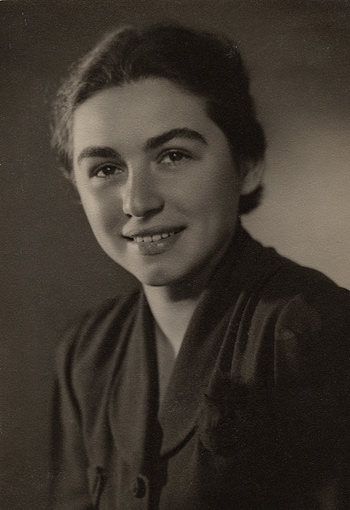

Toni Katz

My mother - Born in a Polish shtetl, she came to Germany around the age of three. Fifteen years later, a stateless Jew, she fled Nazi Germany and boarded a ship of illegal immigrants, reaching the coast of British Mandate Palestine just two weeks before the start of WW2. There she first lived in a kibbutz close to the Jordanian and Syrian borders, then later moved to Tel Aviv where she met my father. She followed him to Paris and married him in the early fifties.

A refugee twice, a survivor of three wars and a victim of Nazi persecutions that claimed the lives of her parents, she always smiled and said "I've had so much luck in my life."

Sokal

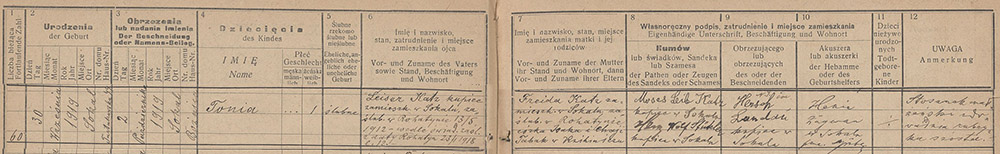

Toni Katz was born on September 30, 1919, in Sokal, a small town on the Bug river, in Galicia, the daughter of Leo Katz and Frida Tabak.

Her name at birth was Tonia, a name I didn't know until the discovery of her birth record in 2025. To all, she was known as Toni, the name she must have acquired in Germany.

I long assumed that she had been given a Yiddish name, and I vaguely remember her once mentioning that her Hebrew (or Yiddish?) name had been Toivah, which she explained meant "dove".

The name Tonia, short for Antonia, and a secular equivalent to Toivah, is not a Yiddish name, and seems to have been used in by more assimilated or urban Jewish Galician families.

September 30 1919

Sokal

House number: Tartakowska 44Father: Leiser Katz, a merchant residing in Sokal, married in Rohatyn on May 13, 1912, according to a statement dated Rohatyn on January 21, 1918, e. 12

Mother:

Had she been born a year earlier, she would have been a citizen of the Austro-Hungarian empire. Today, she would be Ukrainian. But, born just ten months after the end of WW1 and three months after the Treaty of Versailles which had made Sokal part of newly reborn Poland, Toni was born a Polish citizen.

When she was five months old, newly-born Poland declared war on Russia, hoping to take advantage of the confusion that had followed the Soviet revolution to increase its territory. Much of the fighting took place in Galicia, with each passage of both Polish and Russian armies triggering pogroms in the shtetls.

When she was one year old, the Russian cossacks fought and defeated the Polish army in Sokal. Like in other shtetls, the battle was followed by a pogrom from the drunk cossacks.

I don't know how the family experienced these days of violence, but many years later, in 1938 Germany her mother Frida would swear to never return to Poland - Nazi Germany on the eve of the holocaust somehow seemed a better place to her...

In 1920, Leo, Toni's father, left Sokal for Germany.

Like many other Jews who had suffered through WW1, the Polish-Russian hostilities and now the mounting anti-Jewish atmosphere of the newly independent Polish state, he looked towards the West for a better life for himself and for his family.

He was temporarily leaving behind his wife and children, who would finally follow him two years later.

Around 1921 or 1922, at the age of three, Toni finally left Sokal with her mother Frida and her one-year-old baby brother, Yitzhak. She would retain no memory of Poland.

