Libau

Current name: Liepaja - Libau was the German name. Libawa was pre-Russian Revolution.

Libau (Liepaja) is a Baltic port city on the northern end of Lake Liepaja, in the Courland (Kurland) region.

The key Baltic ports of Libau and Windau (now Ventspils) are ice-free throughout the winter, a fact that was critical to Courland's commercial success.

During the second half of the 19th century important developments took place in Russia's foreign trade, its export being channelled to a great extent through the Baltic sea ports of Riga, Libau and Windau.

Two important railway lines were laid for the export of Russian grain through Libau and Windau. These two ports had the advantage over Riga of being open for shipping all the year round, whereas the big port of Riga was closed during the winter months because of massive ice. To store the grain at the exit ports, huge silos were built with modern facilities for speedy loading into vessels. Libau had a further economic asset, namely a naval port where part of the Russian Baltic fleet was stationed.

These economic changes had a great impact on the port cities, which prospered and grew fast.

Languages

German was the official language in Latvia until the 1880's, while Russian was the language of the government and schools between that time and the First World War. Lettish on the other hand was young both as an official language and as a language of civilization in general. Consequently, German and Russian enjoyed much more prestige than they would have as languages of rather inconsiderable minority groups within the country.

Most Jews spoke three or four languages, typically German, Russian, Yiddish, and maybe a little Lettish.

Jews in Latvia

The independent Republic of Latvia was proclaimed on November 18, 1918, and Jews, for the first time, were granted civil rights to their full extent.

Jewish life in Courland

Jewish settlement began in Kurland in the 16th century. The first-comers originated from East Prussia. The greater part of Jewish immigration into Kurland, however, came across the southem border from Lithuania.

Note: Internet searches return significantly more results for "Datnowsky + Lithuania" than "Datnowsky + Latvia", suggesting that the Datnowsky may have originally come from Lithuania.

Kurland was incorporated into the Russian Empire in 1795. Its Jewish population at that time amounted to less than 5000 souls. While only 20% lived in towns, while 80% found a livelihood in the countryside, on the large estates of the German Barons, as petty artisans, innkeepers, land tenants and peddlars. In 1850, fifty-five years later, the Jewish population in Kurland had grown to 22,000; and by the end of the century, in 1897, it reached the impressive number of 51,000.

Although banned from permantent residence in Kurland - since it was not part of the Pale of Settlement - Jews nonetheless found ways to evade these restrictions and settled in this region of Latvia.

By the end of the 19th century, the German language was prevailing, but also literature in Yiddish and Hebrew. German (and not Yiddish) was the spoken language of the Jewish community and continued until World War II.

Kurland was not part of the Pale of Settlement (the part of Russia where Jews were permitted to live), and only those who were born there had the right of residence. In spite of restrictions, however, the influx of Jews from other parts of Russia, and in the first place from Lithuania, was considerable throughout the 19th century.

The Emancipation and the ensuing urge for contemporary education in neighbouring Germany infuenced the Jews in Kurland who were perceptive to Western culture, their language being German (Kurisches Deutsch), even if they also spoke Yiddish.

The German cultural influence on the Jewish population there was paramount. The historian Wunderbar remarks in his book, which appeared in 1853: "As to the Jews of Kurland's education,even the poor do their utmost to give their children a fair education, and among the adults there are practically none who do not command the German language."

The Revolution of 1905

Despite the fact that Kurland scarcely had an organized labour force among its Jewish population, Jewish youth took an active part in the rising against the Russian Government in 1905.

They paid a high price for their participation, when the reaction set in and the Revolution was smashed with an iron fist. To liquidate the revolting Latvian peasants who had rebelled against their German barons landlords, the Russian Government sent a punitive task force of Cossack and dragoon detachments to Kurland.

Latvian peasants in hundreds were executed on the spot, while Jewish revolutionaries - real or suspect - were not spared.

Jewish life in Libau

Jews were not permitted to settle in Libau until the 18th century.

The Jewish population peaked at almost 10,000 in 1920 (about 19% of the total population). By 1935, the Jewish population had declined to about 7,400. In August, 1940, the city was annexed to the Soviet Union. The Germans occupied the town on June 29, 1941. During the first month of occupation, at least 1,000 Jewish men were taken to the Baltic seashore and shot to death. Almost 3,000 Jews (including women and children) were killed between December 15-17, 1941. In June, 1942, a ghetto was established. This ghetto was liquidated in October, 1943, with the remaining Jews sent to the Kaiserwald camp, near Riga. When the Red Army entered Liepaja on May 9, 1945, there were no more than 30 Jews remaining.

