming from Germany is going to Palestine on Tuesday, he will bring you a small package."

*Alfred Treidel: One of three brothers who were among the first German Zionists to come to Palestine. They built one of the a hotel on the edge of the Kinneret.

It is impossible to know what Ronya meant when she asked Israel about his "condition". Although it could have been nothing more than just a general question, it may also have been related to the nervous ailment he had alluded to.

Typhus

By then - or maybe soon after? - Israel fell ill with typhus. This seems to have been not uncommon at the time. Indeed, a few years earlier, Arthur Ruppin had noted in his memoir about Jaffa: "There was no running water, and as water was obtained from draw wells or pumped up by hand from frequently heavily contaminated wells, every summer there were typhoid epidemics." A month later, Israel would be hospitalized, as evidenced by a letter Alfred Treidel sent him and addressed to the Jaffa hospital.

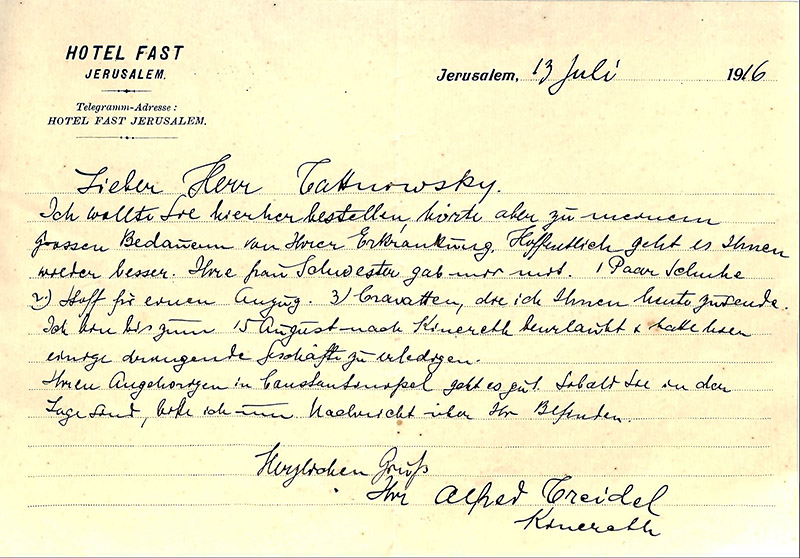

Letter from Alfred Treidel addressed to "Herr Datnowsky from Wilhelma, Jaffa hospital". July 13, 1916.

Source: Central Zionist Archives, AK384/1-3t

Alfred Treidel wrote:

"Dear Mr. Datnowsky.

I wanted to summon you here [in Jerusalem], but to my great regret I heard about your illness. I hope you're feeling better.

Your sister gave me to bring you: a pair of shoes, [...], ties, which I am sending you today.

[...]

Your relatives in Constantinople are doing well.

I'll have word of your health as soon as you're able.

Best regards,

Alfred Treidel

Kinneret

According to his obituary, Israel was treated in a Jaffa hospital, which could have been either the Jewish hospital Sha'ar Zion, or possibly the Templers' German Hospital. His health restored, he was discharged and able to return to Wilhelma to convalesce.

The mysterious death of Israel Datnowsky

Israel Datnowsky died in August 1916. He had just turned 24 years old.

According to the "official" explanation told in the family (i.e. as told by my father, who most likely learned it from his mother Ronya), Israel died of a typhus epidemic in 1916.

However, there were lingering doubts among the family about the actual cause of his death. According to Michael Rosenberg, his mother Lea, Bertha's daughter, believed that the epidemic explanation was an invention. She thought that Israel might have been involved with a married woman in Wilhelma, and would have been killed by a jealous husband.

Both of these explanations (or theories) were finally proved wrong when I found a contemporary account in the diary of agronomist and founder of the Nili spy ring Aaron Aaronsohn:

August 15, 1916, Constantinople:

"Ronya received a telegram from the Jaffa Consulate announcing the death of Datnowsky Israel at Wilhelma, following an accident. This telegram which left Jaffa on the 1st, only arrived here on the 13th."

Note: the August 1 date contradicts the date on Israel's tombstone.