Germany

1922: Toni arrived in Gera, a small town in Thuringia, Germany. She said she remembered a man waiting for them in the train station. She also thought she remembered the Red Cross helping them - although she admitted it might have been something she imagined later. If true, this would indicate that they came to Germany as refugees and not as immigrants.

Toni on her first day of school, holding the traditional "Schultuete" (school cone) filled with candies. Gera, Fall 1926.

Starting in 1926, Toni went to elementary school, then to secondary school until 1934.

According to her friend Siegmund Spiegel, Toni also went to a religious school once a week, in the afternoon, possibly the Jewish school in Meistergäßchen.

She remembered the years of hyperinflation:

"People needed a suitcase filled with banknotes to buy a loaf of bread."

She also remembered that one winter the weather had been so cold, and the country so poor, her school couldn't afford the coal to heat the classrooms, so all the children had stayed home and there had been no school for the entire winter.

Classmates, Gera, 1929

Her father Leo owned a store where he sold linen, and he did well enough to provide his family with a comfortable, middle-class life.

The Katz family kept a Jewish home: Shabbat, kosher, holidays but had little social contact with German Jews. Immigrant from the East - "OstJuden" - they were looked down upon by German Jews and attended a synagogue for Galician Jews while German Jews went to their own synagogue.

Yitzhak, Leo and Toni - Gera, 1932

Hitler years

1933: Hitler came to power.

Gera was an industrial town, mainly "working class, unionized and socialist - people were "red"".

The day the Nazis won the elections and came to power, people became terrified and submitted in fear of the Nazis.

In her school, everybody stopped talking to her. "This was not out of hatred, but out of fear." She was abandoned by all her friends.

"The only girl who continued to talk to me was actually the one girl whose father had been a member of the Nazi party since the beginning. Some of the teachers were Nazis, but not all."

Gera classmates, March 1934

1934: Toni, now aged fourteen, had to leave school because of the rising antisemitism.

"In 1934, it became impossible to continue to attend school because of the Nazi persecutions against Jews, and I had to abandon my studies." (affidavit, 1968)

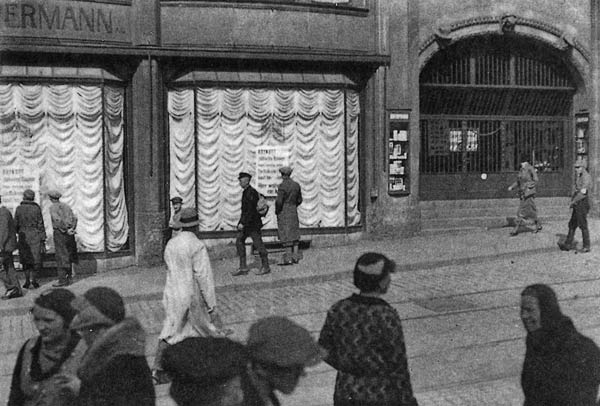

So as to not remain sitting idly at home, Toni signed a three-year contract as an apprentice in the Max Biermann department store in Gera. She started to work on May 1st, 1934. She was not yet fifteen. (Her cousin Michael Katz was also an apprentice - and later a department head - in the Biermann store.)

Biermann store, Gera.

Toni worked in the Biermann departement store for a year and a half, until the store's "Aryanization", and she was abruptly dismissed like all Jewish employees in the fall of 1935 (or December 31st?). She was a sixteen years old.

Biermann store on the day of the boycott, April 1, 1933.

(Photo from "Juden in Gera, I", Werner Simsohn)

Feeling increasingly isolated with no possibility to study, work or acquire professional training, young Jews flocked Jewish and proto-Zionist youth groups to find some communal support.

ca 1935?: Toni became a member of "Bar Kochba", a Zionist sports association, which often became a gateway to Hechalutz, which she would later join.

Note: a chapter of the "Bar Kochba" sports club was created in Gera in 1935.

