Mary Katz & Jakob Frankel

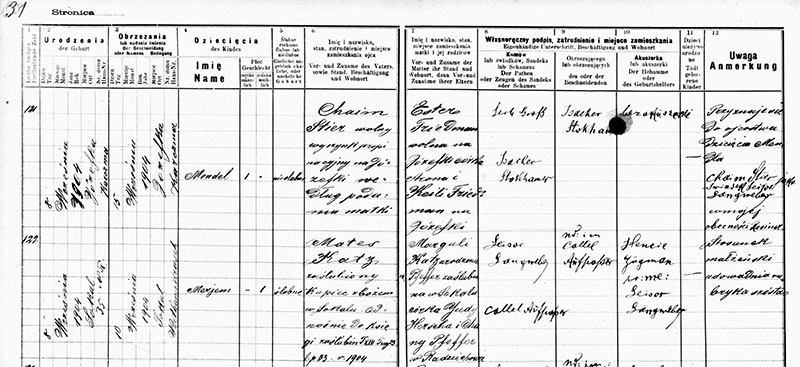

Merjem (later: Mary) Katz was born on September 8, 1904, in Sokal, house number 35, the daughter of Mates Katz, a merchant from Sokal, and Margule Pfeffer.

Her family left Sokal and came to Gera when Merjem was around 10 (?) years old. (Her father came before WW1, but the exact date is not known, and it's not clear whether he came alone at first or with his family.)

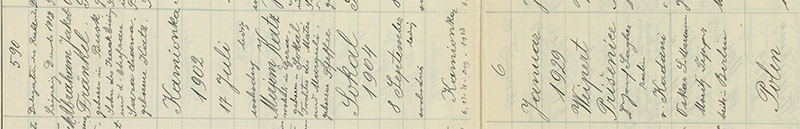

On January 6, 1929, she married Abraham Jakob Fränkel in Kadaň, Czechoslovakia, 100 miles south of Leipzig. (The Fränkel family originally came from Busk, a shtetl about 60 miles south of Sokal, and had also emigrated to Gera before WW1.)

Groom: Abraham Jakob Fränkel

Born in Busk

Son of Isaak Eisig and wife Sara Chawa, née Katz.

Kamionka (county)

July 17, 1902

Bride: Merjem KATZ

Lives in Gera, born in Sokal,

Daughter of Mates and Marguli, née Pfeffer

in Sokal, September 8, 1904.

January 6, 1929

Rabbi Joseph Sagher

Kadaň

Witnesses: Oskar Silbermann, Moritz Tepper

Polish

Although born as citizens of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Jacob and Mary both had Polish passports as Sokal and Busk belonged to Poland since the end of WW1.

Max Frankel:

"My parents' passports were Polish, not German, although neither spoke Polish and had not lived in Poland since early childhood. Actually, they never lived in "Poland" at all; when Papa and Mutti were born, in 1902 and 1904, Poland had undergone one of its periodic dismemberments. Their native villages, proverbial shtetlach named Busk and Sokal, were dots on the map in a region called Galicia of what was then the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The region became Polish again after World War I, in 1919; it became Soviet at the start of World War II, in 1939, then German, then Soviet, and finally Ukrainian at the end of the Cold War, in 1991. The Jews of Galicia could have amassed a colorful array of passports if only they had survived these permutations.

The Frankels of Busk and the Katzes of Sokal migrated separately before World War I to the city of Gera in German Thuringia and took apartments in adjoining streets. They came in search of economic opportunity, which they found by buying and selling rags and cheap clothes, but they never lost the stigma of being Ostjuden, Eastern Jews. Even without the ethnic instruction of the Nazis, the German Jews looked down upon the scruffier ones from the East and not infrequently wondered aloud why they didn't go back where they came from. The Ostjuden looked too Jewish and talked too Jewish; they were embarrassing obstacles to the German Jews' "assimilation," which was an exercise more in hiding than in merging. The bent and bearded caricatures of Ostjuden that German Jews carried in their heads looked very much like the pictures the Nazis drew to portray all Jews everywhere.

