Uriel Abraham

Name variation: Uly

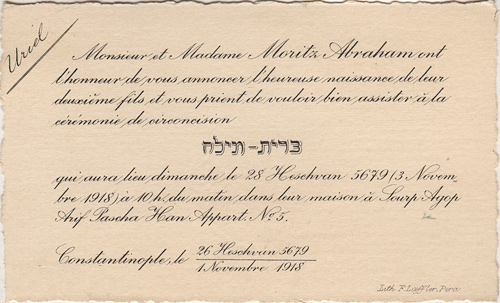

1918 - 1919 - Constantinople

Uriel Abraham was born 26 October 1918 in Constantinople, the second son of Moritz and Ronya Abraham.

Four days later, the defeated Ottoman Empire signed the Armistice, marking the end of its participation in WW1. Constantinople was occupied by combined British, French, Italian, and Greek forces.

Although born in Constantinople, he was not a Turkish national, and never felt any connections with Turkey beyond a detail on his birth certificate. His father came from Bulgaria, his mother from Latvia, and he would settle in Germany at the age of three, before coming to France in his early teens.

Birth - Brith Milah announcement, 1918.

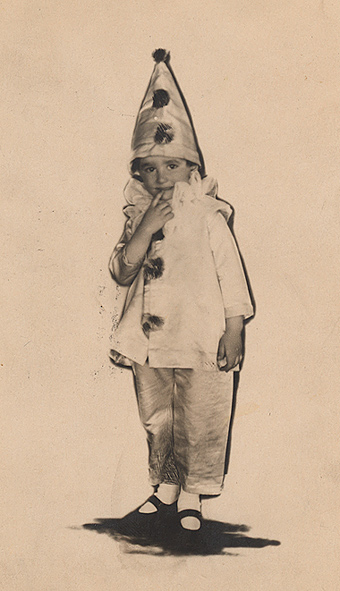

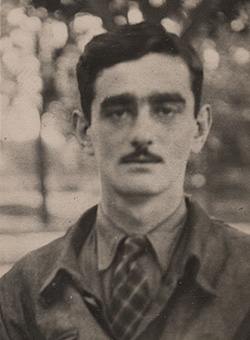

Uriel Abraham, 1919.

Gisy (with bow), Ronya and Uriel, Constantinople, 1919.

The fashion of the day was to dress up boys like little girls... So Gisy, Uriel's older brother wears a dress and a bow in his hair.

Uriel's childhood seems to have been a combination of material comfort and little parental warmth or presence.

The actual child-raising duties were handled by a nurse, Kitza in Turkey, then Frau Ewald in Germany, as Uriel's mother Ronya had other interests than handling babies - probably the norm for women in her world.

As for his father Moritz, he often travelled for business. Once the family moved to Düsseldorf, he would be away from home six months out of the year.

1920 - Berlin, Venice, Kolberg

Uriel started travelling at a young age. In 1920 alone, he went with his brother Gisy, his mother Ronya and their nurse Kitza to Berlin, Venice, Kolberg in the Baltics.

I'm assuming that the trips to Berlin were to see Ronya's sister Bertha, who lived there with Israel Auerbach and Lea.

Gisy, Ronya and Uriel, Berlin, 1920.

A year later, it's now Uriel's turn to be dressed up like a girl...

The nanny Kitza, Uriel (with the bow), Ronya, Gisy. Venice, Italy, 1920.

Maybe while on their way to Berlin, Ronya and the children stopped in Italy for a short visit?

Uriel (dressed as a girl), Kitza the nanny and Gisy. Studio portrait, Kolberg, 1920.

Gisy, Isy Mallah, Uriel and Uriel's nanny Kitza - On the beach, Kolberg, 1920.

This is an actual beach photo. But the children (especially Gisy) are wearing heavy shoes and a suit...

The Datnowsky sisters seemed to have been close, apparently spending summer vacations together in various resorts on the Baltic, from which the Abraham brothers seemed to have been absent.

Here, in the Kolberg resort, Uriel and Isy posed with their cousins Isy and Gadi Mallah, with their nurse Kitza.

1922 - Constantinople

Uriel - Purim, Constantinople, 1922.

Back in Constantinople? Or ar the dates wrong?

1922 - Berlin

In early 1922, Uriel left Istanbul and moved to Germany with his brother and mother.

They would eventually reside in Düsseldorf, in a house built on the empty lot that had been bought on LindenmannStrasse, across from St Pauluskirche.

Until the house was ready for them to move in, Uriel, Gisy, Ronya and the nanny - Frau Ewald - lived in Frau Brockerhoff's boarding house, a guest house popular with artists and intellectuals in Düsseldorf.

They apparently also went to Berlin - maybe to see Bertha who might have moved back to Berlin by then?

Uriel in Berlin, 1922.

The family also went to Thuringia the same year - although the reason why is not clear.

1922 - Thuringia

X, Ascher Mallah, nurse, Gisy, Elfriede (?), Uly, head nurse, X, Ronya (sitting), Bertha. Thuringia, 1922.

This seems to be a sanatorium - who was hospitalized? Gisy? or Isy's older brother? The extended family seems to be here: Medi is Mony Abraham's wife, Grischa is a cousin of Ronya, I don't know who Tania is, Ascher Mallah is Eva (Liska)'s husband.

Front row: Medi, Tania (?), Ascher Mallah, Bertha.

Back row: Grischa Datnowsky, Gisy, Uly, Lea, Ronya.

Thuringia, 1922.

Uly and Gisy, Thuringia, 1922.

Gisy and Uly, Thuringia, 1922.

1923 - Godesberg

Uriel, Isy (Alex) Mallah, Liska (Eva) and Gisy. Godesberg, 1923.

Another vacation with the family, this time in Godesberg, with his cousin Isy Mallah.

1924 - Düsseldorf

My father mentioned that their nurse would take them to play in the church yard next to the house, but it was a secret and she wouldn't tell their parents.

From 1924 to 1928, Uriel atented the VolksSchule (elementary school) on BrehmStrasse in Düsseldorf.

VolksSchule, BrehmStrasse Düsseldorf, ca 1924.

On this school photo ca 1925, Uriel is one of the rare children without blond hair.

Gisy, Reni (adopted daughter of Mony and Medi Abraham) and Uriel. Düsseldorf, 1924.

1925 - Berlin

Uriel, Ronya and Gisy. Germany, 1925.

1925 - Düsseldorf

Uriel, Gisy and their short-lived dog. Düsseldorf, 1925.

Uriel, Purim. Düsseldorf, 1925

The family maintained some Jewish traditions, as this Purim photo shows, but as a whole the family was probably very secular.