Toni with members of the "Bar Kochba" sports association, ca 1935.

(Photo courtesy of Siegmund Spiegel)

1936: She was not allowed to work anymore.

Yitzhak and Toni - Gera, ca October 1936

(Photo courtesy of Shulik Mir)

Toni, Frida, Gera. October 18, 1936.

Yitzhak, Frida, Leo and Toni - Gera, October 1936

Toni, Gera - date unknown. The address of the photographer: Adolf Hitler Platz, Gera...

Toni - Gera

Toni - Gera?

Toni - Gera?

(Photo courtesy of Shulik Mir)

In 1937, Toni's younger brother Yitzhak fled Germany with the Youth Aliyah. Before his departure, the family took a series of portraits, photos that Yitzhak took with him to Palestine, the only surviving photos of Leo and Frida.

Toni, Leo and Frida, Gera, August 15, 1937.

Hachshara

1938: In the summer of 1938, Toni went to "Kibbutz Gut Jägerslust", a Hechalutz (Socialist-Zionist) Hachshara (training) center in a country estate on the outskirts of Flensburg in the north of Germany, near the Danish border. This center operated from 1934 until November 1938, when it was destroyed by the Nazis during the November Pogrom..

There, she received training for a little over four months, in preparation for immigration to Palestine.

Toni in the "Kibbutz Jägerslust" Hachshara center, Flensburg, 1938.

(Photo courtesy of Shulik Mir)

Toni, assuming in Hachshara, 1938

One goal of the training was to acquire an occupational training that would fulfill the requirements of the British mandatory power with regards to the qualification of Jewish immigrants to Palestine (workers/employable labour between the ages of eighteen and thirty-five)

The Hechalutz did not however regard itself as a organization for occupational training; its aim was to alter the "complete person" in the course of a personal Hachshara and Aliyah in accordance with the Zionist ideal.

The Hechalutz contrasted the style of life of the chalutzim (pioneers) with that of the bourgeois, highly assimilated German Jewry.

This goal did not only consist of learning Jewish history, knowledge of the Palestine region or an elementary grasp of Hebrew. The Hechalutz wanted to be sure that German Jewish emigrants to Palestine were committed to the Zionist cause. That meant self-sacrificing work in the service of building a "Jewish home".

The Hechalutz believed that a period of ideological preparation should precede the occupational training. It was also important that these young Jews should lose the illusion that an "agreeable" life awaited them in Palestine. The Hechalutz made it plain that life in Palestine would be earnest, primitive and hard.

The young people were to understand that they were to subordinate themselves to the national task of Jewry in Palestine.

The consequence of this was that the applicants' viewpoint became the decisive criterion whether or not a young Jew acquired a Hachshara place. In this sense the Hechalutz regarded itself as an "education movement" (or one might say "reeducation").

The Hechalutz's emphatically "Jewish" educational objective brought it into conflict with established German Jewry. Many saw a distinctly Jewish education as a conscious departure from Germaneness. Jewish youth saw their decision for immanent emigration to Palestine in sharp contrast to those who had decided to remain in Germany despite the ostracization and discrimination.

(above excerpts from http://www1.uni-hamburg.de/rz3a035//borchardt.html)

It seems that Toni originally planned to emigrate legally, like her brother Yitzhak had done a year earlier. However, at 19, she was already too old for youth Aliyah and needed to participate in the training program to hopefully qualify for the limited certificates available from the British Mandate authorities.

What her training consisted of is not known, but we can assume it focused on the housekeeping activities that were assigned to young woment: preparing food in the kitcheen, washing laundry, ironing, darning, etc. She may have been able to receive some agricultural training towards the end of her time there, but this is not confirmed. (Anne Dreyfuss declared that he finally was able to do some field work for a month and a half: "Potato, beet and corn crop. learning threshing, milking, loading manure, leading horses, carrying 130 pounds."