Still, Papa and Mutti lived easily with these distinctions. They thought of themselves as born in Austria-Hungary and only perversely branded Polish; they felt like Jews and lived like Germans.">

Their son Max was born in Gera on April 3, 1930. Six months after his birth, the family moved to Weissenfels, a small town 40 miles north of Gera.

Max Frankel:

We lived in Weissenfels, a well-scrubbed town in Saxony, near Leipzig, which manufactured shoes, staffed the Leuna chemical works, and served as a minor railroad hub for central Germany.

[...] The quest for their own business took them from Gera to Weissenfels shortly after I was born. The chemical workers promised to be good customers of my grandfather, a peddler, and his son, who dreamed of opening their own dry goods store. There were no major tensions between the 120 Jews and 40,000 Germans of Weissenfels. The Jews were prominent among the merchants, lawyers, and physicians; many of them had assimilated clear into mixed marriages. The fathers of our town's German Jews had fought for Kaiser Wilhelm II in World War I, and they would have fought for Germany again if allowed. We were the only Jews in town who did not possess German citizenship, and our political views were a smidgen less Germanic than those of the rest, but we were respected members of the Jewish congregation and accepted members of the larger society.

Mom often testified that until the Nazis came along anti-Semitism was something her parents talked about only in tales of the old country. In Weissenfels, she said, the most common distinction between Jew and Gentile arose in discussions of servants: people thought a German girl trained in a Jewish household was less desirable–she was 'too spoiled.'"

In 1933, Jakob and his father opened their own store. Max Frankel:

Frankel became a well-known name in Weissenfels on New Year's Day in 1933, when it appeared in large letters above the entrance of a store at one corner of the town's main marketplace. The store carried stockings and handkerchiefs, suits, dresses, and some shoes, and on special order it could provide tables, beds, and sofas, even an occasional icebox or piano. Opa Isaak Frankel, my grandfather, and his energetic son, Jakob, acquired their goods in Leipzig or Berlin, added a modest profit, and delivered wherever you wished. And if the buttons on your suit had to be moved or a dress needed shortening, Jakob's wife, Mary, was at hand a few hours each day with pins in her mouth to make the garment fit. The appeal of the Frankels lay not only in their cheerful one-stop service but in their apparently trusting nature: they let even 1,000-mark items out of the store with only a small down payment, and, after months of weekly collections, when you were close to settling the debt, they would urge you to take home some other goods with "nothing down." As in his prior peddling enterprise, Pop kept bundles of neat account cards for the installment buyers and used a secret code to brand each one as a good risk, doubtful, or bad. The business was full of promise had Germany not gone berserk.

Siegmund Spiegel:

"Jacob Frankel's father, Isaak Frankel, they had a better business, and Jacob Frankel, in Weissenfels, had a very good business. They were held to be much better off than the families in Gera."

Soon after the opening of the store, Hitler became the chancellor of the Reich.

Max Frankel:

It was only twenty days after the store's grand opening that Adolf Hitler became Germany's chancellor. The Fuhrer was a well-advertised phenomenon. He and his brown-shirted hoodlums had demonstrated their skill at government by blaming economic distress on the Jews and by bashing skulls, even in little Weissenfels, of people like Herr Franz, my nursemaid's husband, because he called himself a socialist. The Jews and socialists of Weissenfels, and also a great many other people, were uneasy about the Fuhrer's accession. But many expected the Nazis to fail and disappear in short order; they had promised much too much, it was said. Others were more impressed that this charismatic foreigner, an Austrian, so well understood Germany's humiliation in war and desperation after economic collapse. Like him or not, most Germans said, Hitler came to power lawfully, a very important fact in such a fastidious society.