Uriel and Gisy, Adelboden - Switzerland, 1926

Ronya and the children went on vacation - skiing in Switzerland in the winter, to various Baltic resorts in the summer.

1927: Postcard from Godesberg.

1928

Around 1928, Uriel was tutored in Hebrew by Dora Diamant. Best remembered as Franz Kafka's lover, she was a struggling actress and was studied acting in Düsseldorf.

Uriel mentioned that she had been his private Hebrew tutor, I assume to prepare for his bar-mitzvah. He recalled that his mother supported her financially.

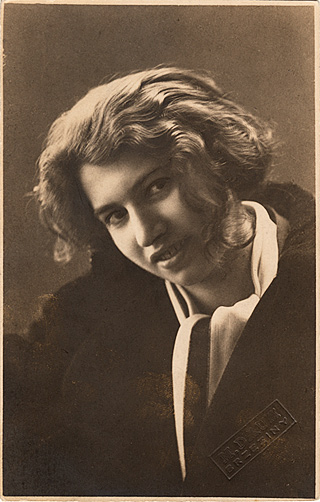

Dora Diamant, Düsseldorf, 1928

This photo was given to Uriel's mother Ronya. Uriel's caption reads:

"Dora Diamant - Düsseldorf 1928

Companion until his death of Franz Kafka.

Actor student at "Schauspielhaus" in Düsseldorf.

Protégée of Ronya Abraham.

Gave Hebrew lessons to Uriel."

1929

Uriel and Gisy, Celerina Grisons - Switzerland, 1929

Uriel and Gisy, Henkenhagen - Baltic, 1929

1929 is the last year for which there are vacation pictures.

1929 is also when Uriel (and his brother Gisy) started to go to a school in Berlin. Was it a boarding school? Was he staying with Bertha? Or had the family moved to Berlin?

Did this correspond to the beginning of financial problems?

Berlin, 1929 - 1930

Uriel, Goetheschule, Berlin, 1930

Uriel is second from the right in the front row.

Some of the children's names: Horowitz, Teppich, Heymann, Arendt, Berliner, Soskin, Mayer, Minz, Wachsman... The other half of the boys have blond hair and wear lederhosen.

Düsseldorf, 1930

Uriel and Gisy, Düsseldorf, 1930

On this photo, Uriel is back in Düsseldorf with his brother. Maybe they were still based in Düsseldorf, but had gone to a boarding school in Berlin - or attended a boarding school in Berlin but came back to Düsseldorf for vacations?

Changes

The story as told by my mother is that one day, Moritz came home saying "it's over, it's all gone" - apparently all the money had been in the stock market (or paper) and his fortune was wiped out instantly.

I suppose things had to be more complicated - for example, was the company Abraham Freres not operating anymore? or struggling?

Regardless of the exact circumstances, it seems that it was the end of an era for the family - not only would their former lifestyle become a thing of the past, they would soon leave Düsseldorf and move to Paris.

The connection between the fortune reversal and the move to Paris is not clear. Probably the best explanation is that Ronya's sister Bertha lived there and could offer some help.

Paris

Uriel was eleven years old when he left Düsseldorf and came to Paris. The move was a big change - not only did he come into a new world, he also traded the life of wealth he had known since childhood for a more restrained lifestyle. At one time his mother had been extravagant enough to employ five servants in their house, now the family would be living in several small sublets.

Uriel had apparently learned French in Germany, he seemed to be perfectly fluent soon after being in Paris.

At first, the family seemed to move to live in different places, although always in the 16th arrondissement: rue des marronniers, Bld Exelmans, then rue Erlanger. These were probably sublets.

Uriel, Lycee Lakanal, 1931-1932. Second row, right.

Uriel attended the Lycee Lakanal boarding school of Sceaux between 1930 and the summer of 1932, in the southern suburbs of Paris. Was he sent there because many foreign and emigre students also did? Or was it simply more convenient to have him be in a boarding school?

There were a number of immigrant students - Vietnamese, Germans, and in particular White Russians who had escaped the Soviet revolution.

One boy told of the violence and the misery of the red revolution, repeating stories of desperate populations turning to cannibalism out of starvation, and Uriel who was sympathetic to the Socialist party SFIO accused the boy of being a liar. Many years later he realized the boy was telling the truth and he still felt guilty of having refused to listen to him.

Around 1931, Uriel did his bar-mitzvah. He told the story of how his mother had taken him to the big department store to get a costume for the ceremony, costume she returned afterwards...

In April 1932, the family moved once again, this time boulevard murat, still in Paris 16th.

Uriel, Lycee Janson de Sailly, 1934-1935

In Janson de Sailly, classe de 2eme B. A large number of the boys have foreign names, many Russian or Jewish.

Uriel's grades are excellent - out of a class of 40 students, his worst subject is French (9th out of 40), otherwise he has the 1st place in history, 2nd place in German, English and Math, and 3rd in Physics and Chemistry.

Gisy

In July 1934, Gisy, Uriel's brother, disappeared while hiking in the Alps. He was seventeen years old. Uriel was very affected by the loss, and never talked about what happened, or even mentioned his brother's name.

In the fall of 1934, Alex (Isy) Mallat was sent by his parents from Salonika to study in Paris. He went to Janson and stayed with Uriel over the weekends.

At the end of 1935, the family's address changes once again, they are back rue des Marronniers - probably subletting an apartment that belonged to a relative (Ascher Mallah?)

According to Alex Mallat, it was a "charming apartment, with a back door opening to rue des vignes."

In 1937, Uriel receives his baccalaureate ("Bac B-Philo mention")

His mother Ronya encourages him to pursue a career in graphic design, thinking it would be a good career for him, or simply believing that he has a "natural ability" for it.

In 1938, he became a student in l'Ecole Paul Colin, where he would study until Spring 1939.

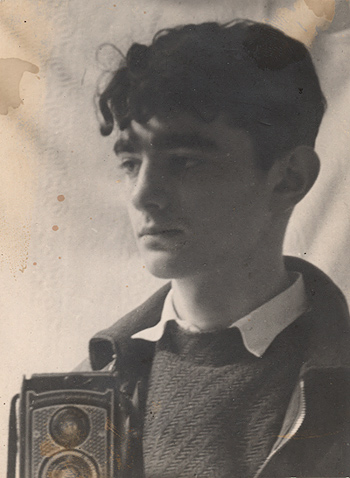

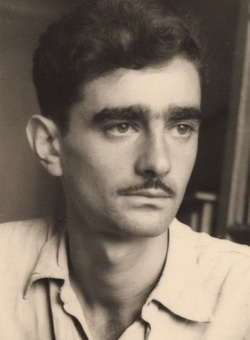

Uriel, self-portrait, 1935-1938

Uriel also studied photography, taking classes with Josef Breitenbach, and working in his studio and lab, shooting, and doing processing and printing work. His involvement with Breitenbach dates from at least 1935, as a print of a Breitenbach photo is inscribed "My Lieben Abraham, 3 Oktober 1935."