One of the girls who had joined the Hachshara around the same time as Toni was Lilli Dreyfuss. She wrote to a friend, describing the group of young woman in the Hachshara:

"We didn't have many nice girls. Except for the ones you know [from Bochum], [there was] only one [...] her name was Toni Katz [...]. She was the only pretty one. Black, slim [...] Very hardworking and quite smart and confident, but strangely only popular with some... The others are all uninteresting."

It seems that in the three or four months that her stay had lasted, Toni had managed to make enough of an impression, not just with her looks, but with her work ethics, intelligence and personality. The reputation she developed during these few short months most likely were key in her getting invited soon after to be one of the passengers on an illegal ship, which would help her flee to freedom and safety.

1938, October 27- 28: Across Germany, a one-day "Aktion" was planned for October 28 to round-up all the Polish Jews and expel them back to Poland. The leader of the training camp (or the owner of the estate?) had been alerted ahead of time by a sympathetic local of the incoming "Aktion" on the training camp, so he sent everybody* to hide in a movie theater for the duration of the Aktion, which was supposed to go utnil midnight.

*note: I always understood from what my mother had told me that the entire group had gone to hide in a cinema during the Aktion, but it was probably only the few Polish Jews from that group who were targeted by the roundup who actually hid, as German Jews were not affected by the Aktion.

Most of the Jews in the camp were German, but Toni, along with a few others, were Polish and were thus the target of the nation-wide hunt to deport all Polish Jews back to Poland. Three days later she would officially become "stateless", having lost her Polish nationality.

The same day, 300 miles away, in Gera, her parents Leo and Frida were deported to Poland, along with 17,000 Polish Jews.

1938, November 9-10: Kristallnacht.

About Kristallnacht, Toni once said "Ah... la on n'a pas rigolé..." - "Well, that wasn't fun..."

From Toni's affidavit (1955):

"After approximately 4 months there, the Gestapo arrived one morning at 4 am. We were all arrested, and taken to preventative arrest in Flensburg. The women were let go during the day, on condition that we would leave the camp immediately. The men were taken to a concentration camp (KZ). While we were arrested, our camp was entirely destroyed by the Gestapo, so were our personal belongings."

She told me that they rounded up everybody and took them to jail, but were polite and rather "easy going". They kept the girls for a few hours, then let them go. The boys however remained under custody and were later sent to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. They would later be released at the end of December, after providing proof of their plans to emigrate.

They showed them a pile of things, were told to go through the pile and pick up their belongings, and Toni did manage to retrieve what belonged to her. When they got back to the estate, everything, including the furniture, had been destroyed by the local Nazi thugs who, just a day before, were still playing cards with the owner of the estate. Alexander Wolff, the owner, was also arrested, although he managed to escape to Denmark.

Note: It is surprising that Toni was let go and that nothing worse happened to her that day. Being from Poland, she was supposed to have been deported to Poland ten days earlier, and was now a "stateless Jew". As such, she didn't have a German id card or passport. Were the Gestapo agents careless and did not ask for identification? Or lenient? Was she able to somehow convince them that she was German?

Toni journeyed back home, but travelling across Germany as a "stateless Jew" was difficult and probably fraught with dangers.

"I then left illegally for Hamburg. I was helped there by the Jewish community, which helped me get back to Gera." (affidavit)

Toni somehow managed to get back home to Gera, only to find the family apartment abandonned. Her parents had been among the 17,000 Polish Jews rounded up and expelled back to Poland during the October 28th deportation. The dinner table was set, and in the oven was a partially baked cake, signs of the haste of their departure.

Toni, outside of Gera. Dated January 1939, but probably earlier. Photo sent to Siegmund Spiegel.

(Photo courtesy of Siegmund Spiegel)

In Gera, Toni was able to hide with friends of her parents. She stayed with the family (the wife) of her former employer*, a department store owner who was incarcerated in a camp and was badly beaten. (*assuming The Biermann family).

She also stayed with the family of her friend Esther Flieg. She gave them some money from the sale of some of the furniture and other things she had managed to liquidate from her parents' apartment.

