Moritz Abraham

Alternate names: Moshe, Moise

Name variations: Maurizio, Mauricio, Maurissio, Morisyo, Moritz, Maurice

Moritz Abraham, my grand-father, was born in Bulgaria, moved to Constantinople in his mid-twenties, later to Germany in his forties, then finally to Paris in his early fifties. Orphaned at the age of ten, he was a self-made man who made, then lost, a fortune.

Date of birth

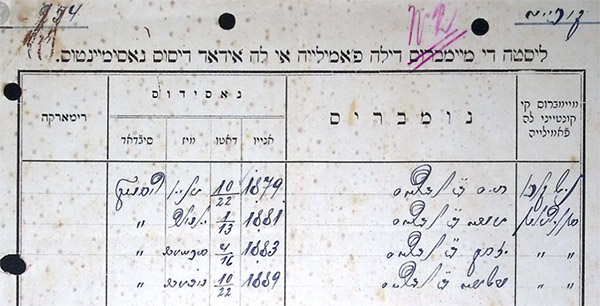

Moritz (Moshe) Abraham, the second child of Mamo Abraham and Lea Jacob, was born on January 13, 1881, in Ruschuk, Bulgaria. His given name at birth was Moshe; He went by Moritz in Constantinople, although he was also occasionally referred to as Maurice, which became his name after his immigration to France in the early 1930s.

List of Abraham family births drawn by the Sepharadic Congregation of Ruschuk in Ladino, 1901.

Moritz's is the second entry, under his birth name Moshe.

Source: Jabotinsky Archives

Although documents from the Sephardic Congregation of Ruschuk record his date of birth as January 13, 1901, Moritz and his family used at least six other dates over the years, including on passports, ID cards, and other legal documents.

The most credible birthdate for Moritz is January 13, 1881, since it appears in the 1901 records of the Sephardic Congregation of Ruschuk and in a 1932 German transcript.

Surprisingly, however, Moritz most often used January 21, 1883, as his birthdate, on his passports and French ID card. Not only is the day incorrect, but the year is also off by two years. This date is not credible, as his brother Isak was born later that same year—less than nine months afterwards.

- The 1929 business registry of the Spanish Consulate in Constantinople lists his birthdate as January 1, 1883.

- In the 1930s, in Düsseldorf, he used March 23, 1881.

- In July 1929, was registered as a member of the "Comunita Israelitica Straniera di Constantinople", and his date of birth was recorded as January 23, 1883. In 1942, during the German occupation of Paris, his identification card listed the same date .

- His son Uriel used March 23, 1882, on legal documents—getting the day, month, and year wrong.

- Finally, in the 1950s, his widow Ronya used only "March 1881" in a few legal documents, as if she didn't know the exact date.

Why did he use so many different birthdates, despite having an official birth certificate in his possession? Was he deliberately trying to obscure his age? Was he simply confused? And does this suggest he never celebrated his birthday—since even his own son got the date wrong?

At the time of his birth, Bulgaria used the Julian calendar—it would adopt the Gregorian calendar in 1916. January 13, 1881 (Julian) corresponds to January 25, 1881 (Gregorian). (Confusingly, according to stevemorse.org, January 13, 1881 (Julian) corresponds to January 25, 1882 (Gregorian). The reason being that, when regions switched from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar, the start of the year also changed, typically from March 25 to January 1. As a result, dates between January 1 and March 25 had their years adjusted retroactively. To avoid ambiguity, such dates were often double-dated, e.g., 1881/1882.)

Although the dating schemes seem confusing today, converting dates after the adoption of the new calendar must have been a very common at the time, so this doesn't seem to be the reason why so many variations exist for Moritz's date of birth, all of them seemingly incorrect.

Childhood

Little is known about Moritz’s parents, except that his father, Mamo, was a merchant in Ruschuk and that the family belonged to the Sephardic community.

Moritz lost his mother to tuberculosis when he was eight or nine years old, and his father when he was only ten.

After his parents's death, Moritz and two of his brothers—Haim and Isak—were raised by their maternal grandparents, Salomon (Mony) Jacob and Lea. Another brother, Mony, was raised by an aunt.

A group portrait taken in Ruschuk when he was fifteen is the earliest known photograph of Moritz.

Haim, Moritz, Isak, and Mony Abraham. Ruschuk, 1896.

Moritz Abraham, age 15, Ruschuk, 1896.

The clothes worn by Moritz and his brothers suggest a well-to-do, middle-class, Westernized background.

Very little is known about Moritz's early years in Ruschuk. However, we can assume that his life was similar to that of his older brother Haim, for whom there more information is available, and with whom he appears to have been close.

It is likely that, like his sibling, he first attended the elementary school run by the Alliance Israélite Universelle, where he would have learned French in addition to arithmetic, geography, history, science, a little Hebrew, and basic religious instruction.

He may have then attended the Ruschuk Gymnasium and, finally, completed his education at the Kronstadt Evangelical Realschule in Brașov. The curriculum there included mathematics, geometry, science, chemistry, and several languages: German, French, Romanian, and Hungarian. The foreign languages would later prove instrumental in his professional career.

Although no records survive to confirm that he followed this path, it is clear that he was influenced by the German culture. Like his brother Haim—who, for a time, went by "Heinrich"—Moritz, who was born "Moshe", adopted the Germanic name "Moritz".

Nothing is known about his life between 1896 and 1906.

A pair of tickets for the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris, preserved among family papers, suggests that he may have traveled to Paris at the age of 19 to attended the World's Fair.

Exposition Universelle, Paris,1900

Constantinople

In 1906, Moritz and his brother Haim left Ruschuk and moved to Constantinople.

Their arrival in the capital is mentioned—albeit with an incorrect date—in David Rimon's "HaMaccabi Be'Artzot HaBalkan" (The Maccabi in Balkan States):

"A few weeks after the Young Turk Revolution [July 1908], the brothers Haim Abraham and Moritz Abraham, members of Maccabi Ruschuk in Bulgaria, came to Constantinople. The brothers immediately went to work and devoted much of their time and energy to the development of the association."

In Constantinople, Moritz owned a succesful business with his oldest brother, Haim, fittingly called "Abraham Frères". They were brokers who sourced a variety of small manufactured products from Germany and neighboring countries, including razor blades, iron padlocks, shoe polish, and paper envelopes.

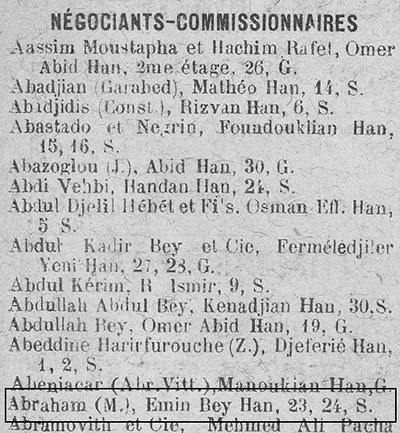

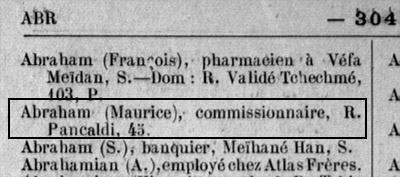

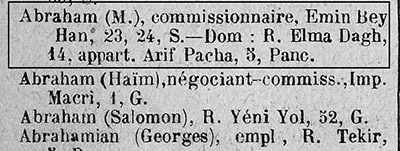

Moritz was variously described as "Négociant-Commissionnaire", "Commissionnaire" (in the French language "Annuaire Oriental"), "Merchant", "Négociant" (in the 1921 and 1922 Annuaire Oriental), or "Wholesale Merchant".

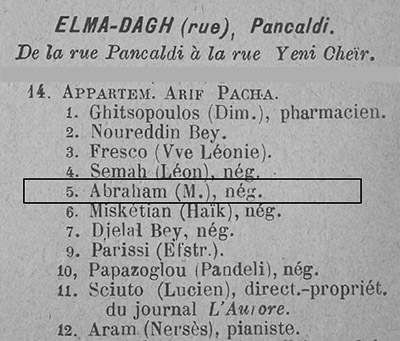

Annuaire Oriental 1921, p. 790

Maccabi in Constantinople

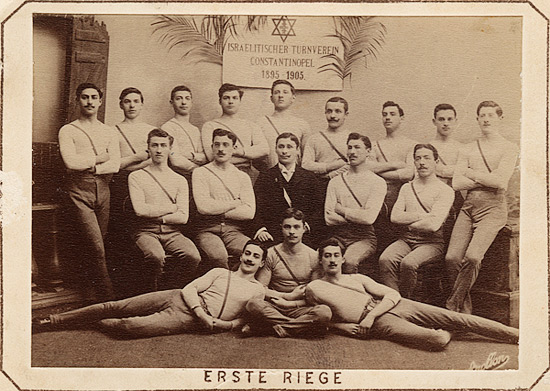

Moritz had been involved with the Ruschuk Maccabi Sports Club, as noted by David Rimon. In the family collection is this postcard, celebrating the 10th anniversary of the "Israelitischer Turnverein Konstantinopel". It's not clear what Moritz's connection with this event was, however, since belonged to Maccabi in Bulgaria, he may have participated in some fashion to the anniversary in Constantinople.

Card: Tenth Anniversary of the Israelitischer Turnverein Konstantinopel

The "Israelitischer Turnverein Konstantinopel" (Israelite Gymnastic Association of Constantinople) was founded in 1895 in Constantinople by Jews of German and Austrian extraction who had been rejected from participating in other social sport clubs. It would eventually evolve into the Maccabi Sports Club.

After his arrival with his brother Haim in Constantinople, his participation in the club is better documented. David Rimon, in "HaMaccabi Be'Artzot HaBalkan" (The Maccabi in Balkan states) states:

"[...] the brothers Haim Abraham and Maurice Abraham, members of Maccabi Ruschuk in Bulgaria, came to Constantinople. The brothers started working immediately upon their arrival and contributed a lot of their time and energy to the development of the [Maccabi] association."