Uriel, 1936-1939

In the fall (or winter?) 1939, the family moved once more, this time Rue de Lubeck - as always in the 16th Arrondissement.

In November, Uriel was found eligible to join the French Army, but was not drafted. (However he still held a Spanish passport - Were foreigners called into the French army? Wouldn't he have been drafted with the Foreign Legion?)

Indeed, in December, he requests an National ID card which allows him to reside in France as a student, but not hold any occupation, as he is a resident alien.

WWII

In May 1940, Germany invaded France.

Uriel recalled that, after the German invasion, he went to the army barracks in Paris, hoping to enlist. The soldier on guard told him that the army had been "redeployed". When he asked where to, and where should one go to enroll, the soldier replied he had no clue. Uriel said that "right then, knowing the Germans and their efficiency, I saw that it was over, France had lost the war."

He went home and told his parents the family needed to leave Paris immediately, but they refused to leave, and he decided to flee alone.

On June 3, 1940, the Germans bombed Paris. An estimated six to eight million people, including half the population from Paris, took to the roads in a mass exodus. By foot, in wagons, pushcarts, cars or trucks, they tried to flee the advancing German army. On June 14, German troops marched into Paris.

Uriel said he fled on a bicycle, and that getting to the South of France only took him "a few days". After reachin the Mediterranean coast, he tried to find a ship to go to England. Along with a few other people he had met on the harbor (in Marseille? or Nice?), he tried to find a place aboard a vessel that would take him, but found that the rare spots were given to high-ranking members of the army or the government, the nucleus of the future Free French.

Running out of options, he finally resigned himself to boarding any ship that would take him, regardless of its destination. Eventually, a ship sailing to Casablanca materialized. Feeling he was running out of time, Uriel boarded that vessel in late June or early July 1940 en route to Morroco .

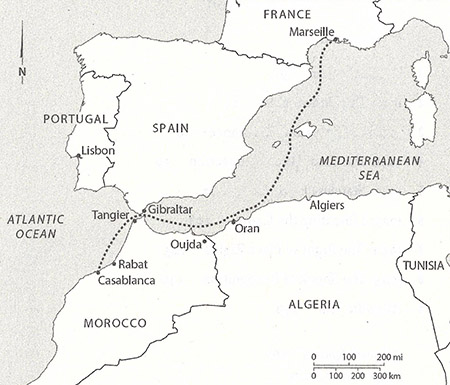

Casablanca 1940 - 1944

The route from Marseille to Casablanca

(Source: Susan G. Miller,

Days of Glory: Nelly Benatar and the Pursuit of Justice in Wartime North Africa,

(Stanford, CA; Stanford University Press, 2021)

The trip from Marseille to Casablanca lasted a few days, and Uriel arrived in Casablanca sometime in July 1940.

Upon landing, he must have experienced the disorientation of being in a foreign locale very different from Paris or Düsseldorf, and under unique circumstances. With the recent influx of over a thousand refugees in the two weeks since the Germans had entered Paris, Casablanca had become "a small Tower of Babel". In the first week of July, 1940, there were 30 ships packed with refugees from Europe tied up in the Casablanca harbor, their passengers unable to disembark for days, suffering from the heat and lack of food and water.

On July 19th, Uriel sent a brief postcard to his parents: "Write to me P.O. Box, Casablanca."

A newly formed Committee of Assistance to Refugees, led by Nelly Benatar, helped refugees find lodging, food and other necessities, and local Jewish families volunteered to take refugees into their homes. I don't know if Uriel relied on the Committee, or if he was able to find accommodations on his own.

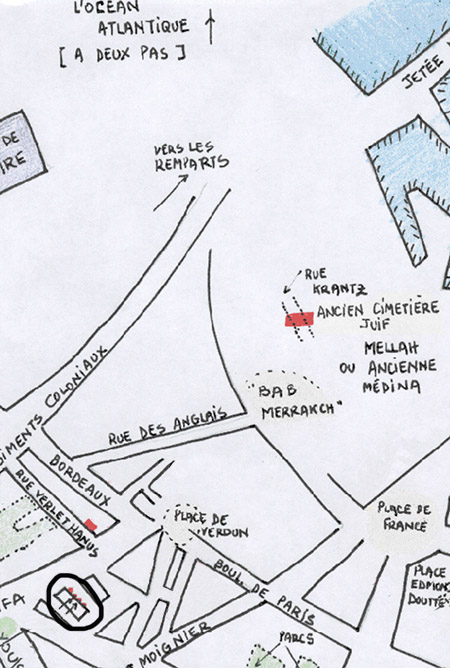

Uriel found a place to stay with the David and Marie Benaim, a Jewish family who lived 2, rue de l'Oise. There he occupied a small room on the first floor. (Another address is given as 4, rue de l'Oise; It's not clear if this was a mistake, or if he indeed stayed in both locations at different times. According to their grandson, there was indeed another house at the end of the street occupied by David Benaim's brother. It is thus possible that my father stayed at the addresses.)

Rue de l'Oise (now Rue Abou Hassan Al Achaari) was a small street close to the Mellah - the old Jewish quarter. Although situated outside of the Mellah, the area was undeniably Jewish. According to David Benaim, grandson of the family who hosted my father, "Only Jewish families lived on the street, such as the BenZohar families and the BenHarosh family". He adds: "(The Benaims were) a bit of a different class, all of the Benaim brothers lived in a slightly better area (than the mellah)." On the corner at the end of the street was a small synagogue, Synagogue Bennaroch, while on the opposite side, across Boulevard Anfa, was Temple Beth-El, Casablanca's largest synagogue.

2 rue de l'Oise and surroundings

(Source: David Benaim)

Former Benaim house, 2 rue de l'Oise.

(Photo courtesy of David Benaim)

David Benaim (David and Marie's grandson) (2009):

"(My father's) little sister Flora (born 1935) remembers your father. She remembers that he lived in one of the rooms in their home, he had a friend (she doesn't remember his name) who lived not far. She doesn't remember where he came from, or why, or what he did there, she was 5-9 years old. Uriel lived the first floor, in a little room."

In September, Uriel received a letter of recommendation from famed photographer Josef Breitenbach, certifying that Uriel had taken photography classes with him and had worked in his studio and lab. This suggests that, six weeks after his arrival, Uriel was planning to remain in Casablanca and was looking for photography-related employment, whereas for most of the Jewish refugees, Casablanca was only intended as a stop on the way to Portugal, then to the USA or Southern America.