In our town, folks began to waver about this choice on Saturday, April 1, 1933, the day on which the Nazis ordered a nationwide boycott of every Jewish business. Two brown-shirted storm troopers patrolled the front of our store with signs instructing people not to buy from Jews; presumably, they also carried blackjacks to enforce the request. No one came that day. But on the following Monday, my third birthday, the troopers were gone and a good number of our faithful patrons returned, some through the front door and a fair number, including Gestapo detectives, through a back door. They were elaborately apologetic about the boycott and asked forgiveness for their cowardice. You know how it is, they kept saying, and they guiltily purchased an extra sheet or dress. In a sense, we Jews were fortunate to have been spared their humiliating dilemma.

Still, maybe half our customers gradually disappeared, and the least honest among them even stopped paying their debts. Jewish haters soon lost the right to press our claims in court. Hitler's 1,000-mark bonus for newlyweds could no longer be redeemed in Jewish stores. Some of our non-Jewish competitors atoned for their greedy pursuit of our customers by paying Pop "commissions" for "referrals." The Jewish owners of large department stores in Leipzig and Berlin were thrown into panic; they advertised frantically that they no longer employed Jewish salesclerks so that customers could be assured of dealing only with pure Aryans. Some of their suddenly unemployed clerks arrived in Weissenfels, where our Jewish community tried to absorb them. But no amount of improvisation could long shield us from the rain of Nazi decrees.

Over the next two years, Jews were barred from most professions and even from most public places. The Jewish salesmen who supplied our store were forbidden to enter hotels and restaurants and could barely function. We could no longer sit in the coffeehouse or go to the movies or swim at the Saale River beach. Mom's dressmaker no longer found time for her orders, and her beautician no longer granted appointments. By the end of 1935, even the minimally Jewish German Jews, who had successfully camouflaged themselves and whom we Easterners derisively called yekkes (probably because they wore Jacken–jackets) had been stripped of their German citizenship. Such Germans became Jews again, even if they were only half Jews, quarter Jews, or one-eighth Jews. Those who had struggled hardest to acquire the coloration of their surroundings were among the most conspicuous now that their environment was transformed. They no longer fit in anywhere.

By necessity, the Jews of Weissenfels drew themselves into a tighter community. They founded Zionist clubs and prepared their youngsters for flight to Palestine. The Jewish Agency, looking to claim that holy land by outnumbering the Arabs, recruited settlers under the age of thirty-five and also "capitalists" of any age if they paid their way with 1,000 smuggled English pounds (about $5,000) each. Older folks thought of leaving, too, but the fear of change, the dread of a new language, the separation from relatives, and the loss of familiar comforts held them back. They would tolerate segregation and discrimination for a time and vied in the invention of new hopes: they might be legally exchanged to some other country (Madagascar was prominently mentioned); surely the 1936 Olympics in Berlin would require the Naris to display a new spirit of tolerance; maybe Hitler would overreach and fall from power, or the civilized world, whatever that was, would finally intervene and throw him out. Much as safety often produces dread of disaster, fear created endless hallucinations of rescue. The more miserable our condition, the more certain we became that it would not, could not, get worse. No one even imagined death camps.

In those still early Nazi years, only two Weissenfels Jews were actually arrested: young Hoffman, the playboy son of a cattle dealer, and young Tasselkraut, a salesman's son, both in their early twenties. Hoffman, people thought, went to a dance with a non-Jewish girl and probably infuriated some Nazi suitor. Tasselkraut's offense has been forgotten, though the charge against both was something about reading forbidden newspapers. Their sentence was a year in Buchenwald, the nearest concentration camp. Both were released after two months on condition that they leave the country. Hoffman went to Palestine, Tasselkraut to Britain. It's assumed that their parents paid handsome ransoms; indeed, extortion may have been the impetus for their arrests. The non-Jews who still confided in the Frankels were suspicious of the legal proceedings, but they could not bring themselves to concede that the boys were altogether innocent. Maybe they were Communists, people said, with a delusionary logic that I would encounter again in many places.