[...] "Under the influence of a few Zionists who were in Constantinople at that time, the Jews launched an internal propaganda for nationalism and Zionism. Among these Zionist influencers were Dr. David Marcus, rabbi of the Ashkenazi community, and Dr. Victor Jacobson, a representative of the Zionist General Council in Constantinople and director of the Anglo-Levantine Bank. [...] A few months after the [July 1908 Young Turk] Revolution, Ze'ev Jabotinsky came to Constantinople. The influence of these Zionist leaders led by Jabotinsky, as well as the two Maccabis who came from Bulgaria [Haim and Moritz Abraham], caused a complete change in the character of the "Israeli Gymnastics Association", which in September 1908 already enacted a "national" [read "Zionist"] constitution."

Leadership of Maccabi, presumably in the courtyard of the Goldschmidt school in Pera, the main location of the Jewish Gymnastics Club in Constantinople. 1908.

Front row, lying on the left is Moritz Abraham; middle row, center is his brother Haim Abraham; back row center, sitting on pommel horse is Moritz Abramovitz, chairman of the association.

(Collection of the author)

This postcard, mailed from Munich on July 24, 1908, is addressed to "Herr Abraham, Isr. Turnverein, Constantinople". The date confirms that Moritz was already a member of the Jewish sports club prior to the Young Turk Revolution. Notably, the revolution reached its climax on the same day—July 24—when Sultan Abdul Hamid II capitulated and reinstated the Ottoman constitution.

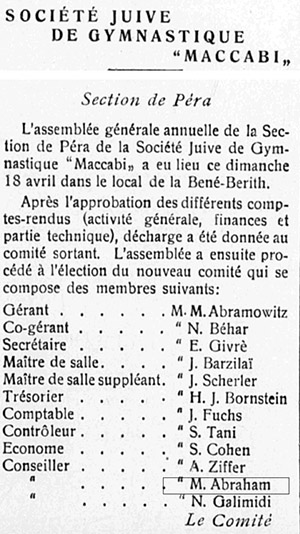

In the April 23, 1915, issue of l'Aurore, a pro-Zionist Jewish weekly published in Constantinople, a brief notice about the annual Maccabi assembly mentions "M. Abraham"—presumably Moritz Abraham.

M. Abraham is listed as one of three advisors, although his specific responsibilities are not clearly defined.

Jewish Gymnastic Association - Maccabi

Pera branch

The annual general assembly of the Pera branch of the Jewish Gymnastic Association Maccabi was held on Sunday April 18 in the premises of B'nai B'rith. [...] The assembly then proceeded to the election of the new commitee, which is made up of the following members:

Manager: M. M.Abramowitz

[...]

Advisor: A. Ziffer

" : M. Abraham

The last known reference to Moritz's involvement with the Maccabi association dates to the early 1920s, prior to the organization's dissolution by the Turkish government in 1923.

David Rimon, p106: "In the last years of the existence of the Maccabi, it was headed by Moritz Avraham."

However, no corroborating evidence has been found so far. Since a Moritz Avramovitch had previously led the group, it is possible that Rimon confused the two names.

Zionist Activism

Moritz was active in various Zionist groups in Constantinople from at least 1908 until the family's move to Germany in 1922–1923.

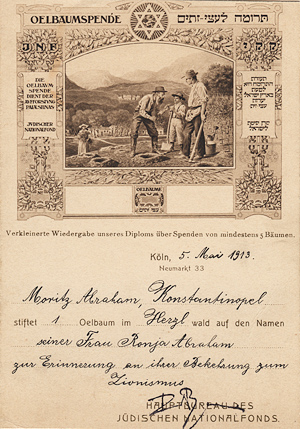

On the first anniversary of his marriage, Moritz purchased an olive tree in the Herzl forest in Jerusalem "for his wife, to commemorate her conversion to Zionism."

Tree certificate from the JNF, May 1913

This does not necessarily mean that Moritz considered immigrating to Palestine. According to "Jews, Turks, Ottomans", by Avigdor Levy:

"[...] little evidence to suggest that Turkish Zionists were very concerned by the emigration to Palestine". [...] Turkish Zionism tended to be more cultural than political. It was a search for a "national" identity at a time when other religious communities in the empire were asserting their own national identities."

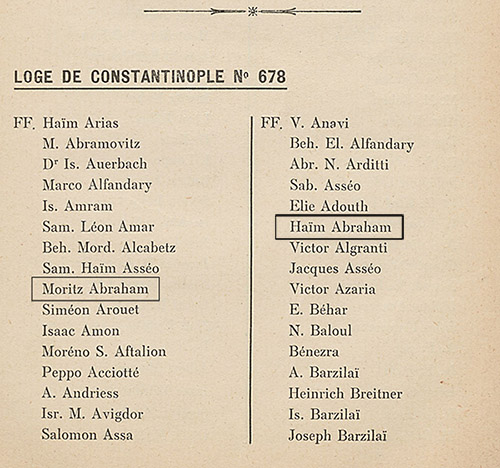

B'nai B'rith

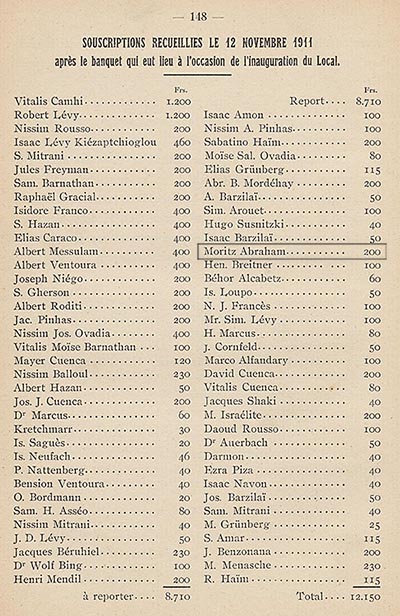

In 1911, a local lodge of the International B'nai B'rith order was established in Istanbul. Moritz and his brother Haim joined the lodge, along with many prominent members of the community. B'nai B'rith would go on to become one of the most active proto-Zionist organizations in Constantinople.

Donations for the opening of the B'nai B'rith premises, November 1911.

Source: archives.saltresearch.org, via Cenker Sarıkaya.

Alongside Moritz's name, the list features familiar Constantinople Zionist activists, including Nissim Russo, Joseph Niego, Dr. Marcus, Josef Barzilaï, Dr. Auerbach, and Moritz's cousin, Mayer Cuenca (Meir Coenca).

Aron Rodrigue, in The Alliance and the Emergence of Zionism in Turkey writes:

Grouping some of the leading members of the Jewish bourgeoisie, whether Sephardic or Ashkenazic, the lodges were philanthropic organizations designed to coordinate the charity and mutual help activities within these cities. They became particularly active in helping the needy among Turkish Jews during the Balkan wars of 1912-1913 and during World War 1. They soon became influenced by the activities of the many Zionists who joined the organization and who were successful in using it as yet another base of agitation against the Chief Rabbi Nahum.

[...] When the forced closure of many foreign institutions of secondary institutions upon Turkey's entrance into World War I threatened to leave many Jewish students without schools, the Constantinople lodge created a Jewish lycée in 1915, the first such Jewish institution in Turkey.

The lodges of the B'nai B'rith [...] went from strength to strength in Turkey in the years following World War I. By the early 1920s, they held all communal affairs in their hands. [...] the B'nai B'rith lodges were centers of extraordinary activism and enterprise in local communal affairs. Between 1908 and the early 1920s, the Alliance network had been dethroned from its position at the center of communal dynamism among Turkish Jewry by the class that it itself had brought into being.

Along with Haim and Moritz Abraham, the list includes Dr. Israel Auerbach, M. Abramovitz and J. Barzilaï from Maccabi. The following pages also include more familiar names: Meyer Coenca, Dr. Caleb, Dr. Wellich, Dr. D. Markus, Joseph Niego, Nissim Russo.

Fédération Sioniste d'Orient

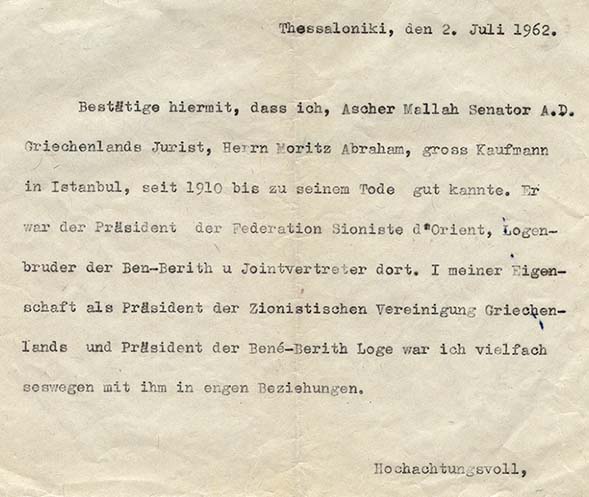

According to a 1962 testimonial by his brother-in-law Asher Mallah, Moritz served as President of the "Fédération Sioniste d'Orient" in Constantinople.

Letter from Asher Mallah mentioning Moritz's activities with the Fédération Sioniste d'Orient, B'nai B'rith, and the Joint.

Thessaloniki, July 2, 1962.

I hereby confirm that I, Ascher Mallah, Lawyer and Senator of Greece, knew Mr. Moritz Abraham, a wholesale merchant in Istanbul, very well from 1910 until his death.

He served as President of the Fédération Sioniste d'Orient, was a lodge brother of B'nai B'rith and Joint representative there.

In my capacity as President of the Greek Zionist Association and President of the B'nai B'rith Lodge, I maintained close contact with him on numerous occasions.