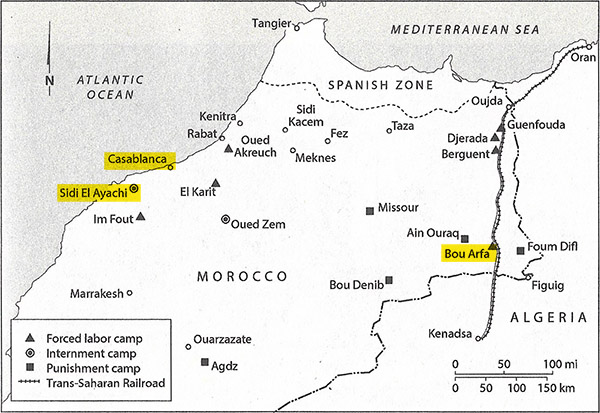

Sidi El Ayachi and Bou Arfa (Bouarfa)

On 27 September, 1940, the French Government passed a law establishing Foreign Laborer Groups ("Groupements de Travailleurs Etrangers", known as GTE), as a means to separate "foreigners overcrowding the national economy" ("les étrangers en surnombre dans l’économie nationale")), thus allowing the internment of refugees into forced labor camps. The refugees targeted by this measure were the 400 000 Spaniards who had fled their country after the victory of Franco, and almost the same number of Jewish or political refugees from Germany and Austria. This was followed soon on October 4 by a decree relative to the incarceration of foreign Jews into internment camps.

The newly-created GTEs were placed under the authority of the Department of Labor and Industry (("Ministère de la production industrielle et du travail")), and aimed to combine two goals: support the so-called "National Revolution" ideology of the Vichy authorities by removing from civil life refugees viewed as "undesirable foreigners", while providing cheap labor for mining work and large construction projects of crucial importance to the French economy.

The French authorities in Morocco, in line with the French Government in Vichy, viewed the mass of refugees who had recently arrived in Morocco with suspicion - former Spanish Republican fighters and volunteers of the International Brigades, German and Austrian Nazi opponents, members of the French Legion - foreigners who had enrolled to defend France against the German invasion, anti-fascists, Communists, Socialists, Gaullists, and European Jews who had fled Europe.

Although anti-Jewish measures were promulgated against Morrocan Jews starting October 31, 1940 by Sultan Mohammed Ben Youssef under the pressure of the Vichy Government (Resident General Noguès), these measures were not as wide-ranging as those in effect in German-occupied Europe. While they established a numerus clausus for liberal professions, restricted access to secondary schools, institued a census and put Jewish property under gardianship, indigeneous Jews were not targeted for deportation or extermination. Unlike in occupied Europe, Morrocan Jews did not have to hide and were able to remain in place, explaining how Uriel was able to find a place to live - and later to hide - in a Jewish home.

On October 3, 1940, the law establishing the GTE was extended to also apply to the French North Africa. And so, in October, Uriel was arrested by "la Police Speciale de Casablanca". As a foreign Jewish refugee holding a Spanish passport, he was a prime target for the Vichy police. His holding a Spanish passport made him suspect in the eyes of the authorities, as any man of fighting age with such passport was suspected of having been an anti-fascist figther of the Spanish Republican army.

About ten camps existed in Morroco and would hold about 7000 people, 30% of them foreign Jews.

Internment and Labor Camps, Morocco

(Source: Susan G. Miller,

Days of Glory: Nelly Benatar and the Pursuit of Justice in Wartime North Africa, p.95

(Stanford, CA; Stanford University Press, 2021)

Uriel was first incarcerated in Sidi El Ayachi, an internment camp for foreigners.

In December, he was then sent from there to Bou Arfa, about 800 kilometers (500 miles) away.

Bou Arfa was the largest labor camp in Morocco, located on the edge of the Sahara desert, fifty kilometer from the Algerian border. Located in a mining area (manganese), next to a train line, Bou Arfa was a launching pad for the Trans-Saharan train line. Prisoners interned in the camp worked repairing the existing train line, and built the next section of the Trans-Saharan railway - leveling dunes, clearings rocks, laying tracks.

In July 1942, a Red Cross report would count 818 inmates in Bou Arfa, 694 Spaniards and 124 from sixteen nationalities or “stateless” - anti-fascists and European Jews.

Forced Labor camps of Sahara, 1941-1942

(Source: Martin Gilbertm The Routledge Atlas of the Holocaust)

Uriel was incarcerated with the "9ème Compagnie de Travailleurs Etrangers." This affiliation seems to confirm that he was arrested primarily because he held a Spanish passport, and was thus suspect of being a former Republican fighter, since the CTEs and GTEs were mainly made up of former Spanish refugees.

Conditions in the camps are often described as having been extremely harsh for the labor conscripts working on the railroad, with some describing Bou Arfa as "one of the worst camps." However, according to Uriel, the camp was "nothing at all like the German concentration camps in Europe".

Uriel, a man of few words, was notoriously discreet and refused to sound heroic. It would have been very much in his character to minimize what he had gone through. He probably didn't want to dwell on his incarceration and "traumatize" his children.

Uriel believed that the rounding up of refugees had actually been more of a preventative measure designed by Sultan Mohammed V to protect Jews: by incarcerating them, he was removing the excuse for Vichy to implement harsher measures, such as deportation to Europe.

Although Mohammed V did help shield Morrocan Jews from antisemtic measures, it's not clear how much power he could really exercise to protect the refugees, as the internment camps did not fall under his control, but were under the exclusive control of the French army.

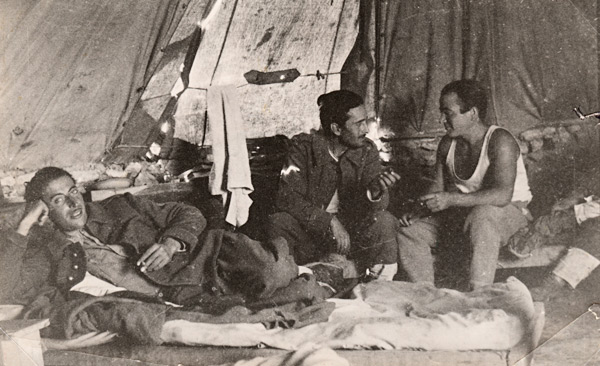

Bou Arfa, 1941: Fernando Zambrana from Seville, X, Antonio Sanchez from Aranjuez

My father's caption on the back of the photo said: Zambrana from Toledo, X, Y from Aranjuez

From his stay in Bou Arfa, Uriel had a single artifact: a photograph showing three men under a tent. By its mere existence, this photo is quite revealing, in addition to providing a glance at the conditions in the camp.