She retrieved money that her parents had left with friends, and sent it to them in Krakow via a smuggler (an SA, or something similar?), who kept part of the money, but Leo and Frida did receive some of the money, which allowed them to get a one room apartment with a kitchen in Krakow.

A little later, Toni sent them some of their furniture and belongings, so they could furnish their apartment in Krakow. According to Mary Frankel, who was in Krakow with Leo and Frida at some point, they did receive some of the furniture, while some of it never arrived - Toni's dowry being among the things that disappeared.

She had liquidated everything (or "part of the things"? she probably sold the merchandise, and part of the furniture and things she didn't send to Krakow), and sent everything to her parents, with the idea that she too would go to Krakow to be with her parents.

Toni then went to Weissenfels, a town 50 miles from Gera, and stayed with Mary Frankel. Mary had returned from Poland in the spring to liquidate the family apartment and store, and to wait for American visas for her and her son Max.

Max Frankel:

My mother went back to Germany from Krakow in the spring of 1939 while my father and I stayed in Poland. She had permission to liquidate our apartment and store, and packed crates for America, etc.

Her real motive was to finally secure U.S. visas in Berlin, but she spent much of those weeks in Weissenfels, and that is probably when your mother was with her.

Tony said she lived for three months with "just a handbag and a toothbrush", while she stayed with Mary.

Escape

By then, Toni had planned to go to Poland to join her parents. Her parents had told her that "this way, at least we will all be together". She was set to take the train to get to the Polish border at midnight the next day. She said she had "knots of fear in (my) stomach", as she would have to use a smuggler to cross the border, as going to Poland was now illegal*. (*Because she was now stateless.)

The day before her departure, she received a letter from the Hechalutz organization that let her know that, if she wanted, they would hold a spot for her on a ship for Palestine. The ship would be ready to leave in the next three days.

She called her parents in Krakow to ask them what they thought she should do: should she come to Krakow and be with them as planned, or should she instead leave on this illegal ship and try to reach the shores of Palestine despite the British blockade?

A year before, her parents had been upset at Yitzhak's decision to leave for Palestine with Youth Aliyah. Now, a year later, their situation had changed dramatically. Although the war hadn't broken out yet, they probably could sense that the situation was going to worsen and realized that being in Poland meant being trapped, without any possibility to get out.

They told her to go and said: "This way, we'll know that you at least are safe."

Sixty years later, talking about the timing of this letter, and reflecting on her decision to change her plans at the very last moment, with the blessing of her parents she never saw again, she said "J'ai eu beaucoup de chance dans ma vie...", "I've been very lucky in my life..."

The promised "three days" turned into three to four months of waiting and hiding, as delays after delays pushed back the departure date.

Finally the day came, and she traveled across Germany, from Gera to Belgium, illegally, by train.

She was only allowed to leave with one backpack with 8 kilos of belongings, including a wool blanket*.(* I assume these were actually the directives from the Aliyah group).

She went to Cologne (Köln), stayed there for a week in a Jewish house (or center) ("horrible" she said).

When we were in Köln in 1976, she pointed to a phone booth in the street, in front of the main post office. She said this was where she had spoken to her parents for the last time, from that same location. Although I believe this would have been illegal then, Jews not being allowed to use public phones.

1939: In May, 1939, she finally managed to flee Nazi Germany.

She crossed the border between Germany and Belgium, illegally of course. Being stateless, she could not get a visa, and so no country would allow her in. A stateless Jew from Germany, she was one of the many unwanted refugees that no European country wanted to welcome.

I assume she crossed the border as part of a group of chalutzim.

She went to Antwerp, and was reunited with the entire group, one hundred young German chalutzim. Once again, delays meant they had to wait for the boat. This time the waiting lasted one month.

First, they stayed at the Maccabi clubhouse, sleeping on straw on the floor, one hundred youngsters. Members of Maccabi would come to flirt with the girls.