The "Fédération Sioniste d'Orient" (הסתדרות ציונית של המזרח) was established in 1919 and recruited around 4,000 members in Istanbul before ceasing its activities around 1922 or 1923. Following the proclamation of the Turkish Republic in 1923, all Zionist activities were prohibited, forcing Zionism to go underground. During its active years, the FSO published La Nation, a French-language periodical.

As an association with a limited regional scope ("the Orient") that was active for only a few years, the Fédération Sioniste d'Orient appears to have left very few traces, and little documentation seems to have survived. The only evidence of the FSO’s activities seems to be contained in issues of its official publication, La Nation, which I have not yet been able to access.

When I first translated this document, I hesitated to take it at face value, as I had never heard of my grandfather’s involvement in Zionist activities. Not only was this never mentioned at home, but I also couldn’t find any information about the FSO to corroborate it.

Since then, however, I have uncovered enough indications that my grandfather did indeed play a role—albeit presumably a relatively minor one—in the Zionist groups in Constantinople to take Ascher Mallah’s statement seriously.

The Joint

One interesting detail in this document is the mention of Moritz as a "Jointvertreter" ("Joint representative"), which I understand to mean a representative of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee—commonly known as the Joint or JDC—a Jewish relief organization.

The Joint was created in 1914 after Henry Morgenthau, the U.S. ambassador to Turkey, sent an appeal for urgent aid for the Jews of Palestine who, depending on outside support, had become destitute and risked starvation and death after the outbreak of the war. The Joint soon expanded its role, becoming the main provider of relief for Jewish populations suffering from the war.

The digitized archives of the JDC contain correspondance from 1915 to 1923 regarding relief efforts provided to the Jewish community in Constantinople. Between 1915 and 1918, the Joint appears to have worked with "prominent members of the Jewish community" as local intermediaries, including Chief Rabbi Nahum, Dr. Markus (Rabbi of the Ashkenazi Congregation), and the director and members of the Grand Lodge of B'nai B'rith. However, there are no mentions of a local branch or an official representative of the Joint during this period.

Starting in 1921, mentions of a local branch of the Joint begin to appear, and a letter from July 1921 identifies Dr. Tiomkin as the Joint's representative in Constantinople. If Moritz was indeed the Joint's representative there, I do not know when or for how long. So far, I have been unable to confirm Ascher Mallah's assertion.

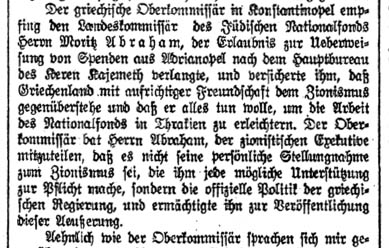

Another piece of evidence regarding Moritz's involvement with a Zionist organization is a short mention in a paragraph from the Wiener Morgenzeitung—a Jewish daily published in Vienna—dated July 27, 1922, in which Moritz is identified as the "National Commissioner of the Jewish National Fund."

"The Greek Chief Commissioner in Constantinople received the National Commissioner of the Jewish National Fund, Mr. Moritz Abraham, who requested permission to transfer donations from Adrianople to the main office of Keren Kayemet, and assured him that Greece stood with sincere friendship toward Zionism and that he would do everything to facilitate the work of the National Fund in Thrace. The Chief Commissioner asked Mr. Abraham to inform the Zionist Executive that it was not his personal stance on Zionism that made his assistance possible, but rather the official policy of the Greek government, and authorized him to publish this statement."

Another paragraph refers—though without naming him directly—to someone I believe may be Moritz:

The Sephardic community also has a Zionist majority in its "Conseil Communal," whose president is simultaneously the president of the Fédération Sioniste d'Orient and president of the National Commission of the Jewish National Fund for Turkey.

The article describes internal conflicts within the Federation but offers no specific details or names:

When the Federation Sioniste d'Orient was organized after the end of the war, it too had to accept a subsidy from the Zionist Executive in London, commensurate with the importance of this new foundation.

[...] bitter opposition arose against the Executive of the Federation Sioniste d'Orient within the ranks of the organization itself, which reproached it most vehemently for having accepted this subsidy.

And although the Federation currently receives its support from the Executive, the main theme of every opposition speech is still that two years ago it took money from London.

The article provides a very brief overview of the challenges Zionism faced in Turkey:

Before the war, Zionist work in Turkey was very difficult; during the war and before the Young Turk Revolution, it was impossible.

Champions of our idea, such as the current Vice President of the Jewish National Fund for Constantinople, Mr. Abramowicz, were imprisoned, and the general political uncertainty made Zionism appear to the Turks as high treason. As a result, all Zionist work proceeded haphazardly, almost underground, and even the few successful actions of this period owed their success to chance.

It also highlights a problem that affected Dr. Israel Aurbach, Dr. Markus, Moritz Abramovitz, and, presumably—though to a lesser extent—my grandfather:

The Zionist leaders are overwhelmed with work, and each one has three or four Zionist offices.

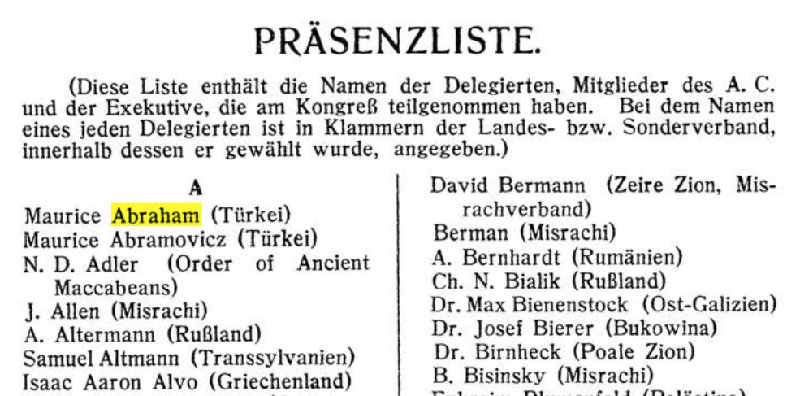

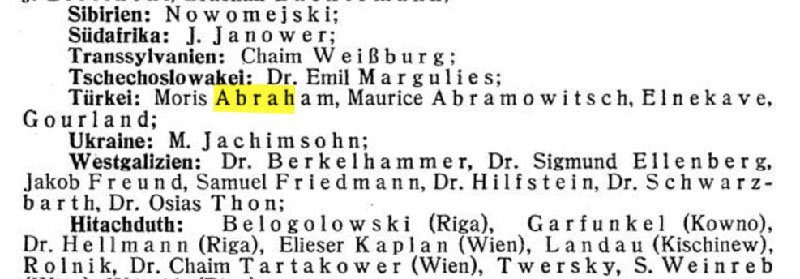

Zionist Congresses

The transcript of the Twelfth Zionist Congress, held in Carlsbad from September 1 to 14, 1921, lists Maurice Abraham as one of five delegates from Turkey. Among the other Turkish delegates are two familiar names: Maurice Abramovicz, chairman of Maccabi association, and Dr. Israel Caleb, a family friend. (Both are mentioned in Aaron Aaronsohn's diary in July 1915: "I go pick up Ronya [...] at the Pera Hotel to go to Abramovitch where Dr. Caleb will give me injections against cholera.". The other two delegates were David Elnékavé, editor of the Spanish Zionist newspaper “El Judio", and Aaron Gourland.

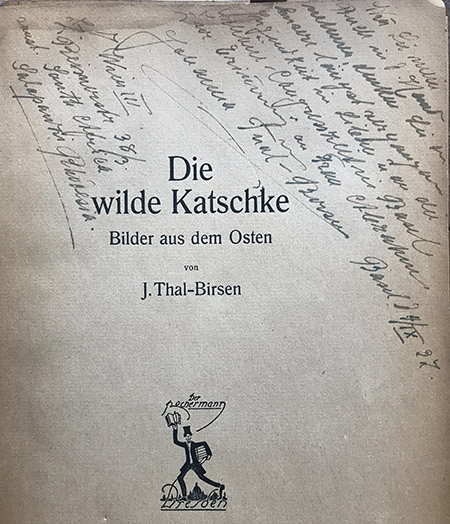

An inscription in a book by Johanna Thal-Birsen, Die wilde Katschke: Bilder aus dem Osten, addressed to my grandmother, offers some circumstantial—albeit possibly tenuous—evidence that Moritz may have attended the 15th Zionist Congress in Basel in 1927. However, the official list of delegates includes no representatives from Turkey, and his name does not appear anywhere on it. This suggests that if he did attend, it was not in any official capacity.

Inscribed first page of "Die wilde Katschke: Bilder aus dem Osten" by Johanna Thal-Birzen, dedicated on the occasion of the 15th Zionist Congress in Basel, 1927.

"If you hold my book in your hand, think of our long gone youth in Libau and to the pleasant Congress time in Basel.

In memory of Mrs. Abraham,

Johanna Thal-Birsen Basel 4 September 1927"

(Johanna Thal-Birsen was a writer and journalist from Libau, and a family friend.)

Marriage

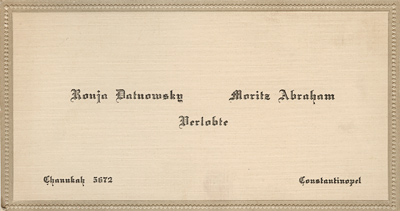

Moritz was introduced to his future wife Ronya Datnowsky, a young woman from Libau ten years his junior, through Israel Auerbach and his wife, Berta - who was Ronya’s older sister.

Ronya's mother had died in 1909. Shortly thereafter, Ronya and her younger sister Eva moved to Constantinople to stay with Berta. Berta's husband was a prominent member of the Jewish community, and through his social circle, Berta arranged for her sisters to find "suitable" husbands.