- The fact that a detainee could take a photo inside the camp is a clear indication that the conditions at Bou Arfa were indeed nothing like those found inside Nazi camps, where inmates were stripped of all personal belongings; indeed no photos taken by inmates of German camps exist, whereas a number of photos taken in Bou Arfa by internees can be found online.

- The most striking thing about this photograph is the relatively relaxed attitude of the men, considering they are held in a labor camp: one is lying down, holding a cigarette, the other two in friendly conversation. Although there against their will, and despite the harsh conditions reported to have been prevalent in Bou Arfa, the men look nothing like inmates from Dachau, let alone from Auschwitz.

- Another revealing detail is their clothing: instead of prisonner garbs, they are wearing what seems to be a combination of army surplus jackets and civilian clothes.

For years, the existence of this lone photo from Bou Arfa in my father's photo album puzzled me. Why did my father hold on to this photo? Who had taken it? What was his connection to the men on the picture?

If my father had been the photographer, why was this the only photo from the camp? If he had been able to bring a camera to the camp, he surely would have taken more than a single photo during his six-month stay. Is it possible that only one shot had survived? For this to have happened, he probably would have needed to be able to process and print the photo while at Bou Arfa to be able to give a print to one of the men, who would later have given him a copy.

However, if he wasn't the photographer, why have this particular picture, as opposed to a photo of himself, which would have made more sense for him to hold on to?

The fact that he had this particular photo suggests that he knew these men (or at least one of them), and probably shared a tent with them. However, based on the inscriptions on the back of the photo, he only remembered the first name of the man on the left ("Zambrana from Toledo"), the city of the man on the right ("Y from Aranjuez"), and didn't remember either the name or city of the man in the middle ("X"), indicating that they weren't very close.

Finally, I assumed that the photo had probably not been printed in Bou Arfa, believing that there was no opportunity for internees to get film developed and printed in the desert. I thought it more likely that this photo would have been enlarged later, for example in Casablanca when Uriel worked in the Pollack photo lab in late 1942 or 1943. However, these assumptions may be wrong since internees were apparently able to leave the camp, and there are now a number of photos from Bou Arfa that have surfaced online, indicating that several people had brought cameras in the camp with them.

In April 2015, the son of one of the men on this photo contacted me after having recognized the man described as "Y from Aranjuez" as his father, Antonio Sanchez from Aranjuez. He too owned a copy of the photo, which may suggest that this photo was processed at a later date, probably in Casablanca, in or after 1942. For this to happen, the man who took the photo (whether my father or a third party), Uriel and Antonio Sanchez must have been in contact and met in Casablanca after leaving Bou Arfa.

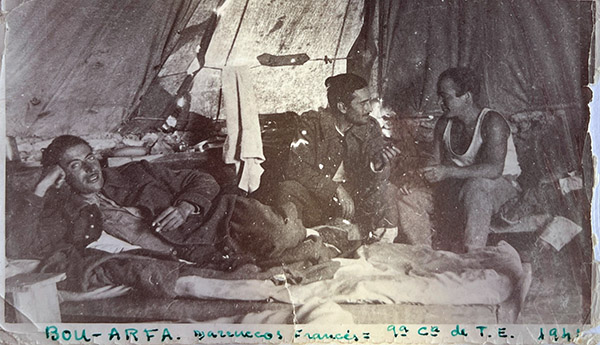

Bou Arfa, 1941: Zambrana de Toledo, X, Antonio Sanchez

(Photo courtesy of Santiago Sanchez)

Here is the other copy of the photo, this one belonging to the Sanchez family. Although quite damaged, it is uncropped and provides a more complete view of the tent. In particular, the cots are clearly visible, and one gets a better sense of the dimensions of the tent. The feet from a fourth man are visible to the right of Sanchez.

Regarding his father, here is what his son, Santiago Sanchez, had to say:

Antonio Sanchez came from Aranjuez and fought during the Spanish Civil War with the Republican Army. After the collapse of the Republicans, he left Spain and arrived in France as a political refugee in 1938. There, he was incarcerated in three different internment camps, escaping from the third one. He then made his way to Brest in the North of France where he boarded a ship for Casablanca as a stowaway in 1940. At his arrival in Morocco, he was found and immediatly arrested by the Vichy French police and interned in Bou Arfa. The camp hosted mainly former Spanish Republican fighters. In the camp, Anarchists and Communists kept to themselves. While in the camp, he worked on the construction of the railway line. He remained in the camp until its liberation by the American army in 1942. After leaving the camp, he worked for a while for the Americans as a cook.

A third copy of this photo exists, this one preserved by Fernando Zambrana's family:

Bou Arfa, 1941: Fernando Zambrana from Seville, X, Antonio Sanchez from Aranjuez

(Photo courtesy of Maricruz Zambrana Jirash)

The existence of three copies of this photograph suggests that a fourth copy probably exists, this one in the estate of the unnamed man.

It is possible that, in the beginning, life in the camp was somewhat tolerable, but that conditions later worsened; it is possible also that the concern grew that conditions would worsen - they would maybe be handed to the Germans.

Whatever the exact reasons or situation, Uriel decided to escape from the camp.

His first attempt was unsuccessful:

He had managed to get out of the camp with a fellow prisoner, a German refugee (a Nazi opponent). They hid under a train, on the axle, but after moving a little, the train stopped in the middle of the desert. Afraid they would be stuck there all night and then be discovered, they decided to sneak back into the camp.

In June 1941, his second attempt was more successful. This time he escaped on his own. My mother said:

"The security was pretty lax to say the least: the gate of the camp was open, so he just walked out without looking back or hesitating, acting confident, and that was it."

This description of a low-security labor-camp seems very strange - however online testimonies do mention that the camp was not hard to leave - the desert was supposed to be what would keep the prisoners.

After escaping from Bou Arfa, Uriel somehow made his way back to Casablanca. How he managed to get from Bou Arfa to Casablanca is a complete mystery. Bou Arfa is almost 600 kilometers (335 miles) from Casablanca as the crow flies, the actual land distance, with limited roads and railroad being much greater.

In 1943, while on a mission to inspect labor camps, it would take Nelly Benatar four days to reach Bou Arfa from Casablanca. "A strenuous trip on very bad roads" of almost a thousand kilometers, "the last two hundred kilometers on a rutted dirt track, seeing nothing but desert." (Susan G. Miller, p 109)

Ted Harris, a Bou Arfa escapee, is said to have walked across the desert for ten days to reach Spanish Moroocco (Hindley, p176). I assume that Uriel would not have chosen to cross the desert by foot. Instead, I imagine that the most obvious route would have been to take advantage of the train line to reach Oudja. From there, one could take another train all the way to Casablanca.