Then she went to stay in the house of a wealthy Jewish family who were away for summer vacations. Four boys stayed upstairs, four girls downstairs. One day, the Belgian police came, alerted by the denunciation of a neighbor that illegal aliens were staying in the apartment. They took the young men to jail, where they would remain until their boat left, or could give assurance that they were planning to leave. The police hadn't noticed the girls who were on the lower floor though, so they were not arrested. The appartment being deemed unsafe, they left and went back to stay at the Maccabi clubhouse.

(Another time, I think she said that the police simply wanted to make sure that the illegal aliens wouldn't end up staying in Belgium. They were told that the German Jews were waiting for a boat to take them, so they would arrest the men for the day, then would release them, then would arrest them again, etc. until the time when the boat was finally ready to leave.)

Leaving Europe

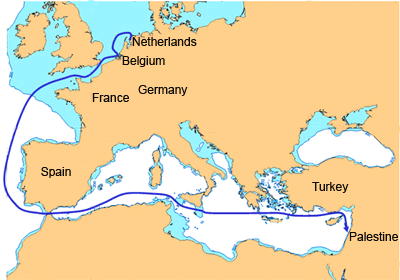

1939, July 18: after several months of delays, the ship that would bring her to Palestine finally arrived. It was a steamboat called the Dora. The boat had been commissioned by Mossad le Aliyah Bet to bring them to Palestine despite the ban of the British mandate authorities - as illegal immigrants.

When they first saw the Dora in the harbor, people in her group remarked that the vessel was way too small for so many people, and wasn't suitable for such a long trip. Toni - "naive as I was" - told them that, "of course, this is just a little boat that will take us to the real boat, which must be somewhere in the high sea. They don't want to bring the real boat in the harbor because it would give it away..." But she was wrong. That "little boat" was in fact the ship that would take about 480 Jewish refugees through a four-week trip, from the North Sea and the Channel, down the Atlantic Coast, then through the Strait of Gibraltar into the Mediterranean, where they would have to avoid the British navy on the lookout for such illegal boats.

They finally sailed away from Vlissingen on July 18th, 1939.

The Dora.

Photo: De Maasbode Van Woensdag, 19 July 1939

On board, the arrangements were quite rudimentary. They slept on wooden planks, 3 people lying head to foot, with a space about 30 cm (12") per person.

Half-way through the trip, the Greek crew went on strike and said they wouldn't go any further unless they received double the money. Toni then noticed her friends walking around with handguns in their belts, which apparently seemed to solve the rebellion.

They stopped for one week in a small remote port in Turkey, waiting for the right time to land. They radioed Palestine, waiting for a moonless night when they could land without being caught by the British navy.

There was a small Jewish community there, who asked them to let some men come down ashore so they could have a minyan. The group leaders refused to let anyone get off the boat. Anyway, the Hechalutz leaders didn't care much about shabbat or anything religious.

One day, local people brought fresh water in boats, with their feet in the water. Everybody rushed to drink the water, because all they'd had was slightly salty water for the entire trip. They also brought watermelons. Later, everyone got sick. Ever since that day, she'd never liked watermelons. (I also remember a different version: the water was bad, and she alone didn't drink it - so she was the only one who wasn't sick. She'd only had watermelon.)

The Dora odyssey

They finally arrived in Palestine on August 12, 1939, landing in Shfayim. She said she'd jumped in the water to reach the shore.

On the shore were people waiting for the refugees, who gave them clothes and IDs, so they wouldn't be arrested if the British soldiers found them. She thought maybe the patrols had been paid off not to find them.

She said that the British soldiers found the Dora in the morning, and that was the last trip the boat made. However this was apparently not the case. It seems that in October 1939, after the start of the war, the Dora was chartered to carry passengers from Constanza, but the departure was cancelled.

Eretz Israel

1939 to ?: Right after her arrival, she went to a kibbutz in Raanana. The first person she met there was Dan Birnbaum, the brother of her friend from Gera, Ruth Birnbaum (Lessing). All the boys wanted her/them (?) to stay - she said: "they wanted German girls, they were tired of the other girls..."