Ronya and Moritz became engaged in December of 1911.

Engagement announcement

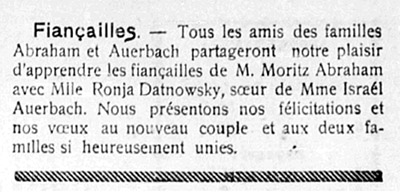

Their engagement was announced in the December 22 issue of Die Welt, the central publication of the Zionist movement.

The engagement was also mentioned in the December 22 issue of L'Aurore, the Jewish weekly published in Constantinople.

L'Aurore, Constantinople, December 22, 1911

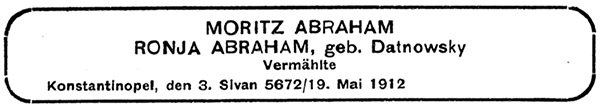

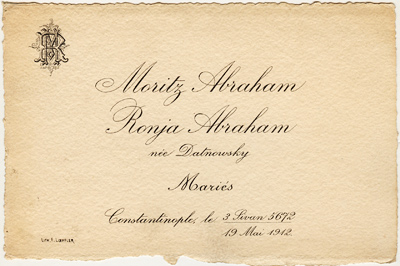

Moritz and Ronya Datnowsky were married five months later, on May 19, 1912, in Constantinople. Moritz was 31, and Ronya 21.

Ronya and Moritz, Constantinople, May 1912

Wedding announcement in French, 1912.

Their marriage was announced in the May 31, 1912, issue of Die Welt.

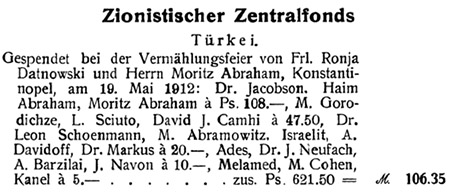

The May 31, 1912, issue of Die Welt, the official Zionist organ, published a list of donors to the Central Fund of the Zionist Organization in honor of Moritz's and Ronya's marriage. This list, containing the names of several prominent members of Zionist and Jewish organizations in Constantinople, provides valuable insights into their social circle:

- Dr. Victor Jacobson, representative of the Zionist General Council in Constantinople and director of the Anglo-Levantine Bank;

- Lucien Sciuto, editor of L'Aurore, the Zionist weekly of the capital. (He coincidentally lived in the same apartment building as the Abraham family);

- Abramovitz, head of the Maccabi sports association;

- Dr. Markus, Rabbi of the Ashkenazi community, and an active member of several Zionist groups.

- A. Barzilai, presumably Aaron Barzilai, member of the central Consistory, possibly related to Jacques Barzilai of of the Maccabi leadership;

Other names includeMelamed (possibly Meir Melamed, from Maccabi Bulgaria), David Camhi, Dr. Leon Schoenmann, A. Davidoff, Dr. Neufach, J. Navon, M. Cohen, Kanel, Ades, Israelit, and Gorodische, a name I remember from my chidlhood. (Mrs. Gorodische was a friend of my grandmother's from Constantinople, who met again in Germany in the 20s, then in Paris in the 30s);

Life in Constantinople

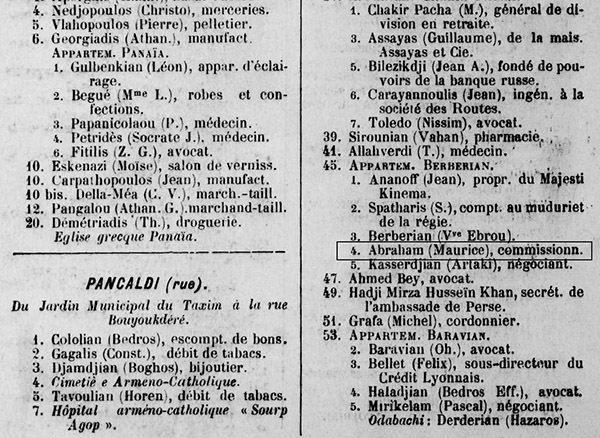

In 1913*, Moritz and Ronya lived at 45 Rue Pancaldi, in the Berberian Apartments, located in Pera (now Beyoğlu), a residential district of Istanbul. According to the 1914 issue of the Annuaire Oriental, their neighbors included lawyers, bank directors, business owners, physicians, and a retired army general. (* The 1914 issue of the Annuaire Oriental had to have been printed prior to January 1914.)

Annuaire Oriental, 1914

Annuaire Oriental, 1914

Surprisingly, Moritz was listed as "Maurice", a name I assumed he'd only started to use after moving to France in the 1930s. Since he used the German variation in other occasions, this suggests that he alternated between the two, depending on the context.

Sometime between the end of 1913 and 1915, Moritz and Ronya appear to have moved to a new location. In April 1915, Israel Datnowsky sent a postcard to a different address: "Sourp-Agop, Berberian Han 4".

From 1915 until at least 1921, their address was 14 rue Elma Dagh.

Annuaire Oriental, 1921

Trying to pinpoint the couple's exact address is complicated by the fact that multiple variations seem to have been used for the same location.

For example, the following variations seem to all point to the same address:

14 rue Elma Dagh, Appartement Arif Pacha, 5, Pancaldi

Sourp Agop, Arif Pacha Han, Appartement #5

Arif Pacha, Apartment #5, Elmadag 14 (Pancaldi)

According to this contemporary map, Appartements Arif Pacha and Appartements Sourp-Agop were two distinct buildings, both in the same street.

Appartements Arif Pacha and Appartements Sourp-Agop

Courtesy of Cenker Sarıkaya

This photo, showing the funeral procession of a German sailor, was taken from the apartment of Moritz and Ronya in 1913.

"Funeral for a German sailor"

View from Moritz and Ronya's apartment in Constantinople, 1913.

Comparing this photo with the map fragment above, it looks like it was probably taken from the Sourp-Agop location.

The 1913 date is plausible: In 1913, four German sailors from the battlecruiser SMS Goeben died while fighting a fire at the Ottoman army barracks in Constantinople. Their funeral was a major public event.

This date however would seem to contradict what I believe was their previous address (Berberian Apartments, 45 Rue Pancaldi), unless this was the same building but with a different name and address variation; Another possibility is that the year 1913 is wrong and there was another funeral for a German sailor at a later date.

Annuaire Oriental 1921

Lucien Sciuto, the owner of L'Aurore, the pro-Zionist weekly, and apparently part of Moritz's social circle (he would later attend his wedding) lived in the same building.

Children

On March 17, 1917, Moritz and Ronya's first child, Gedeon (Gisi), is born

Moritz and Gisi, Constantinople, 1917 or 1918

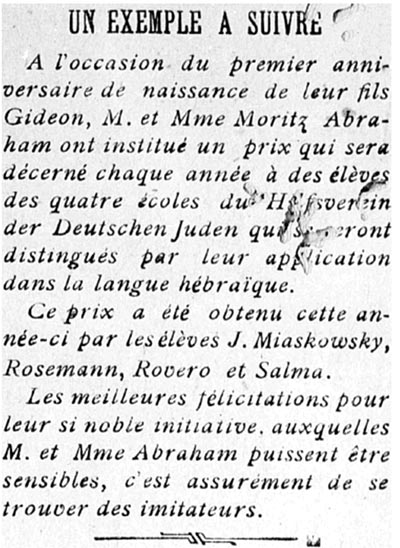

A year later, on March 22, 1918, L'Aurore, the pro-Zionist Jewish weekly, announces that Moritz and Ronya have established a prize to commemorate their son Gedeon’s first birthday. The prize is to be awarded annually to students from four schools affiliated with the Hilfverein der Deutschen Juden who demonstrate excellence in Hebrew. Four students are selected in the inaugural year, 1918.

L'Aurore, 22 March 1918

On October 26, 1918, their second son, Uriel (Uly), is born.

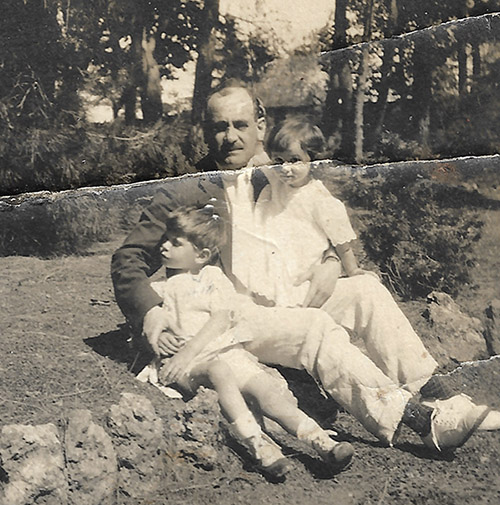

Moritz with Gisy and Uly, Constantinople, 1919.

Moritz with Gisy and Uly, Constantinople.

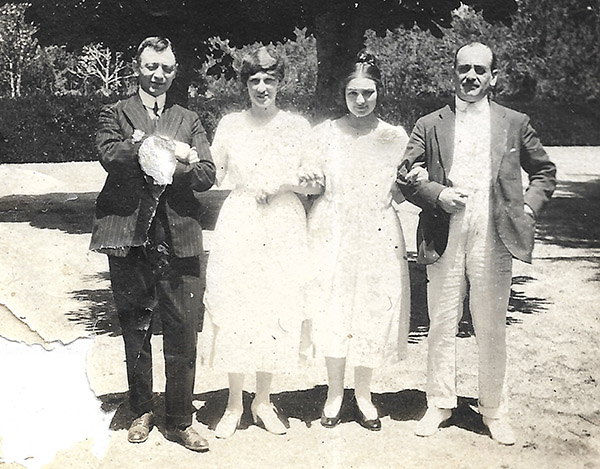

Dr. Caleb, Mlle Lowy, Mlle Wertheimer, and Moritz Abraham, Erenkeuy, 1921.