Bou Arfa postscript

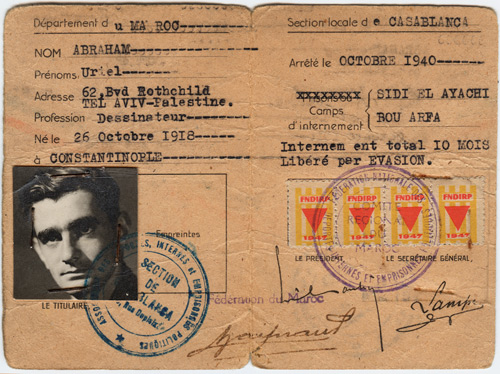

In 1947, Uriel registered with the Fédération Nationale des Déportés et Internés Résistants & Patriotes ("National Association of Deportees and Imprisoned Resistants and Patriots").

"Fédération Nationale des Déportés et Internés Résistants & Patriotes" - 1947

On his membership card, the duration of his incarcerations is given as ten months, although, having been arrested in October 1940 and having left the Bou Arfa camp in June 1941, the actual duration must have been between eight and nine months.

Right after returning to Paris in 1949, he requested a certificate from the department that had been responsible for his arrest:

Monsieur le Commissaire de la Police Spéciale, Casablanca

"(...) I would be very obliged to you if you could send me a certificate attesting that I was arrested by your services in Casablanca in October 1940 and incarcerated in Bou Arfa until June 1941, at which date I escaped from this camp. (...)"

However, in 1958, his application to be recognized as a political prisoner was turned down by the French government - he was thus denied any compensation. In 2005, almost fifty years later, Germany would finally agree to provide reparations to survivors incarcerated in labor camps in Morocco.

In Hiding

It's not clear what happened after his escape. Eventually, Uriel made his way back to Casablanca, and again lived with the same Jewish family (the Benaim) he had stayed with before his arrest.

Uriel was now hiding - a foreign Jew and an escapee from a labor camp. It seems incredible that he went back to the same location and felt it a safe enough place to be hiding with a Jewish family. Although Jewish, his landlords were still protected as Moroccan citizens.

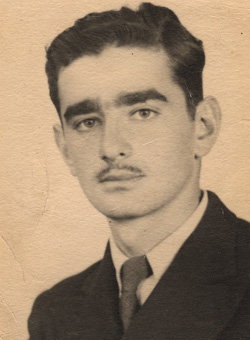

Uriel, Casablanca 1941

Uriel, Casablanca 1941

1942

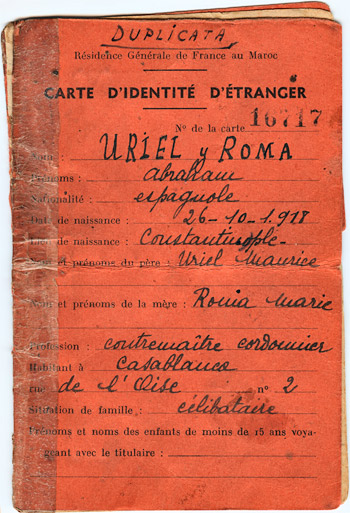

In October 1942, he acquired a Resident Alien ID card with a fake identity to dissimulate both his real name and his Jewish origins.

Fake Resident Alien ID, 1942

Last Name: Uriel Y Roma

First Name: Abraham

Father's Last and First Name: Uriel Maurice

Mother's Last and First Name: Ronia MarieProfession: cobbler foreman

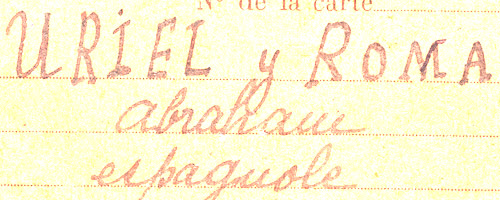

Not only was this ID using a fake name, the card itself had been tempered with - rather crudely. Close inspection of "Roma" shows that the letter "M" was retouched, and that a line had been added with a darker ink, changing "Ronia" into a more Christian "Roma".

Forged name on Resident Alien card, 1942

The forgery was rather crude and could probably be discovered if one took the time to scrutinize the document. Moreover the modified name didn't even match his mother's name as it appeared a few lines below.

On November 8, 1942, the American army landed in Morocco, entering Casablanca on November 11 (operation Torch).

The American landing however didn't put an end to Vichy's rule and its anti-Jewish laws, as "the Americans had reached an agreement with the Vichy leadership in Algiers, which gave the Anglo-American forces free passage through the French-controlled territory in exchange for continued recognition of Vichy French sovereignty over France's North African possessions." (Robert Satlof)

Arrests of Jews continued in Morocco, and racial laws were only abolished in March 1943 after the Gaullists came to power.

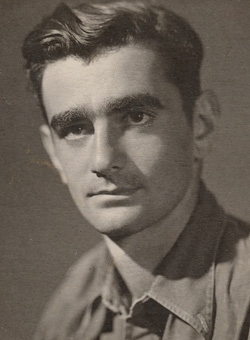

Uriel, Casablanca 1942

Uriel, Casablanca 1943

Around that time, he met a Spanish Republican who had fled from Spain after 1936 named Carmelo. Together they try to make money by manufacturing sandals out of tires...

From December 1, 1942 to December 12, 1944, Uriel worked in a photo studio - "Photo Paul, 40 rue Blaise Pascal, Casablanca", as a photo technician, doing processing, retouching and assistant work.

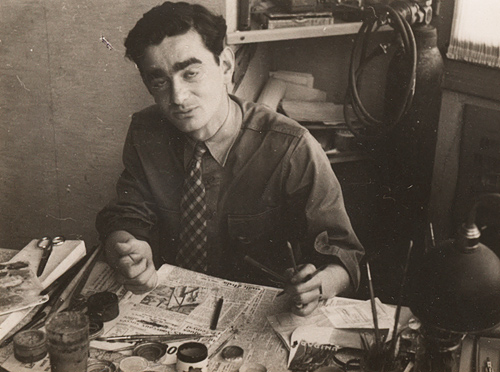

Uriel, Casablanca 1943 - Graphic designer

He also seems to have worked with Charles Gabay doing graphic design work.

Uriel once commented on the movie "Casablanca", saying it was a Hollywood fantasy which didn't show how life actually was during the war. In particular, he explained how people didn't mix - for instance, Europeans didn't mix with the local Arabs.

He didn't eat Arab food sucha couscous for instance, but instead went to little European restaurants that served French-style food - "ragouts" etc.

He said he had once tried "kif" - the tobacco and hash mix which was legal in Morocco and was sold in every tobacconist - he claimed that it didn't do anything and never tried it again.