Max Frankel

From the age of memory, I was learning to cope with the world's bizarre delineations of nations and each one's rules and rituals of exit, entry, and citizenship. Maps, visas, permits, and passports were among my toys and lesson plans. I was being trained for refugeedom, primed to be dropped into a Palestinian desert or a Latin American jungle. And I learned not only to distinguish between lawful and illegal transactions across borders but also when and where and with whom one could safely discuss such things. In short, I was well rehearsed for the melodrama of our flight from Hitler, even though our family botched it in performance.

I had learned to read pretty well before entering Herr Weber's first-grade class. I also wrote well, except for the damned inkblots for which you had your knuckles rapped with a ruler. (Tearing a page out of the penmanship book was a capital offense.) But I bore a greater grievance against Weber. Twice each week, before the Hitlerjugend hour, he would gently order me, the school's only Jew, to leave for home. I hated that isolation, as I hated being the only kid in school without a brownshirt uniform and the only one living behind windows that didn't fly a flag on holidays. I flew into a screaming, stomping rage one night when I spotted Herr Weber and my classmates bearing fiery torches and bloodred swastika banners past our house behind a loud, magnificent marching band. Weber regularly consulted my parents to ask how else he could shield me from the name-calling and pummeling at school and also how he might soothe my wounded pride. He was such a kind man, Mom kept telling me as she explained that we Jews just had to put up with distinctions, like not having a Christmas tree.

Since I ate Christmas herring and boiled potatoes and stollen at the home of Frau Franz, our housekeeper, and enjoyed eight days of Chanukah celebrations at home, I felt no religious deprivation. It was the exclusions at school that hurt and that compelled me to find anchor in a mostly adult world. I had only one playmate, Dieter, the barber's son, who lived downstairs and with whom I drove soccer balls the length of our apartment's corridor. I played cards with Opa and chess with Papa and solitary games with myself; I worked easy crossword puzzles, scratching the answers with pins when forbidden to "write" on the Sabbath. I walked alone to school and to synagogue, breaking into a trot whenever I passed through the tunnel beneath the railroad tracks so that I could imagine myself winning a long-distance race; I used the tunnel's echo to produce the sound of a cheering throng. Since I was not a fast runner, the race was an obvious metaphor by which a lonely kid devised his own paths of triumph.

The evidence that their six-year-old needed a more wholesome object of loyalty than Nazi parades intensified the family's impatience with life in Germany. Hitler's first territorial excursion into the Rheinland had not met any of the predicted resistance from France or Britain. The cosmopolitan merriment surrounding the Olympics in Berlin had brought no relief to Jews in the provinces. Opa Isaak and Mutti's parents in nearby Gera urged us to flee, confident that they themselves could survive in obscure retirement. First Papa and finally Mutti agreed. But they would not flee in panic, running like some other Jews over borders by night. They built a new structure of hope on the assumption that they could still escape with dignity.

Max Frankel with Leo Katz and Yitzhak - 1937.

With the deteriorating situation, the family made plans to emigrate.

Pop was hefty and athletic but, approaching thirty-five, too old to qualify, as a "youth settler" in Palestine; besides, the only thing he could reliably settle was a bad debt. He had been a peddler and storekeeper all his life. Wit and calculation were his only professional skills. Inside his chunky frame there coexisted a restless vigor and a scrupulous wile, an impulse to command and a desire to conform. Pop habitually threw himself into a battle of wits against overpowering authority, yet he submitted deferentially to the lowliest of its agents. These were qualities that might have made him an intellectual, and they certainly combined to help him outlive two tyrannies. But he was not a farmer or frontiersman.

Mom, in any case, did not want to sit in some Arab village plucking chickens, as she put it. She had been what we call a sheltered girl, an only child, plump, pretty, and spoiled, trained to observe events more than to act in them, and to imitate her mother's habit of distilling epigrammatic wisdom from her observations. A half century later she could have been a journalist. Endurance was her strong suit; confrontation pained her. She almost always retreated from combat and appeased combatants, unafraid to be considered meek, which she was not. She vowed to endure the Nazis long enough, she said, to plan an "orderly" flight. Refugees in search of a haven are about as rational as young people seeking a mate.