(Dr. Caleb, a member of the B'nai B'rith lodge, is mentioned in the January 1, 1915, issue of L'Aurore as a member of the committee for establishing the Jewish high school. He is also mentioned in Aron Aaronsohn's diary ["Dr. Caleb will give me injections against cholera."]. In 1922, he is described in The Hebrew Standard as a local representative of the Zionist Organization.

"Mlle Wertheimer" is possibly Elfrida (Mädi) Wertheimer, Mony Abraham's wife, or perhaps her sister, Alice.

Erenkeuy is a small village located about half an hour away from Constantinople.)

Nationality

Born in 1881 in Rustchuk, three years after Bulgaria gained autonomy in 1878, Moritz would have been a Bulgarian subject. (Although the Principality of Bulgaria was technically a vassal state of the Ottoman Empire, in practice, it had its own administration, and Ottoman rule was largely symbolic.)

As such, he was considered a foreign national in the Ottoman Empire, and may have been under the protection of the Bulgarian legation in Constantinople.

By the time Bulgaria achieved full independence in 1908, Moritz had already been living in Constantinople for two years. Presumably, he would have been registered as a Bulgarian citizen, although no documentation survives in the family archives to confirm this assumption.

In October 1912, the Balkan League, comprising Bulgaria, Serbia, Greece, and Montenegro, declared war on the Ottoman Empire. The Bulgarian army advanced as far as the outskirts of Constantinople, where its offensive was finally stopped.

It is impossible to know how Moritz experienced this conflict, or where his loyalties lay. Although he was 32 years old, he might still have been subject to military conscription. As a native of Bulgaria residing in the Ottoman capital, Moritz must have, at the very least, been viewed with suspicion by the Turkish authorities.

Further complicating matters, his wife Ronya had been a Russian citizen prior to their marriage. While Russia was not a belligerent in the war, it supported the Balkan League.

This may explain why Ronya, who had never worked until then, volunteered as a war nurse with the Ottoman Red Crescent.

Becoming Spanish

The birth certificate of his first son, Gisy, was issued by the "Community of Foreign Jews in Constantinople", confirming that Moritz did not hold Ottoman (Turkish) nationality.

The reasons and circumstances for his acquiring a new, somewhat artificial nationality - he had never even set foot in Spain - are not clear. This decision however would later prove extremely fortunate as it would provide him and his family some unusual consular protection during the German occupation of Paris during WWII.

I remember my mother telling me that after the First World War, people where he lived were able to chose their nationality. According to her, he had at first considered applying for the Austrian nationality, because it seemed more desirable to have an Austrian passport than a Turkish one.

However, again according to my mother, upon learning that as an Austrian national he would have to serve in the Emperor's army, he had concluded that he was not so eager to become an Austrian citizen after all, and decided to apply for a Spanish passport instead.

Note: my mother's explanation doesn't seem to make complete sense, at least as described above, as there would not be an Emperor to fight for after the end of WW1. It is possible that Moritz could have considered the Austrian nationality before WW1 - then the issue of becoming a soldier would have made sense. It's also possible that he may have considered the option after WW1, but judged that after the defeat and the disintegration of the Empire, the Austrian nationality was not so attractive after all.

According to my father, Western European powers, including Spain, wanted to claim as many citizens as possible in the Ottoman Empire - in order to increase their position in regards to the Capitulations which gave them influence and economic rights in Turkey.

Coming from a town were all the Jews were Sepharad and spoke Ladino, he was considered by Spain a descendant of Jews expelled from Spain in 1492, and thus could claim Spanish citizenship.

However, the Primo de Rivera law which granted Spanish nationality to descendants of Sephardic Jews was passed in 1924; Yet Moritz and his wife Ronya already held Spanish passports by 1922. It seems however that the Spanish Consulate in Constantinople had already been providing passports to Sephardic Jews in the region before the existence of the 1924 law.

According to "The Spanish Consulate in Istanbul and the Protection of the Sephardim (1804-1913)" by Pablo Martín Asuero, Sepharad Jews were already granted Spanish protection by the Consulate in Constantinople before the 1924 law. According to this document, a number of Jews had left the new Balkan states in 1912/1913 to settle in Istanbul, and some of them requested the protection of the Spanish consulate. Asuero mentions "... 70 records of Sephardic protection that date to 1913 [... containing] information on around 220 people [including] the names of the spouses and children."

It seems that the request for Spanish protection was generally granted to Jews of Spanish origin, especially if they had sufficient means - their protection then beeing deemed beneficial for Spain.

The following could certainly have been applied in Moritz's case:

"The applicant has a good background and a wealthy position which in his capacity as trader and trade representative can serve Spanish interests."

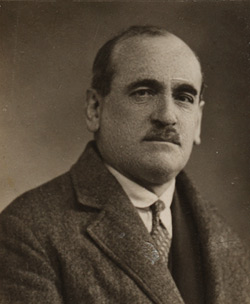

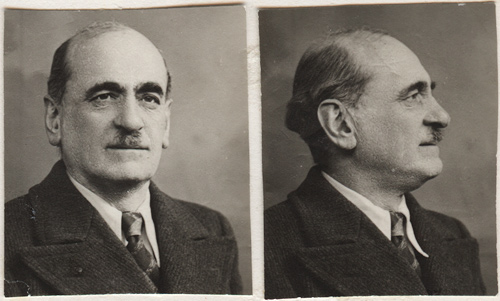

Moritz, ca. 1921

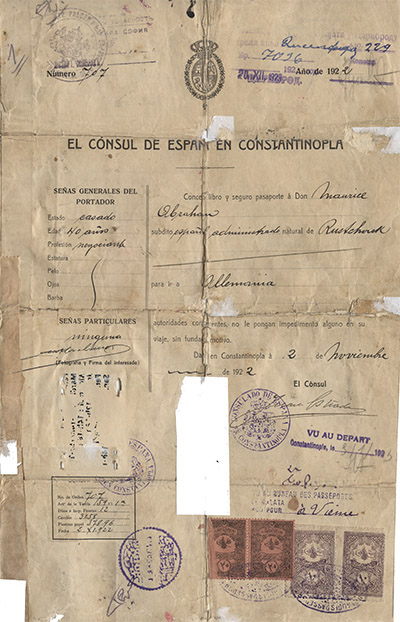

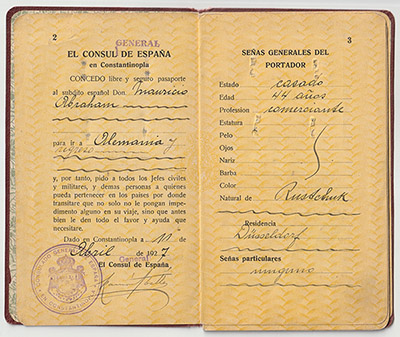

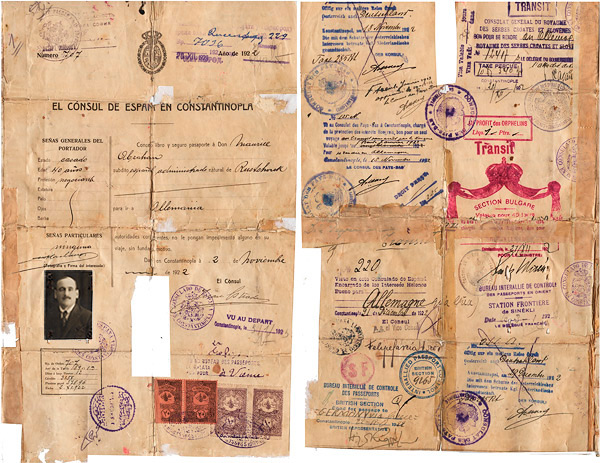

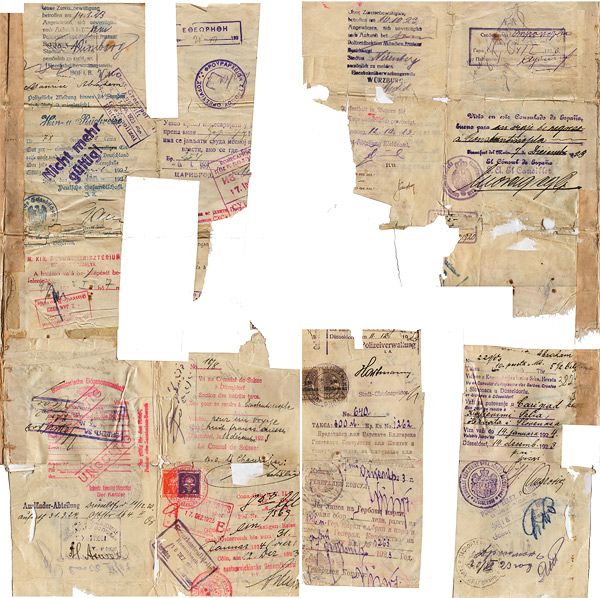

Moritz's Passport, 1922

This travel document was delivered by the Spanish consulate in Constantinople in November 1922. It consists of four pages covered with stamps, showing Moritz's travels to Germany between December 1922 and January 1923, with transit through Serbia, Greece, Hungary, Holland and more... A few more stamps are for travel to Vienna, Constantinople and Bulgaria in 1923.

I grant (?) a free and secure passport to Mr. Maurice Abraham,

Administered (i.e. "Protected"?) Spanish subject

Native of Ruschuk

for Germany

Relevant authorities, do not hinder his travel in any way, without a (valid?) reason.