Toni, Tel-Aviv, 1939

1939?1940?: After a short while, she moved to Kibbutz Maoz Haim with other new immigrants. Maoz Haim was a "wall and tower" kibbutz that had been established in 1937 in the Beit She'an valley. Adjacent the Jordan river, it was a more remote location a mile or so away from the Jordanian border and about 10 miles from Syria's Mount Hermon. There, they started from scratch, living like pioneers. They slept under tents, erected watchtowers, built prefab houses, (Dan Birnbaum was in Maoz Haim too - we will meet him went we visit in the 70s.)

Toni, with Dan Birnbaum. Kibbutz Maoz Haim, 1940

Toni and Dan Birnbaum, Maoz Haim, 1940

Toni and Dan Birnbaum, Maoz Haim, 1940

Toni, Maoz Haim, 1940

Toni said that upon first arriving in the kibbutz, people had to give everything they had to the group. All personal possessions went to the kibbutz, and were then shared, including clothes which were rotated weekly.

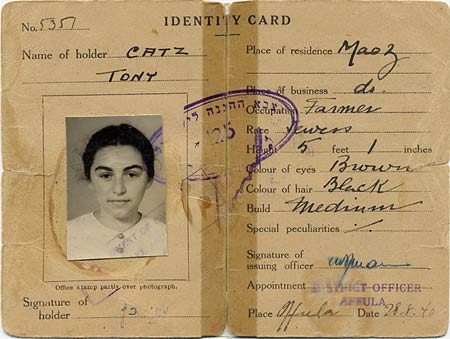

Identity Card, Palestine Mandate, 1940.

August 1940: Toni was issued an ID card delivered by the British authorities of Mandatory Palestine.

"Tony Catz" lives in Maoz, she is a "farmer", and her "race" is "Jewess" - this last detail a surprising echo of what would have appeared on her identiy papers in Germany at the time. Of course, it's impossible to know if this was a genuine document or a fake, since she would have received a fake id card upon landing in Shfayim the previous year.

When we visited in the 70s, she described her life there at the time. At first, they had lived in tents. The first building was the communal dining room. Next, I think, was the hen house, then maybe the school, or the dorm for the kids. Houses for people came last.

First Marriage

1940: July, 16th, Toni married David Ben Nachman Liebergot. Although they would be married for eight years, the marriage would not be successful. The couple had no children.

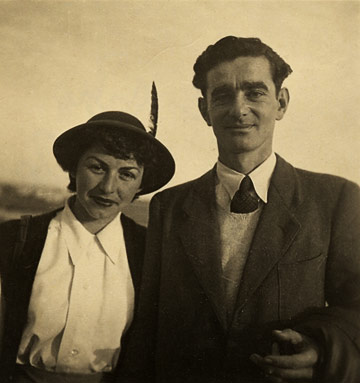

Toni and David Liebergot* (?), Tel-Aviv, 1946?

* This may actually be Ugo Gnagnati, a friend of Uriel's, and not Liebergot.

David Liebergot was, according to his cousin Alex Neuhoff, a "very nice boy" but didn't have a profession, so he helped his adoptive father with his work buying ans selling ceramic.

194?: Eventually, Toni left Maoz Haim.

It's not clear when Toni and her husband left Maoz Haim for Tel Aviv, but this would be as early as May 1941, as evidenced by the address she used on the Red Cross card she sent her parents:

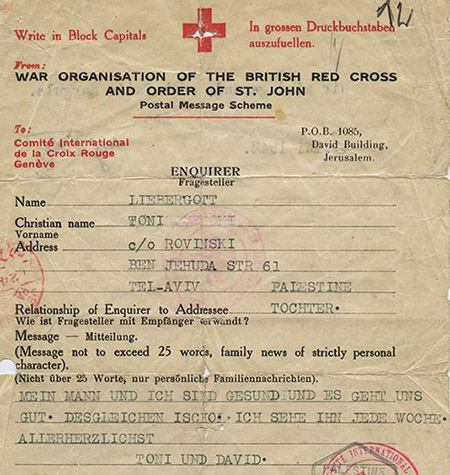

Rec Cross card from Toni to Leo and Frida, May 1941.