According to Michael Rosenberg, since Lea didn't know about the Aaronsohn diary, she might have had some other reasons to believe in a sudden, accidental death. Michael also theorized that Ronya knew more than she shared with the family, but may have felt that the way Israel had died was a disgrace or embarrassment, and chose a more "acceptable" story.

At the end of WW1, in a letter dated November 18, 1918, Moritz, Ronya's husband, wrote to Liska's husband Asher Mallah and announced:

"[...] Sadly, Isrolke is not among the living anymore. He fell to typhus two years ago in Jaffa. I let you decide how to break the news to Liska."

This letter is surprising for three reasons. First, it means that Liska, Israel's twin sister, hadn't been told of her brother's death for more than two years. Disruption of the postal service during the war between Constantinople (an Axis ally) and Thessaloniki (an Entente ally since July 1917) only offers a partial explanation, as it didn't happen for almost a year after Israel's death. It is difficult to understand why Ronya would not have alerted her sister for almost a year.

The second surprising element is that, two years later, the communication of Israel's death went from husband to husband, and not directly between the two sisters: Ronya's husband Moritz announced the death to Asher Mallah, asking him to share the news with his wife Liska. Why didn't Ronya write to her sister Liska to let her know about the death of their brother herself?

The third surprise, this one more understandable, is the fact that typhus was blamed for the death of Israel. Since Aron Aaronsohn had mentioned the cause being an "accident" two years earlier, it seems clear that this was a cover-up.

The answer to that last question, and the final word on the cause of Israel's death, can be found in a letter from Avshalom Feinberg* to Sarah Aaronsohn** dated December 16, 1916:

הידעת, שׂרתי, שדטנובסקי שלח יד בנפשו בווילהלמה ומת לפני חדשים אחדים? אני שמעתי את זה רק בהיותי בחיפה.

"Did you known, my Sarah, that Datnowsky committed suicide ("extended a hand to [against] his own soul") in Wilhelma and died a few months ago? I only heard that when I was in Haifa."

Source: benyehuda.org

* Avshalom Feinberg worked with Aaron Aaronsohn at the agronomy research station in Atlit, where he would have become acquainted with Israel Datnowsky. A member of the NILI spy ring headed by Aaron and Sarah Aaronsohn, he was romantically involved with Sarah.

** Sarah Aaronsohn, the sister of Aaron Aaronsohn who ran the experimental station in Atlit. She was married to Haim Abraham, the elder brother of Israel's brother-in-law.

Avshalom Feinberg's description of Israel's death is more direct because, being more removed from Datnowsky, neither he nor Sarah were emotionally affected by the cause of his death. His matter-of-fact description provides a new understanding to Aaronsohn's more carefully worded explanation ("an accident"), and the wording of the telegram sent to Ronya can be understood as a way to soften the shock.

In addition to offering the most likely explanation for Israel's death, Avshalom Feinberg's letter is also interesting as it shows that both he and Sarah Aaronsohn knew Israel Datnowsky. Although it's impossible to know how well acquainted they were, it does confirm that there were a small number of people whose lives intersected: Sarah and Aaron Aaronsohn, Avshalom Feinberg, Israel and Ronya Datnowsky, Haim and Moritz Abraham.

Obituary

An unnamed friend of Israel wrote his obituary which was published in Ha-Herut, a Hebrew daily newspaper. This obituary is invaluable as it provides (or confirms) many details about his days in Palestine, and, more crucially, about his last days.

Israel Datnowsky R.I.P.

"Yet another fresh grave has been dug, and yet another name has entered into the list of lost dreamy youths with great hopes and exalted thoughts. Few would recognize the name since only a few knew him, and even fewer were his close friends who weaved their dreams with his. A cruel death has come, the same hand so common nowadays, and removed this young soul from among the few, as his goal was eluding him.

A son of wealthy parents full of agricultural knowledge, having graduated from two specialized institutions in Germany, Datnowsky came to Eretz Israel and started frequenting the agricultural school at Wilhelma in order to acquire professional knowledge suited to the local conditions.

He was there for about a year, and then moved to the experimentation station at Atlit, where he hoped to toil and acquire much additional knowledge. The scope of work in that place was too limited for him, and this youth - aspiring to advance further - found it necessary to return to Wilhelma, and here he got the position of farm manager with the agronomist Keller, replacing his friend Gibor Strauss, of blessed memory.