Constantinople, November 2, 1922

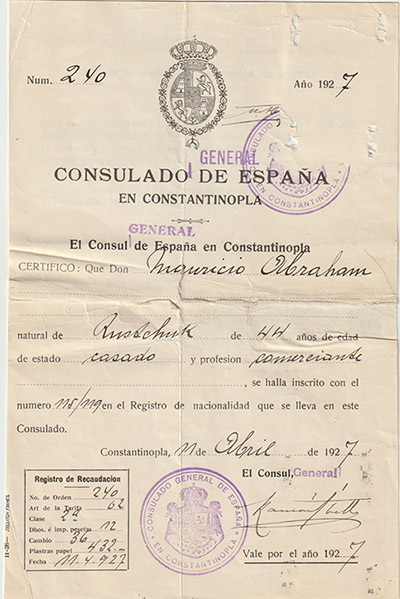

By 1927, Moritz was a Spanish citizen. He held a certificate of Spanish nationality from the Consulate in Constantinople, and a passport, both issued on April 11.

The Consul General of Spain in Constantinople

Certifies: That Mr. Mauricio Abraham,

a native of Rustchuk,

44 years old,

married,

and a merchant by profession,

is registered with number 115/119 in the Nationality Registry kept at this Consulate.

Constantinople, April 11, 1927

It is not known when Moritz and the family first acquired Spanish citizenship. While this passport dates from 1927, it is likely that he had already become a Spanish national a few years earlier, since his wife Ronya and their two children had been issued a certificate of Spanish nationality in October 1923.

This passport shows that Moritz left Istanbul in early July 1927 and came to the family home in Düsseldorf, where he remained for a few months. His two-day train journey - presumably aboard the Orient Express - took him from Turkey to Bulgaria, Serbia (Subotica), Hungary (Kelebia), Austria (Bruckneudorf), and finally Germany. The Orient Express stopped in Köln, where he would have taken another train to Düsseldorf, an hour away.

The last pages of the passport contain two exit visas from Germany, one from November 1927, the other April 1928. It is not clear if he stayed in Düsseldorf for four months or nine months. (My father recalled that Moritz would be away for about six months out of the year, but making several trips.)

A small quirk: despite this being an official document, his name appears both as "Mauricio" and as "Moritz".

Düsseldorf

According to my mother, Ronja didn't want to live in Turkey and argued that since Moritz's business operated between Germany and Turkey, the family might as well live in Germany, which corresponded more to her lifestyle expectations.

In 1922, Moritz purchased an empty lot in Düsseldorf on LindenmannStrasse, across from St Pauluskirche.

LindenmanStrasse, Düsseldorf. The empty lot where the house was built.

Düsseldorf is close to Solingen, a region known for its cutlery/metal blade industry; the choice of Düsseldorf may have been caused - at least in part - by its proximity to several suppliers of Abraham Frères (Germania-Werk, Kamphausen & Plümacher, etc.)

It seems that Ronya went to Germany with Uriel and Gisy first, while Moritz stayed in Constantinople, taking care of business. While the house was under construction, Ronya, the children, and their nurse stayed in a pension in Düsseldorf. After the house was finished, the family moved in and, in December 1922, Moritz came to Düsseldorf.

According to a December 8, 1922, letter from Elfriede (Mädi) Abraham (wife of Mony) to Ronya, Moritz's departure had been delayed because:

"Something happened that nobody could have predicted. [...]"

"Moritz had to postpone his trip. He already had his passport with all his visas [...]"

"Now he's not going to leave until the situation with Haim is taken care of. He is hoping it will be resolved in about 12 days."

The acrimonious dispute between Haim and Moritz resulted in their partnership Abraham Frères being dissolved. From now on, Moritz would continue to operate a similar business on his own from an office in the same location.

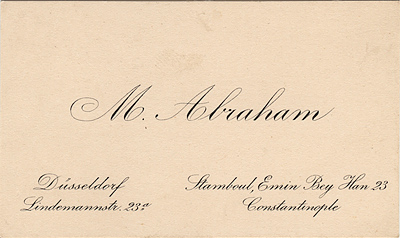

Moritz Abraham's business card: Düsseldorf & Constantinople - 1920s.

Moritz's primary residence was now in Düsseldorf but he still retained an office in Constantinople: Stamboul, Emin Bey Han 23, although it was now reduced to a single office (#23).

23 LindenmanStrasse, Düsseldorf. The house is the first one on the corner.

The house in Düsseldorf

The house in Düsseldorf

The living room, 1925

The Dining Room and "Winter Garden", LindenmanStrasse. 1924

Photo Marcel Fresco.

In 1923 or 1924, Moritz sold an apartment in the Shahkulu district in Constantinople. The address doesn't correspond to where the family used to live, so it's not clear what this apartment was, whether an investment property or an apartment belonging to a relative. (Note: need scan?)

1927

The only photo of Ronya and Moritz together after leaving Constantinople.

Ronya and Moritz with friends, Bachrach on the Rhine, 1927

Moritz and Ronya's lifestyle was somewhat extravagant - Uriel said that at one point they had up to five employees in the house: a gardener, a butler, a chauffeur, a nurse and a cook. This was most apparently Ronya's idea.

This lifestyle however didn't last. According to my mother, one evening Moritz came home and announced to the family: "It's over - it's all gone." Whether this story is real or apocryphal is not known; What is certain, however, is that something did happen with Moritz's fortune. All his money was apparently invested in the stock market, and he lost it all - seemingly overnight.

According to the story I was told, this loss of money prompted the family to leave Düsseldorf and move to Paris.

A few things aren't clear though. I was told that this coincided with the 1929 market crash; however, there is a certificate "de fin de séjour" (end of stay) dated December 24, 1928, indicating that the family was planning to leave Düsseldorf and go to Paris as early as the end of 1928.

This either means then that this reversal of fortune had happened before the crash of October 1929 - the result of bad investments perhaps (my mother said that the fortune was "all on paper"). Otherwise, it would mean that they had planned to go to Paris before losing their fortune.

The other questions are: why leave? and why Paris? The destination was most likely not driven by business imperatives, as Moritz doesn't seem to have ever dealt in French manufactured products. As for the changing political climate in Germany, I never heard that the rise of Nazism had been the reason for the family's departure. While it could have been a factor, it would have required an incredible ability to foresee the future, a quality Moritz and Ronya didn't display a decade later when the Germans invaded Paris.

Confusing the timeline, there are a few photos of Ronya and the children in Düsseldorf dated 1930. The earliest photos of the family in Paris date from 1930, so it's not clear why they had this "end of sojourn" certificate dated December 1928.

Registry Entry - January 1929:

| Registry Book 1928-1930 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family Name | Given Name | Name of Parents | Date of Birth | Place of Birth | Profession | Registry Date |

| Abram | Morisyo | Mamo and Lea | 23 January 1883 | Ruse (Ruschuk) | Merchant, J. Emin b-h. | 29 January 1929 |

In July 1929, Moritz still retained the same business address - Emin Bey Han, No 23.

Although the Abraham Frères partnership had ceased to exist since the early 20s, Moritz continued to be involved in a similar import business.

His nephew, Alex Mallat, recalled that, in Düsseldorf, Moritz had owned a "large steel company named MORA"; However this is something I'd never heard at home nor have I found any documents that would confirm this.

Alex's recollection may actually have come from Morris Halle's memoir:

"Moritz Abraham was in the steel business in Germany. At one time he produced safety razor blades which my father tried to sell in Latvia. The attempt was unsuccessful, but we had thousands of sample blades about the house. In fact, we first began to buy blades several years after we came to America. Until that time, the MORA blades that my father had at home made such purchases unnecessary."

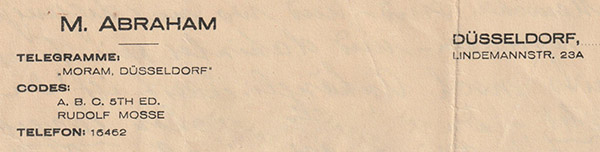

A 1929 letterhead points to the likely source of this name: his telegram address was "MORAM Düsseldorf". Thus it appears that he now did business under the "Mora" or "Moram" moniker; It is however likely that he ever owned a "large steel company"; instead, he most likely continued to be a commission agent or maybe a distributor.

Letterhead, 1929.

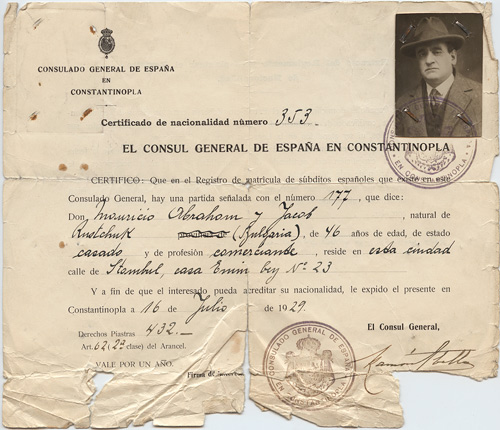

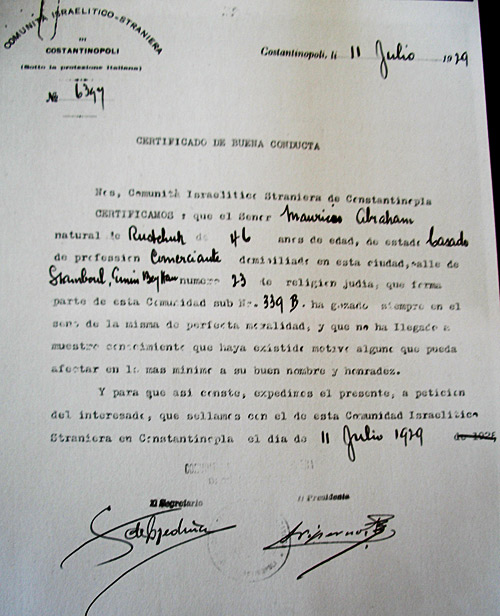

On July 11, 1929, Moritz and his family were registered with the Comunita Israelitico Straniera di Constantinople—the Foreign Jewish Community of Constantinople.

The same day, he was also issued a "Certificate of Good Conduct".