We were "Poles," and we assumed we could go to Poland. But Jews in Poland, while by no means hounded as efficiently as in Germany, were being widely blamed for that country's stagnant economy and unstable government. Our relatives there wrote that they would welcome a Hitler for a time, that subsisting on welfare in the German manner was probably preferable to a normal Polish existence. Our rejection of Poland felt good, too, because it preserved the illusion that we had a choice of destinations.

Our Polish passports would have permitted migration to Italy, at least to await something better, but we didn't know that; it was one of the few intricacies of migratory law that escaped us. (After World War I, as Austria-Hungary was being dismembered into Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, et cetera, my grandparents could have chosen Austrian citizenship and then qualified easily for the "Austrian quota" of the United States, but they hadn't known about that or imagined that it would ever matter.) Belgium, Holland, and France rejected all immigrant applications, though they did not turn back the refugees who crept across their borders by night. Some people argued that life in a Belgian, Dutch, or French jail was clearly preferable to freedom in Nazi Germany, but Papa thought the odds that he, Mutti, and I could safely smuggle ourselves through those well-patrolled frontiers were slim. Britain admitted only domestic servants with a firm promise of a position or industrialists with plainly desirable talents and capital. Mom and Pop felt they could not qualify, as a maid-and-butler team to some Anglican lord.

Australia seemed so far away its merits were difficult to discern. Canada required the posting of a bond–that we would not become public charges–from Canadian relatives that we did not have. There was no real objection to several Latin American countries that offered asylum, but neither was there any particular attraction. If people we knew were headed for Cuba or Brazil, we might have joined them. But no one was.

The family concluded that America their would be their destination. Getting a visa would prove more complicated than expected.

The best place, clearly, was the United States, specifically New York–so clearly that it felt like the only right place. The three most famous symbols of America for every European–Franklin Roosevelt, Fiorello La Guardia, and Columbia University–were New York institutions. Millions of Jews lived in New York and, it was said, were unafraid to speak Yiddish, not just in the streets but even on the radio! How that news delighted us. Papa had visions of muddling through with his Yiddish while he established himself in the same Jewish retail circles in which he felt so comfortable in Leipzig and Berlin. Ever the prudent realist, he also purchased a set of language books called One Thousand Words of English, whose cover bore an illustration of one man asking another, "Pardon me, can you tell me the way to the Stock Exchange?"

We would go to America.

The rituals by which America, the nation of refugees, screened other refugees were, politely put, complicated. The procedures seemed to us to be built on the premise that to help others in distress was to confer a privilege upon the undeserving. And indeed, the rules were designed to hold down the influx of ethnic undesirables and to favor the national and racial tribes living in the United States, not in 1936 but back in 1920.

The total number of immigrants admitted by the United States each year was fixed by Congress, and that number was apportioned among different nationality groups in the same proportion as the ancestral lineages of the country's 1920 population. The annual supply of visas, therefore, was distributed not in response to demand or need but by nationality quotas–so many for Britons, so many for Greeks, and oh so few for Poles. If in any year there happened to be too few British applicants but a surplus of Greeks, that was too bad; the quotas were not transferable. Nor could the applicants change their qualifications by changing citizenship; in the eyes of the United States, as in Hitler's, my parents were Poles because they were born in what had since become Poland. I was "Polish" by inheritance but German by birth; had I been twenty-one and held my own passport or had the United States wanted to admit a parentless child, I would have qualified for the much larger German quota. The system was logical, if not sensible or generous.

The United States also required a sponsor for each immigrant family, an American citizen who promised to keep the newcomers off the relief rolls. The sponsor had to demonstrate a capacity to honor this promise and a close enough kinship to make it credible. Until adolescence, I never knew that the word affidavit meant something more than the sworn statement of such a sponsor, although we informally referred to the required affidavits as the Papers.