There, they lived in a room in David's adoptive parents' apartment, David and Sonya Ruvinski.

"After Maoz Haim, I lived until 1950 in Tel-Aviv, where I worked as a household employee ('employee de maison') and worked in a flower shop as a saleswoman."

Toni, Tel-Aviv, 1943

Toni and Yitzhak, Tel-Aviv, 31 March 1943

Toni eventually found work managing a flower store on Ben Yehuda avenue, close to where she lived.

Flower shop

1945: letter to Riva:

"I am working as usual at the little flower shop, a very good job, I still have plenty of time just for myself."

Enter Uriel

Alex Neuhoff, a cousin of the Mrs. Rovinski was a close friend and roommate of Uriel Abraham. One day he introduced Uriel and Toni.

According to Alex Neuhoff, "when Uriel and Toni met, she wasn't separated yet. They would meet with friends on the beach in Tel Aviv, to play paddle ball - that's how they met".

194?: Toni later reminisced about palying paddle ball on the beach in Tel Aviv with friends.

Tel Aviv beach, 194?

One day, Uriel came home and told Alex: "I think I'm in love with the florist."

194?: Tel Aviv. Toni learned photography at Schimmel's, and modelled for a series of photographs.

Toni, Schimmel's Photography, Tel Aviv.

1947: There is a photo of Uriel with "copyright Toni" - so they knew each other already.

1948: Photos of Toni and Uli together

Toni and Uriel in Tel Aviv - 1947 or 1948

1948: August 12: She officially divorced David Liebergot.

1948/1949: Toni worked in a Kindergarten in Tel Aviv.

Toni, kindergarten, Tel-Aviv, 1949

1948: Confused... I thought she said she didn't go in the army because being in a kibbutz on the border was considered being part of the defense lines - but it seems she was in Tel Aviv then?

1948: She had mentioned seeing the sunken remains of the Altalena on the shore of Tel Aviv - so she had to be in Tel Aviv around 48/49.

1949 September: Uriel left Tel Aviv and returned to Paris, to be with his mother. Toni would follow him a little later.

1950: End of 1950, Toni left Tel Aviv and went to Paris to be with Uriel.

1951: February, 27, Uriel and Toni got married in Paris. (From "Antwort auf die Auflage der Behorde, 1966") - although their ketouba is dated 25 June 1951. Two ceremonies more than one year apart?

1951 Alliance Francaise, Paris

1951 Unesco, Paris

1952? or 1954-1956: Toni worked in Rachel Gordin's Jewish Montessori Kindergarten. She may have started even earlier, as there is a photo from Hannukah 1952.

1955 Toni and Uriel were still living in Ronya's house, 35 Rue de Lubeck, Paris 16.

- Interviews:

- Toni Abraham, nee Katz

- Siegmund Spiegel (Gera years)

- Alex Neuhoff (Palestine years)

- Special Thanks:

- Shulik Mir, for sharing family photos

- Siegmund Spiegel, for providing much of the information included on this and other Katz-related pages, and additional photos

- Max Frankel, for the 1926 photo of Toni on her first day to school

- Chaya Brasz, for graciously allowing me to post a translation of her article on the Dora

- Erik Post, for translating Chaya Brasz's article on the Dora

- Bernd Philipsen, for his book "Jägerslust", and for kindly providing additional information on the Hachshara center in Flensburg

- Oksana Savchuk-Tsarynska, for discovering Toni's birth record. (2025)

- References and Publications:

- The "Coffin Ship". Vrij Nederland. May 1, 1993..

- "Jägerslust" : Gutshof, Kibbuz, Flüchtlingslager, Militär-Areal. Gesellschaft für Flensburger Stadtgeschichte, 2008.

- Juden in Gera vol I, vol II Publisher: Hartung-Gorre Verlag Konstanz