He started negotiating with friends here and abroad about the establishment of a new Hebrew Moshava that would be styled after Wilhelma, based on the following principles: diligence, energy, agricultural knowledge and financial property. Knowing himself and his few friends, of whose help and labours he was certain, he was sure that this dream would come true, and would become a model for many.

Until recently, even during harsh trials, he did not back away from this plan, and kept on negotiating with his "partners", until typhus came, which made him bedridden in a Jaffa hospital.

Fortunately, the doctors managed to restore his health, and, following their advice, he returned to Wilhelma to rest and recuperate until he would be fully recovered.

And as he was alone and desolate, without any close friends in Wilhelma, the passing time bothered him, and he kept on being weak.

On the 27th of Tamuz a few acquaintances spent time with him until the late hours of the night. In the morning, at dawn, his neighbors found him lying down in his own blood, moaning with intense pain. And despite the doctor's help, his soul departed after much agony.

His friends, summoned from Jaffa, prepared his final resting place in the shade of the tall eucalyptuses of the Petah Tikva cemetery, with much sorrow and grief.

May the ground where he is resting console him, this dear pioneer, and his soul and dreams be included in those who shall resurrect."

A friend

Jaffa, Av 5676 (August 1916)

The obituary, despite using metaphors, seems to confirm that Israel commited suicide: "A cruel death has come, the same hand so common nowadays [...] his neighbors found him lying down in his own blood, moaning with intense pain.".

The phrase "The same hand so common nowadays" appears to refer to the wave of suicides that afflicted a large number of pioneers from the Second Aliyah. According to Professor Gur Alroey, quoted in a Haaretz article, at least 60 young pioneers in the Jewish community of Palestine at that time killed themselves, caused by their "shattered dream":

"[...] the recognition that the society that arose in the Land of Israel did not meet the pioneers' criteria and expectations," and that "the prospects of realizing their dream were poor," brought about the "shattering of their hopes." Their disappointment, accordingly, was sometimes "too much to bear."

"Their romantic dreams were smashed in a twinkling in the face of the harsh and depressing reality of the Land of Israel. The scale of their expectations was matched by the scale of their disappointments." Having arrived with lofty ideals, [they] encountered feelings of alienation, loneliness, and psychological and social pressure. The remoteness from the family framework, the onerous work, the longings for home, the social order and the unfamiliar norms - all these only heightened the anxieties."

Israel's obituary suggests the following explanation for Israel's act: "[a] dreamy youth with great hopes and exalted thoughts [...] he was alone and desolate, without any close friends in Wilhelma, the passing time bothered him, and he kept on being weak."

This seems to echo the story of Alexander Brekner described in the Haaretz article, a pioneer from Russia who lived in Kinneret who commited suicide in 1911:

"He fired a bullet into his heart and died in terrible agonies," Naomi Shapira, a paramedic in Kinneret, noted in her own diary. "He was ill with epilepsy. And he was fed up with his life altogether. In the past few days he had an incident in which he fell and was very sorry about it. He lay in his room for three days without eating or drinking, and afterward suddenly got up in the morning and walked a little outside, went into his room and looked to see whether anyone was passing by, placed the pistol over his heart and fired and fell to the ground with a horrible shout"

Brekner had kept a diary "[filled with] disease, pain and distress, physical and mental", again an echo to Israel's letter draft where he had written "my nerves suffered badly, mainly due to the irregular life. Hopefully [...] better times will come for me too."

While Brekner's act seems to have been caused in part by unrequited loves, Israel didn't seem to have a companion, which probably contributed to his feeling of isolation.

Perhaps echoing how Israel might have felt from some of the criticism or condescending advice he received from his in-laws and his sisters, Brekner wrote in his journal:

"With my notebook I can be frank. It is the only one that will [...] not be critical either of my happiness or my sadness, the only one that will understand me, and if I should fall, in my eyes, will not debase me and will not mock me".

Although pure conjectures at this point, it seems reasonable to picture Israel in a similar situation. Separated from his family since the age of 14, he was a bachelor with few friends in the German colony. Almost 10 years after starting his agricultural training in Ahlem, then studying and working for at least 4 years in Palestine, he was still trying to strike on his own, but, most likely depending on financial support from his family, he must have been frustrated by their refusal. The impact of war and the locust invasion made the future grim. Added to all this was now the possibility of being enrolled in the Ottoman army in the near future.