His social circle seems to have been mostly made up of European Jewish refugees:

- Mittelmann. Dr. Maximilien Mittelmann, simply known in our family as "Mittel"), a Jew originally from Czernowitz (Austria-Hungary, now Chernivtsi, Ukraine). He lived in Paris before the war. He later moved to Nice in the South of France and remained a friend of our family until his death in Paris in 1974.

- Paul Pollack, the photographer Uriel worked with in Casablanca - a Hungarian Jew who later emigrated to Canada

- Charles "Gab" Gabay, a graphic designer - another Jew, although he may have been from Casablanca originally

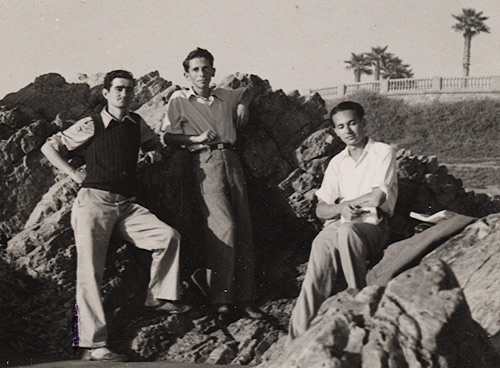

Uriel and friends: Donald X from the US army, Harosh (= Benharosh?), Paul Pollack, Mittelmann. Casablanca 1943.

Uriel, Mittelmann, Charles Gabay. Casablanca 1943.

Uriel, Charles Gabay, Mittelmann. Casablanca 1943.

Probably his only non-Jewish friend, Carmelo was a Spaniard with whom he had several business ventures. At first they made sandals from rubber tires. Later, right after the Operation Torch landing, they organized a laundry service for the American GI's, hiring local Arab women to do the wash. After the US army got settled and started to bring in their own washing machines, this business died out.

Uriel, Casablanca 1943 - "To Dear Mom"

Uriel, Casablanca 1943

1944

Uriel, Casablanca 1944 - Studio Paul

Uriel, Casablanca 1944 - Studio Paul

In February 1944, Ronya, Uriel's mother, left Spain where she had been a refugee since 1943, and came to British-controlled Palestine.

By then, although the war would still go on for another year, the end was finally in sight. With Morocco under control of the Free French, Uriel didn't need to hide anymore anymore - for him at least, the war was pretty much over.

In June 1944, Uriel made arrangements to go to Palestine, and received a safe-conduct and travel documents from the Free French and Allied military authorities.

Finally, six months later, he left Morocco. He crossed the border at Oujda on December 12, 1944, arrived in Algiers on the 16th, then, on December 23, flew from Tunis to Cairo.

Uriel, Cairo, 1944

Israel - 1944-1951

Uriel arrived in the port of Haifa on December 29, 1944. The immigration manifest listed his address as 62 Rothschild Boulevard in Tel Aviv. (This may have been the residence of his uncle, Asher and Liska Mallah. His mother, Ronya, lived in Jerusalem.)

His ID card issued by the British Authorities declared him to have green eyes (!), and of course, "Race: Jewish".

At first Uriel lived in Asher Mallah's law office in Tel-Aviv, on the edge of Jaffa.

Uriel had become friends with Alex Neuhoff, the son of a couple Ronya had met in Spain, who had come to Palestine with her on the Nyassa.

Alex Neuhoff:

"Uriel asked me if I would be interested to live in a room in a small concrete house, one floor with a terrace. The office, this little house had just two rooms, it wasn't luxurious, but it was fine - it was quiet.

The terrace was really precious because nights were incredibly hot: at night, we'd bring a mattress upstairs and we slept on the terrace, otherwise the heat was unbearable.

Around 45, 46, that's when gunfights started between Jews and Arabs - sometimes there would be gun shots during the night."

"We stayed there about a year I suppose, in the house/office of Mallah. We slept there during the night, and in the morning we had to leave, because Asher still worked there. We couldn't touch any of his stuff. We just had a bed, a sort of couch, where we slept.

Around 1945, when Greece was liberated, Asher and Liska Mallah left Tel-Aviv to return to Greece, and they said Uriel couldn't stay in the office anymore.

Afterwards, we went to live in the appartment Rehov Rothschild." (i.e. 62 Rothschild Boulevard.).

At the time, Hebrew was not required. New immigrants - like Uriel or me, spoke their own language - French, or German.

Uriel and his cousin Bitia, Talpioth

Uriel and his aunt Liska, Israel - 1947

Uriel and a friend, Zichron Yaakov, 1947

On a temporary visa application dated November 10, 1947, Uriel's address was listed as:

15 George Eliot Street, Tel Aviv

His occupation: Designer, and his nationality: Spanish.

At that time, Uriel worked for an Italian architect, Ugo Gnagnatti (Anati)

Uriel, Ronya with Elsa and Ugo Anati - 1945 or 1946

According to Alex Neuhoff:

"This man (Anati) wanted to commercialize products from Italy which had just been liberated, or almost... He wanted to import modern art objects made in Italy, and he needed someone to handle his office, he wanted someone who would have some artistic knowledge."

"Uriel was very impressed by Ugo Anati's wife - especially by how she raised her children: they were allowed to climb over the furniture and do as they pleased, which was very different from how he had been raised - he thought it was fantastic!"

So Mr Anati ran his import business a little bit the way he raised his kids, in other words it was a bit crazy, and Uriel loved that. He really admired how he did things."

Then (around 1947?) Alex introduced Uriel and Toni, who was then married to a cousin of his. (A cousin on his mother's side - Rovinski - Alex' mother's maiden name was Oistrach - related to David Oistrach.)

"They would all meet on the beach, they would play ball - that's how they met."

1948

Uriel joined the Hagannah in April 1948, one month before the begining of the war. He was apparently not sent to the front lines, but instead served in the rear designing defense shelters until the end of the hostilities in 1949.