Mutti had two cousins in New York who seemed to be the only possible sponsors. One was Felix Pfeffer, a brooding and remote man who had deserted from the Austro-Hungarian army before World War I and wandered to America, where he became rich. He owned textile mills and apartment houses and contributed large sums to Zionist causes. He kept aloof from most of the family, but he had successfully sponsored dozens of people for immigration to America, many of them virtual strangers.

The other available cousin was his distant relative Pauline Pfeffer, whose married name we didn't even know. She was the daughter of a well-known Yiddish journalist who had edited a big New York paper and, we reasoned, must have married well. Indeed she had, we discovered; although the Depression had not been kind to her husband, Victor Schwebel, he was the sort of man who would run to the ends of the Earth to help a person in distress.

We did not really need the promise of much financial aid. Pop had moved some money out of Germany to Poland and to America, of which about $3,000 remained at the end of the smugglers' discount trail in a New York bank. But we could hardly risk disclosing this illegal stash in correspondence with our relatives or applications to the American embassy.

The Papers came on Friday, March 11, 1938. I remember the date because it was also the day that, for the first time in my brief experience as a geographer, an entire nation disappeared. Cousin Felix's listed income was impressive, and Cousin Victor's promises added weight to the dossier. Friends came to share a festive Sabbath dinner, and our high spirits almost caused us to forget to turn on the shortwave radio. There had been rumors about momentous events in Austria, and Pop wanted to get the true version; so he sealed the windows, drew the drapes, moved chairs close to the console, and faintly tuned in the forbidden transmission of Radio Vienna. He did so just in time to hear a man deliver a weeping farewell address. "Gott schutze Osterreich!"–God Protect Austria!, Chancellor Schuschnigg was saying. And then they played "Deutschland uber Alles," the Haydn quartet and German anthem that Pop hastily explained was a piece of music belonging to all people and happened to be Austria's anthem, too. Pop switched the dial to a German station, which played a military, march and announced the "liberation" of Austria, leaving me to wonder whether the Austrian flag now had to be torn out of my Olympics album.

The pace of arrests in Germany quickened, and almost any scoundrel could get a Jew arrested by claiming that she had been overcharged in the store (which she should not have been patronizing) or had overheard us telling an anti-Nazi joke. So the family's only thought now was to get out. Our daily expectation was a letter from the United States consulate in Berlin promising a visa to the promised land.

When the letter came, it said the Papers were no good. Cousin Victor's income wasn't large enough to support us, and Cousin Felix's large claims were insufficiently buttressed to be believed. The consul would be happy to receive additional evidence. Incidentally, the letter added, the Polish quota was now oversubscribed and closed for several years–but our application had come just in time to make it onto the end of the waiting list.

Whatever mistake had been made in composing our relatives' affidavits, we were sure, could be swiftly corrected. We besieged New York with telegraphed requests for further evidence of our cousins' wealth, for tax returns, more papers, more promises, more of everything. But we still had no doubt of the outcome. Papa refused to jeopardize our chances by offering bribes to the allegedly susceptible flunkies at the American consulate. He also passed up visas to Latin America, now openly for sale.

No one expected what became new months of delay. Cousin Felix responded not with his tax returns but with warnings that life was tough in America and were we sure we really wanted to come? Next he wrote that he heard the Polish quota was closed and that more evidence from him would not help. We could only speculate about his hesitations; maybe people he had sponsored were becoming a burden; maybe some legal problems prevented disclosure of his tax returns. Not until Willy Gottfried, an old friend who had received an American visa with much less impressive financial backing, reached New York could we safely reveal our secret New York bank account and urge urgency upon our possibly burdened relatives.

1938: A few months before October 29, 1938, Mary and Max went to Sokal for a short trip. There they met with an uncle, presumably Leibisch Katz.