All of these could easily explain his bout of illness ("my nerves suffered badly, mainly due to the irregular life.") The final straw however may have been the bout of typhus. Indeed, there are mentions in medical journals of side-effects of typhus that may include "mental confusion" and "delirium". More specifically, "Convalescence may be characterized by weakness and depression." For Israel, typhus may very well have been the last straw in the depression that would have been affecting him earlier.

Israel Datnowsky's tombstone in Petah Tikwah

The bachelor/unmarried

Israel, son of Abraham DATNOWSKY

5 of Av 5676

May his soul be bound up in the bond of everlasting life.

The date on Israel's tombstone places the date of his death on the 5th of Av 5676, which was August 4, 1916, yet, according to Aron Aaronsohn, the telegram announcing Israel's death had been sent on August 1.

After Israel's death, his friends collected his personal documents and brought them to the Palestine Office in Jaffa, presumably intending for them to be forwarded to his family. It is not clear why Arthur Ruppin - or a member of the Palestine Office - didn't do so. (I assume that A. Ruppin was acquainted with Israel's brother-in-law Israel Auerbach in Constantinople). A few years later, the entire archives of the Palestine Office were handed over to the Central Zionist Archives. This turned out to be a blessing as it ensured that the files were preserved for over a century. Had they been sent to his sisters, I suspect they would probably have disappeared by now. What happened to the rest of Israel's posessions however remains a mystery. In addition to personal effects (watch, cufflinks, etc.), there should have been more personal items, including a photo album. Also missing are official documents he would have had in his posession: Ottoman citizenship paper, Russian passport, travel visas, etc.

Israel's Social Circle

Between March 1914 and January 1915, Israel wrote the names of about 20 people, some of them multiple times. Although he only wrote people's last names without any more detail, the list is useful as some of the names can be traced to people who lived in Atlit or in surrounding settlements, often the only clue as to where Israel was at a given time.

The names include:

- Ahronsohn

- Barin

- Frères Behar

- Frau Behrman: Assuming the wife of Moshe Behrman, former manager of the Kinneret farm and a friend of Aharonson

- David Davidesco: Davidesco was one of the first settlers and founders of the Atlit settlement. His family came from Bacău, Romania, as did the Aaronsohn family.

- Epstein

- Jacob Ficherstein (?)

- Grupper: Presumably David Grupper, who had immigrated with his two brothers Eliyahu and Shmuel from Romania in 1882 and settled in Zichron Yaakov, then settled in Atlit in 1903.

- Ahron Hirsch

- Kasakevich

- Kazarkob (?)

- Lagrossa

- Albert Lehman: A former friend of Israel's from Ahlem, he came to work in Degania in the spring on 1914. He wrote to Israel about his plans to come to Wilhelma and work for the agronomist Keller. He later visited Moritz Abraham in Constantinople and may have been a potential partner of Israel's for his planned moshava.

- Lilienthal

- Loubanow: Possibly related to people from Kfar Tavor or Kibbutz Kinneret

- Meisels: Maybe Hana Meisel, noted agronomist and feminist Zionist who foundet Havat HaAlamot ("the maidens' farm"), a women's agricultural school at Kinneret Farm in 1911. Note that Israel wrote "Meisels"

- Jacob Meites (Haifa)

- Melech

- Piatner

- Risik: Maybe the Chizik family, originally from Ukraine, who lived in the Kinneret colony.

- Schwarz

- Jacob Weber

A few more names are culled from his corresponsdance:

- Sarah Aaronsohn

- Aaron Aaronsohn: Aaronsohn most likekly was in contact with Datnowsky in the experimental station. He wrote to Auerbach about recommendations he could make on his behalf, and later mentioned his brutal death in his journal. It is also possible that Datnowsky had traveled with Ronya in 1910 and had met Aaronsohn then.

- Behrman: Most likely Moshe Behrman, former director of the Kinneret Farm, later worked with Aharonson in Atlit. As mentioned in a letter from Israel Auerbach.

- Avshalom Feinberg: Indirect reference. Avshalom wrote to Sarah to mention Datnowsky death

- Frank: Could refer to Henri Frank, one of the directors of ICA (The Jewish Colonization Association) and an official of Baron de Rothschild's administration, or to Itzhak Frank, a landowner mentioned by Aaron Aaronsohn in his letter to Haim Abraham in July 1914 concerning a potential sale of his property to Haim.