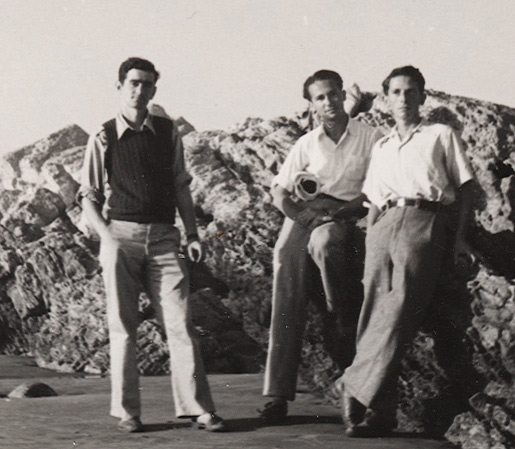

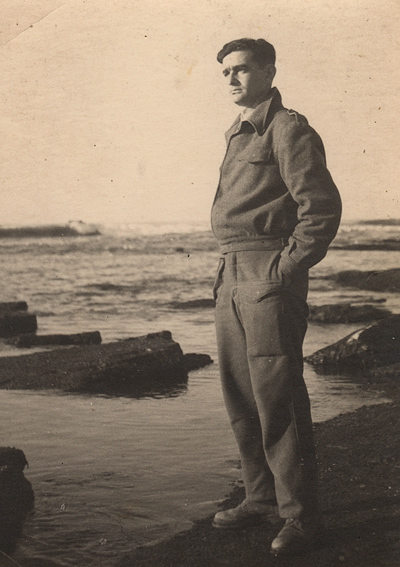

Uriel in the Hagannah - 1948

Uriel in the Hagannah - 1948

Uriel in the Hagannah - 1948

Uriel in the Hagannah - 1948

I once asked him about these photos - he said he was just playing, posing for the pictures.

Scrapbook

Hagannah - 1948

Hagannah - 1948

Hagannah - 1948

Hagannah - 1948

Hagannah - 1948

Hagannah - 1948

Hagannah - 1948

Hagannah - 1948

Hagannah - 1948

In 1948, he gave his address on a power of attorney as 36 Maimon street, c/o Dr Israel Auerbach, Jerusalem (Palestine). He also declared being a Spanish citizen - apparently he never acquired the Israeli nationality.

1949

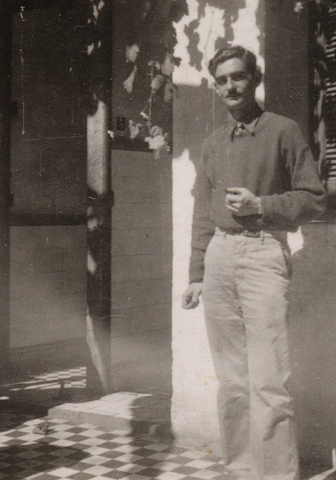

Uriel, Tel-Aviv - 1949 (photo: Toni)

After the war.

Uriel, Tel-Aviv - 1949 (photo: Toni)

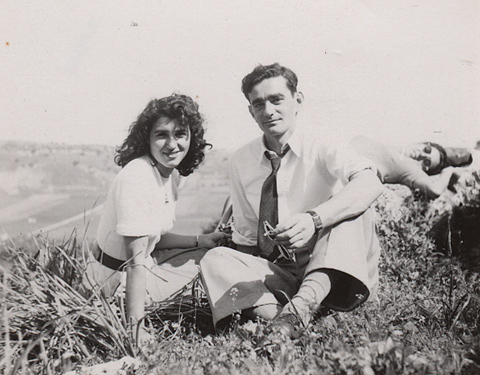

Uriel and Toni, Israel - 1948

Uriel and Toni, Israel - 1949

Paris 1950 - 1951

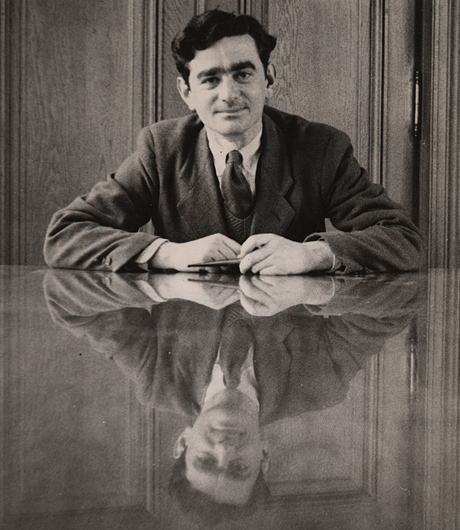

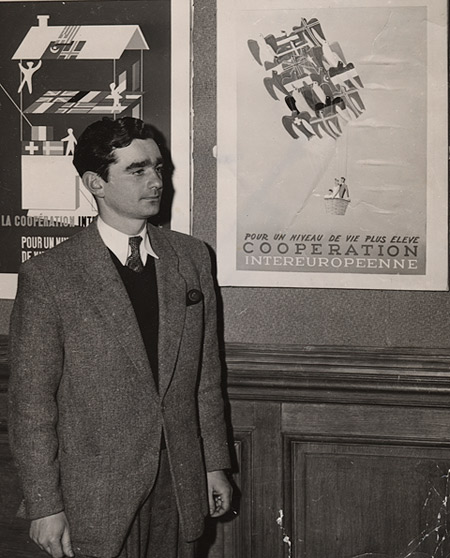

Uriel, Paris 1950

Uriel, Unesco contest, Paris 1950

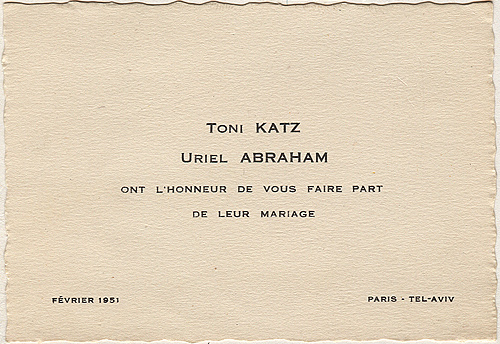

Uriel and Toni Wedding, "Paris - Tel Aviv", February 1951

Uriel and Toni Wedding, Paris, February 1951

- Interviews:

- Alex Neuhoff

- Alex Mallat

- Bitia Biesel

- Special Thanks:

- David Benaim, for the photo of the Benaim house, rue de l'Oise, Casablanca.

- Barbara Pollak, daughter of the photographer Paul Pollack, for sharing stories of our fathers in Casablanca during the war.

- Santiago Sanchez, for identifying his father on the Bou Arfa photo, sharing an uncropped copy of that photo, and sharing the story of his father.

- I am deeply indebted to:

- Eliane Ortega Bernabeu, for helping to uncover the a piece of my father's life in Bou Arfa in Fernando's Zambrana's journal.

- Jose Luis Morro Casas, for finding a mention of my father in Fernando Zambrana's journal regarding his sojourn in Bou Arfa.

- Maricruz Zambrana Jirash, Fernando Zambrana's granddaughter, for sharing her family's copy of the Bou Arfa photograph. (2025)

- Bibliography:

- Destination Casablanca: Exile, Espionage, and the Battle for North Africa in World War II. PublicAffairs, 2017.

- Years of Glory: Nelly Benatar and the Pursuit of Justice in Wartime North Africa. Stanford, CA; Stanford University Press, 2021.

- Les Camps de Vichy - Maghreb - Sahara, 1939-1944. Les Editions du Lys, 2005.

- Among The Righteous. PublicAffairs, 2006.