To enhance our chances, Mom and I rushed to a "vacation" in Poland to learn the names of still more remote cousins in America. This was truly a voyage back to where we had come from: the village of Sokal, whose muddy lanes resembled the storied streets of Sholom Aleichem and the paintings of Marc Chagall. Like characters in one such story, we encountered an uncle who'd never forgotten or forgiven his quarrel with Opa and therefore refused to divulge the New York addresses that we craved. But we eventually came by the names and, returning home, fired off another round of pleading letters.

It was only a half century later that I learned the true source of our difficulty. State Department archives revealed that even world-famous applicants were being turned away in response to Washington's orders "to require additional evidence and to resort to various administrative devices which would postpone and postpone and postpone the granting of visas."

Willy Gottfried's arrival in New York and Cousin Victor's energetic response to our predicament finally produced a breakthrough. They formed a Committee to Get the Frankels Out and drew up new Papers galore, and their augmented dossier reached the American consulate in Berlin on November 1, 1938–just a few hours after we were arrested and kicked out of Germany.

Mary's parents, Mathes and Margule were rounded up during the Polenaktion on Thursday October 27th, 1938, and were deported to Poland.

Max Frankel, p 17:

"...A few ... slipped through the net because, like Isaak Frankel, they were traveling on roundup day. And a good number, like Mary's parents in Gera, were deported in relative comfort, aboard passenger trains..."

After being deported to Poland, they went to Krakow, where Jakob had "...long ago smuggled some of his money, and where we could live with a relative, Uncle Isaak Pfeffer, the chocolate maker...)(Max Frankel, p 24)

Max Frankel (2013):

The "Polish" Jews from our town [Weißenfels], and many others, were imprisoned overnight in Halle, Germany, and then literally dumped on the Polish border, where we spent rainy and frightening nights on No-Man's land until the Polish government was finally persuaded to admit us all destined for "camps" in the East.

Our family was pulled off the eastward train in Krakow by Israel Pfeffer, my mother's uncle and the wealthy owner of a chocolate factory. He heard of our fate and bought "visitor" passes to the railroad platform, as was customary in Europe, and so we passed through the checkpoints and into Krakow.

We lived with him and his wife, Rudya Pipes, and their two sons until my mother and I returned to Germany on July 31, 1939, and until my father, Jacob, fled eastward when the Germans invaded Poland on Sept. 1, 1939.

I do not remember Frieda's presence in Krakow, nor do I know where they lived or how they got to the city. Nor do I remember my own grandparents (Mates and Margule) in Krakow, though I know my mother found them there in late 1939. So I suspect Leo and Frida and Mates and Margule and others who were departed by "comfortable" train actually went to eastern Poland and only gradually found their way back west, to Krakow.

Max Frankel, p 31:

"...The Jews in Krakow stumbled around the city with large yellow stars... For what she knew was the last time, Mary hugged her mother goodbye..."

Among the Jews who now lived in Krakow were Max's grandmother, Margule, and Leo and Frida Katz. They would later be moved to Tuchow and vanished, most likely murdered in Belzec in late 1942.

1940: Mary and Max emigrated to the USA. They left from Berlin and spent three days in Holland, from where they boarded a Dutch ship to New York. Jacob, who had gone to Lwow, was arrested and imprisoned by the Soviets and would be trapped in Russia for the duration of the war.

Max Frankel, p 11, 12:

(Mary KATZ) "...had two cousins in New York.... One was Felix Pfeffer... who had deserted the Austro-Hungarian army before WWI and wandered to America where he became rich.

The other was his distant relative Pauline Pfeffer, the daughter of a well known Yiddish journalist who had edited a big New York paper, and whose married name we didn't even know...

- Special Thanks:

- Max Frankel, email correspondence, 2013.

- Bibliography:

- The Times of My Life and My Life with The Times. Random House, 1999

- Juden in Gera vol II. Publisher: Hartung-Gorre Verlag Konstanz, 1998

- Juden in Gera vol III. Publisher: Hartung-Gorre Verlag Konstanz, 2000