Certificate of Good Conduct, July 1929.

Courtesy of Pablo Martín Asuero

Constantinople, July 11, 1929

Foreign Israelite Community of Constantinople.

Certificate of good conductWe, the Foreign Israelite Community of Constantinople, certify that Mr. Mauricio Abraham, originally from Ruschuk, 46 years old, married, merchant, residing in this city, Stamboul, Emin Bey Han, number 23, of Jewish religion, is part of this community [registered] under number 339.

He has always enjoyed the same perfect moral standard and to our knowledge there is no motive that could affect in the most minimal way his name and honor.

Consequently, we expedite this petition for the interested party and we affix our seal of the Community of Foreign Jews of Constantinople.

11 july 1929.

The Foreign Jewish Community of Constantinople was the umbrella communal body for all foreign Jews in the capital-primarily Jews who were citizens of European countries, especially those under the protection of European consulates. In the absence of a separate institution serving the Spanish Jewish community in Istanbul, this community provided legal, religious, and social support in a way the Ottoman rabbinate could not.

Moritz—whether still a Spanish-protected Sephardi, or a Spanish citizen—was not an Ottoman subject but a foreign national in the eyes of both the Ottoman authorities and the Jewish communal framework.

Five days later, on July 16, Moritz received a certificate of nationality from the Spanish Consulate. It is possible that he had to register with the Foreign Jewish Community in order to obtain the letter of recommendation, which may have been required to secure his certificate of nationality.

Moritz, late 1920s

Paris

The family moved several times after arriving in Paris, athough they always remained within the 16th arrondissement. Their first address was 12 bis, rue des Marronniers. In 1930, they lived at 117 boulevard Exelmans, then moved to 67 rue Erlanger. This last residence was apparently a sublet, as a card from Gisy that year was addressed to "Abraham, chez Santon". (The timeline for these different addresses is confusing. For example, the family's residence was listed as 12 bis, rue des Marronniers in the 1936 census.)

The family's lifestyle was clearly a far cry from what they had enjoyed in Düsseldorf. The apartments were likely small, as Gisy and Uriel initially attended Lycée Lakanal, a boarding school on the outskirts of Paris. (There may have been other reasons for their enrollment there; the school had a significant number of foreign students.)

By 1933, the family had moved again, this time to 122 boulevard Murat, still within the 16th arrondissement.

Moritz, Paris, 30s

In France, Moritz continued to run a similar business, now under the name Société SOCOM. No information survives regarding the type of merchandise he dealt in. In the 1936 census, his occupation was listed as négociant (trader or merchant), under the name Socom, located in the 17th arrondissement.

Visas in his passport are the only evidence that he continued to travel across Europe, presumably to meet with manufacturers.

Passport, 1934

Every few months, Moritz traveled for business. Over a six-month period, his trips included the following destinations:

July 1934: Austria, Hungary, Yugoslavia, Switzerland, Serbia

October 1934: Austria

December 1934: Romania, Austria, Switzerland, Hungary

The family's diminished lifestyle in Paris clearly indicates that Moritz's business was only a shadow of what Abraham Frères had once been.

In September 1939, the family moved one last time, 35 rue de Lübeck, again in the 16th arrondissement.

1940-1943

In May 1940, Germany invaded France. On June 3, 1940, the Germans bombed Paris, and half of its population joined a mass exodus, fleeing the German advance. Among them was Moritz's son, Uriel, who managed to reach the south of France by bicycle, then boarded a ship to Casablanca, where he would spend most of the war. Moritz and Ronya decided to remain in Paris.

Why they decided to stay is a mystery. Moritz had been involved with Zionist activism during his Constantinople days, his brother Haim had moved to Haifa in 1932, while Ronya's sisters had done the same - Liska Mallah in 1934 and Bertha Auerbach in 1937. Ronya herself had taken a month-long trip to Palestine in 1938. Did Moritz and Ronya ever consider immigrating? Did they underestimate the dangers that lay ahead for Jews under Nazi rule? Or did Moritz not have the will to leave, maybe due to ill-health?

Moritz, 1939

How Moritz experienced the German occupation of Paris is a mystery. No oral history and no documents, whether letters or official papers, remain to give any insights on what happened to Moritz between 1940 and 1942.

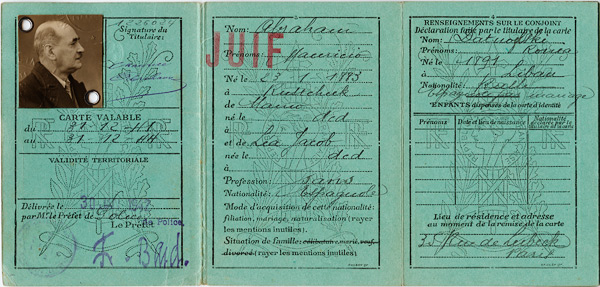

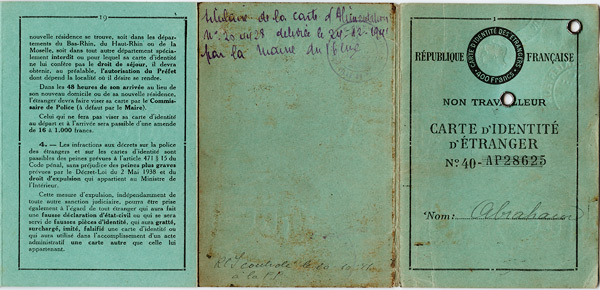

On October 31, 1940, the census in the Seine department was completed. The data collected, containing the names of 151,000 Jews in the Paris area, will later be used to create the "Fichier des Juifs". It is presumed that Moritz and Ronya complied, as Moritz's foreign identity card, issued in January 1942, bears the red "Jew" stamp.

On November 29, 1941, the French government created the Union Générale des Israélites de France (UGIF, or General Union of French Jews), an organization that all Jews living in France were required to join. Although the UGIF archives for the Paris region do not appear to have survived, it must be assumed that Moritz and Ronya were registered with UGIF.

While the Germans expropriated Jewish businesses - (i.e. "Aryanisation") - they agreed in May 1941 to allow Spain to administer the assets of Spanish Jews. Moritz's company, SOCOM - most likely a one-man operation - was placed under the oversight of a Spanish "Aryan" administrator appointed by the Spanish Consulate, and supervised by the Spanish Chamber of Commerce in Paris. (A 1947 letter to his wife mentions a "Mr. Costa", the administrator for the company, presumably the same person who had beeing appointed during the German occupation.)

Beginning on October 1, 1941, by order of the Police Prefecture, all Jews, both French and foreign, had to report to the authorities. This reporting was to be periodic, so that the authorities would be aware of their situation and activities at all times.

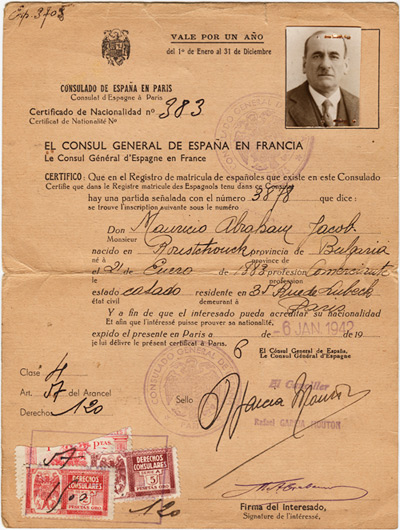

Certificate of Nationality No. 383

The Consul General of Spain in France

Certifies that the Spanish Register of Citizens held at this Consulate contains the following entry under number 3878:

Mr. Mauricio Abraham Jacob

Born in Rustchouk, province of Bulgaria

on January 21, 1883

Occupation: Merchant

Marital Status: Married

Residing at 35 rue de Lubeck, Paris

And so that the person concerned may prove his nationality, I hereby issue this certificate in Paris,

on January 6, 1942

Chancellor

Rafael GARCIA MOUTON

Although his Spanish certificate listed Moritz as a merchant, his foreigner card issued by the French Police on January 30, 1942, stated that he was not working - most likely not by choice but because as a Jew he was not allowed to run a business anymore.

Moritz and Ronya most likely did not wear the yellow star because Spaniards weren't required to. His identity card however bore the red "Jew" stamp.

Moritz's foreign card. Paris, January 30, 1942.

French Republic

Foreign Identity Card

Non-Worker

Card valid from 31.12.41 to 31.12.44

Issued on January 30, 1942

By the Prefet de Police, François Bard*

JEW

Abraham Mauricio

Born 23.1.1883 in Ruscthuk

Son of Mammo, deceased,

and Léa Jacob, deceased.

Profession: none

Nationality: Spanish

Spouse: Ronia Datnowski

Born 1891 in Libau

Nationality: Russian, Spaniard by marriage

35 rue de Lubeck, Paris

Holder of food card no. 204428 issued on 24.12.1941 by the city hall of the 16th arrondissement.

RCS Controlled on 20.10.41 at the P.[refecture de] P.[olice]

*François Bard will oversee the "Green Ticket Roundup" in Paris in May 1941 with SS Theodor Dannecker, head of the section responsible for the Jewish question at the Parisian Gestapo.

On June 2, 1942, the French government issued the Law of June 2, 1942, known as the "Second Jewish Statute". This law expanded the Vichy regime's legal definition of who was considered to belong to the "Jewish race" and further restricted the rights of Jews in France. It included a detailed list of professions from which Jews were now barred, including Moritz's trade: broker and commission agent (courtier, commissionnaire).

Bernardo Rolland, Consul General of Spain in Paris, reported:

"[...] I would like to point out [...] the provisions of the penultimate paragraph regarding foreign Jews who are required to report to the prefecture for the replacement of their identity cards.

It is assumed that their merchant cards will be withdrawn and they will be provided with private (non-travailleur) cards, thus automatically prohibiting them from engaging in any activity."