- Häfer and Raz: Two names mentioned in Efraim Klein's letter who may have been common acquaitances, friends or colleagues

- Efraim Klein: Author of a letter to Israel in which he reports about work he has overseen in the fields.

- Joseph Loewy: An engineer and land trader mentioned in Ronya's letter to Israel

- Arthur Ruppin: Mentioned in Auerbach's letter. It is not clear how well they knew each other, but one can assume that they were acquainted

- Alfred Treidel: One of three brothers who were among the first German Zionists to come to Palestine. They built one of the a hotel on the edge of the Kinneret. Alfred Treidel brought a package from Constantinople to Israel, and wrote to him when he was in the hospital

- Keller: The German agronomist after whom the Wilhelma Agricultural school was called

- Flora Sänger: A young woman, presumably a Zionist friend, who wrote two cards to Israel, including a postcard with a Herzl KKL stamp.

- Gibor Strauss: Apparently a friend of Israel who previously had the position of farm manager in Wilhelma, who appears to have died prematurely

Names from calling cards include:

- Dr. Naum Isaakovich Shimkin: Dr. N. I. Shimkin from Odessa had contributed to Kadima, the organ of Southern Russia Zionists in 1906. He was an ophthalmologist active during WW1. He was later targeted by the Stalinist purges and emigrated to Palestine in the 1930's. He wrote a Russian-language play titled "Tsar Saul" in 1937.

- Menahem Sheinkin: Early Zionist leader who was a delegate to the Second Zionist Congress in 1898. He led the Ḥovevei Zion's information and immigration office in Jaffa (Agency for the Odessa Committee of the Hovevei Zion) since 1906 and was one of the founders of Tel Aviv in 1909.

- Special Thanks:

- Giora Katz, Atalya Fadida and Kineret Marciano from the Central Zionist Archives in Jerusalem, for giving me access to the personal documents of Israel Datnowsky held in the CZA and for their generous help.

- I am indebted to the CZA for preserving the documents related to Israel Datnowsky for one hundred years. Without their care, I wouldn't have been able to learn so much about his life.

- Dr. Marlis Buchholz, a historian an author from Germany, who kindly provided many previously unknown details about the timeline of Israel's stay in Ahlem and Steinhorst, and uncovered his date of birth.

- Dr. Gilad Rosenberg, for all his help translating Israel's obituary from Hebrew, reviewing my German translations, providing clarifications and insights regarding conditions in Palestine in the 1910's, and helping solve the mystery of Israel's death.

- Interviews:

- Michael Rosenberg

- Bitia Biesel

- Sources:

- xxx: Ahlem: Die Geschichte einer jüdischen Gartenbauschule (Authors: Marlis Buchholz, Shmuel Burmil, Ruth Enis, Claus Füllberg-Stolberg, Joachim Wolschke-Bulmahn, Hans Dieter Schmid, with the collaboration of Liron Amdur and Oliver Vieth. Edition Temmen, 2017)

- References and Related Links:

- Aaron Aaronsohn Diaries, Beit Aaronsohn NILI Museum

- Avshalom Feinberg's letter to Sarah Aaronsohn, from , Papers and Letters of the late Absalom Feinberg Shikmona, Jerusalem, 1975 Online version: benyehuda.org

- de.wikipedia.org (Ahlem school, German)

- chicagojewishhistory.org (Rosenwald's visit to Atlit)

- he.wikipedia.org (Atlit, Hebrew)

- www.atlit.org.il (Atlit, Hebrew)

- en.wikipedia.org (Second Aliyah)

- The Life of the Jews in Palestine (film), and en.wikipedia.org. 1913 documentary film by Noah Sokolovsky depicting Jewish Palestine during Israel Datnowsky's time. Includes segments on Zichron Yaakov and the Kinneret farm. Also included are Petah Tiqva, Rishon leZion, Gedera (50:00), Ekron, Rehovot, Tel Aviv.

- wikipedia.org (Wilhelma)

- Arthur Ruppin: Memoirs, Diaries, Letters. Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1971. Subset for 1896-1919 (pdf)

- Alexandre Mallat: "Manuscrit de la Mer Egée"