Under Spanish protection

On July 16 and 17, 1942, the French Police, under Nazi orders, rounded up over 13 000 foreign Jews in Paris, (Rafle du Vel' d'Hiv.) Holding Spanish passports, Moritz and Ronya were not targeted.

As a child, I had been told that my grandparents had been protected during the German occupation thanks to the official policy of Franco's Spain, which didn't have racial laws and would't let Germans extend their policies to Spanish citizens.

In reality, they were protected not by the Spanish government, but thanks to the actions of Bernardo Rolland, Consul General of Spain in Paris from 1939 to 1943.

Bernardo Rolland resisted German orders and directives from his own government, instead providing letters of protection for Jews with Spanish nationality, the great majority of whom actually came from the Balkans, like Moritz Abraham.

From: VISAS for freedom (pdf)

In October 1940, the Spanish Consul in Paris, Bernardo Rolland, informed the Minister of Foreign Affairs about the new anti-Jewish measures that also affected the 2,000 Sephardic Jews with Spanish nationality residing in the French capital. The Statut des Juifs envisaged a gradual stepping up of discriminatory measures, viz., registration, expropriation and, ultimately, detention and deportation.

By means of "letters of protection" Rolland succeeded in having the Spanish Sephardim excluded from most of the anti-Jewish laws. "There being no Act referring to a Statute on Jews in Spain", wrote Rolland to the Minister on 24th October, "no Foreign State or Authority may classify Spaniards and accept these measures [...]".

However, the Madrid government had no wish to associate itself with the Consul's stance, and on 9th November the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Serrano Suñer, wrote to his Ambassador in Paris, José Felix Lequerica, leaving no doubt as to Spain's position:

"While it is certainly true that in Spain no race law exists, the Spanish Government cannot raise objections, even in the case of its subjects of Jewish origin, to prevent them from being subjected to general measures, its sole duty being to consider itself informed of such measures and, if the worst comes to the worst, place no obstacles in the way of their enforcement by maintaining a passive attitude".In the latter part of 1941, Rolland again wrote to his superiors in Madrid inquiring as to the course of conduct to be followed in the event of the possible confiscation of assets of Spanish subjects of Jewish persuasion. Here, Madrid's reply was more active; however, it did not entail the task of protecting the persecuted parties but rather that of responding to Germany wherever Spanish sovereignty might be encroached upon. In this case, Spain's -not disinterested- position marginally benefited Spanish Jews (nationals and protected persons alike), because Consul Rolland managed to protect their assets and prevent their expropriation, by appointing non-Jewish Spanish administrators.

In August 1941, after a massive raid in Paris in which 7,000 people were apprehended, Rolland interceded to secure the freeing of 14 Spanish Jews who had been sent to the Drancy transit camp. Rolland did not apply the Ministry's restrictive orders regarding establishment of Spanish nationality to the letter, and in some cases also extended consular protection to persons that had the nationality but for a variety of reasons had not been entered on the Citizens' Register created by the 1924 Decree. At all times, the Spanish Sephardic Jews' desperate requests for protection or repatriation were forwarded by Rolland to Madrid.

Bernardo Rolland wrote in 1942:

"Spanish law does not discriminate among [Spanish] citizens because of their religion, and for that reason it regards Jews who *originally* came from Spain as Spaniards, despite their Jewish religion. For this reason, I would be grateful if the French authorities and the occupying power would be good enough not to impose upon them those laws that apply to Jews"

Source: Note 49 CDJC, 32/180A, reply from Rolland, July 23,1942, to letter from the Commissariat General aux Questions Juives, July 22, 1942

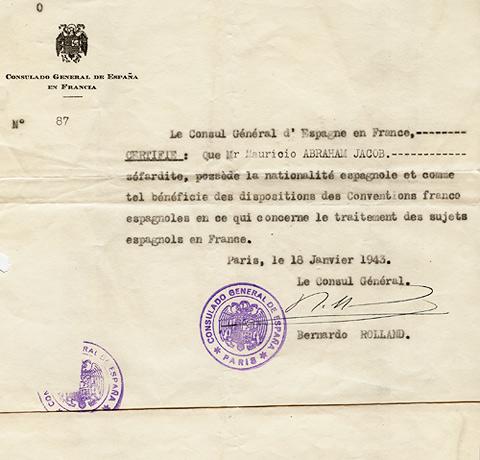

Bernoardo Rolland provided letters to Moritz and Ronya stating that they were Spanish nationals, thus providing them temporary protection.

The Spanish Consulate in France certifies that Mr Mauricio ABRAHAM JACOB, a Sepharad, is a Spanish national, and as such benefits from the provisions of the French-Spanish covenents concerning the treatment of Spanish subjects in France.

Paris, January 18, 1943.

The General Consul

Bernardo Rolland

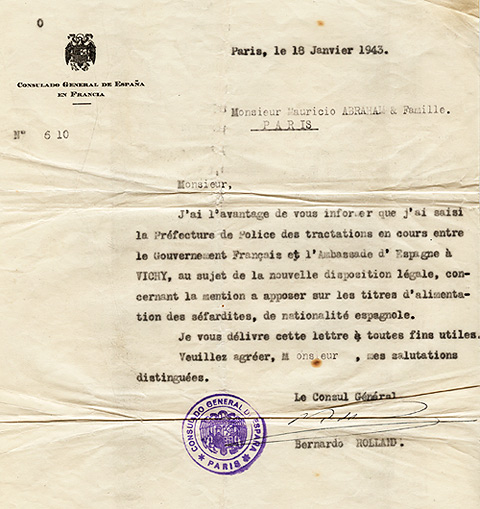

Paris, January 18, 1943.

Mr Mauricio ABRAHAM and family.

I am pleased to inform you that I have contacted the Police Department regarding the ongoing negociations between the French Goverment and the Spanish Embassy in Vichy concerning the new legal regulations regarding the reference(*) to include on food tickets of Sepharads with the Spanish nationality.

I send you this letter for all intents and purposes.

Best salutations.

The General Consul,

Bernardo Rolland*: meaning stamping the word "Jew".

Moritz's business, Société SOCOM, located 17 rue Lasson, was listed by the Spanish Consulate as being registered with the Spanish Chamber of Commerce in Paris.

On January 31, 1943, Moritz passed away at home.

It was said that he had been sick and bed-ridden for a while, although the nature of his ailment was never described, the only explanation being that, due to the "circumstances" - being a Jew in Paris during the German occupation - "he wasn't well and hadn't received the treatment he needed".

Which doesn't explain much.

This lack of transparency on the actual cause of his death is particularly strange, as I was given more specific information about the death of his brother Mony (uremia). Meanwhile, it seems that Ronya misrepresented the suicide of her brother Isrolke, having told her sister and the family he had died of typhus.

By this time, Moritz must have been quite depressed. Transplanted in Paris, far away from where he had grown, he probably had few, if any, friends. He was not working, and not having been able to regain his footing after losing his fortune in the 1920s, he had been living in very different circumstances from what he had known in his younger years. Probably as a result of this reversal of fortune, Ronya appears to have shown him little love or support. The loss of his first son Gisy had affected him badly. Two of his brothers, Mony and Isak, were dead, and he had had a falling out with his older brother and former partner Haim.

Although Spanish Jews had been shielded from deportations, Moritz had to feel increasingly anxious from his status as a foreign Jew in occupied Paris. By 1943 however, it appeared that that protection might come to an end, which would have been devastating.

Although it is impossible to know for sure, all of these facts have led me to conclude that there is a very strong possibility that an ailing, demoralized Moritz actually ended to his life.

After burying him, Ronya would flee Paris and find a temporary refuge in Spain.

- Special Thanks:

- Mehmet Sadettin Fidan, for providing records related to Moritz Abraham's professional activity. (www.hanmektuplari.com (dead link)

- Pablo Martín Asuero, for copies of the 1929 "Certificate of Good Conduct" and 1928-1930 Spanish Consulate Registry Book

- Bernd Philipsen, for uncovering a wealth of publications with references to the Abraham family, including the Wiener Morgenzeitung, 27 July 1922 article mentioning Moritz's role as "National Commissar of the Jewish National Fund".

- Alain De Tolédo, Director of Muestros Dezaparesidos, for providing much information about the action of Bernardo Rolland and answering my questions about the situation of Spanish Jews in Paris during the German occupation. (2025)

- Cenker Sarıkaya, for his invaluable help and for uncovering artifacts related to the Abraham brothers in Istanbul, including the B'nai B'rith's

Bulletin de la Grande Loge de district XI . (2025).

- Sources and References:

- HaMaccabi Be'Artzot HaBalkan (The Maccabi in Balkan states), by David Rimon

- The Spanish Consulate in Istanbul and the Protection of the Sephardim (1804-1913), by Pablo Martín Asuero

- Morris in Latvia 1923 - 1940, by Morris Halle (private publishing)

- De l'Egée et de la Baltique à la Seine, by Alex Mallat (unpublished memoir)

- El Cónsul General Bernardo Rolland de Miota, y los Sefardíes de París (1939-1943), Matilde Morcillo. Ed: Riopiedras Ediciones, 2016.

- The Alliance and the Emergence of Zionism in Turkey, by Aron Rodrigue, retrieved from www.doku-archiv.com

- Jabotinsky Archives

- sammlungen.ub.uni-frankfurt.de (Stenographisches Protokoll Der Verhandlungendes XII Zionisten Kongresses In Karlsbad vom 1 bis 14 September 1921. JÜDISCHER VERLAG BERLIN)

- archives.saltresearch.org (Annuaire Oriental, 1921)

- es.wikipedia.org (Bernardo Rolland)

- www.raoulwallenberg.net (Bernardo Rolland)

- VISAS for freedom (pdf)

- fr.wikipedia.org (Lois sur le statut des Juifs du régime de Vichy)