Litvaks

Libau was part of Courland and is now part of Latvia. Courlanders (Kurlanders) were considered Litvaks, at least culturally.

One definition of Litvak is a Lithuanian Jew, however Jews from outside Lithuania may also be considered Litvaks. Litvaks are Jews from the Pale of settlement, especially from the Vilna and Minsk Gubernias, who settled in Congress Poland at the end of the 19th century. Many were under the influence of Russian culture and language.

A number of mundane characteristics contrast Litvaks from other Ashkenazi Jews, such as Yiddish dialect differences, culinary tastes and varying methods of food preparation. Religious differences include reciting Friday night Kiddush sitting, or praying while standing rock still, only moving one's lips. In a more general sense Litvaks are characterised as being "more rational, dogmatic and authoritarian" than other branches of Ashkenazi Jewry.

Jews in the Baltic States were followers of the Vilna Gaon - they were called Mitnagdim, (later known as the orthodox), meaning the opposers (of the new emotional, anti-rational Hassidim). In 1784 the Gaon ruled that the Hassidim were heretical, and the animosity between the groups was intense. It was during this period that the term Litvak came into being to differentiate the Lithuanian Jews from the remaining, predominately Hassidic Jewish world of Eastern Europe.

Haskalah, the movement of enlightenment which came to Lithuania from the West, moving through Germany, took hold especially in Vilna (Vilnius) and Minsk.

Emancipated Jews looked upon themselves as a mediator between the old rigid orthodoxy and the radical assimilationists.

The Haskalah movement opened up Lithuanian Jewry to the other new movements, Zionism and Jewish Socialism. The Jewish Bundists played a major part in the Russian Revolution.

The Pale of Settlement

After the third partition of Poland in December 23, 1791, the decree limiting Jewish habitation to White Russia (Byelorus) and the Ukraine was extended to include the newly acquired territories along the Baltic Sea.

Thus began the Pale of Settlement that stretched from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea. Of the areas then inhabited by Lithuanian Jewry , ethnic Lithuania and Byelorussia became an integral part of Russia. The southern part, around Grodno and Suwalk became part of the Duchy of Warshaw (Poland). At the time of partition about a quarter of all Jews in eastern Europe were Litvak.

Excerpted from Morris Halle's memoir

Jews on the whole did not consider the local Latvian society and culture as sufficiently attractive to attempt to assimilate into it. Jews rarely spoke Latvian at home. In the Halle family and in the families of most of our friends the major language was German.

When Jews assimilated, they assimilated to either German or Russian culure. They would not dream of becoming Latvianized.

During the half-century preceding World War II, life for Jews in Latvia was far from easy, but it was perfectly supportable.

Hasidism failed to become dominant in Lithuania and in Latvia, although there were some followers. This had direct consequences on the character of the Jews living in these areas, who were called Mitnaggedim. Mitnaggedim were - according to Morris Halle's description - rational, unemotional, hard working and demanding people.

Libau Fragments, by Ze'ev Wolf Joffe

http://www.jewishgen.org/Yizkor/libau/lib001.html

When I was born it was officially "Libawa". For Kurland Jews, only its German name counted, - Libau. In the competition between the German and the Russian influences, the "real" Kurlandic Jewry leaned toward the Germans. For Germans were considered the bearers of Western, liberal civilization.

It took a German, Interior Minister Plehwe, to further the Russification of the Baltic. Plehwe sacrificed his phobia of Jews to the more pressing task of Russification. Hence, he denied recognition of the [German] Numerus Clausus [limiting the entry of Jews to a percentage, equivalent to their proportion in the population] for entry into Russian gymnasia [classical secondary schools, running through 14th grade] and universities. The share of Jews in the population of Libau admitted to gymnasia and universities under the reign of the Czar was dependent upon the election of state officials.

In the reign of the Czar, the privileged Jews of Libau lived in an atmosphere of liberal tolerance. My oldest brother, a first-year student in the school of commerce, associated with his fellow students, - Russians, Germans, Latvians and Jews, in cooperative harmony. The humanistic spirit was realized and one tried to align oneself with it.

When the Germans occupied Libau during the First World War, they experienced it not as foreign, but as any old East-Prussian small town. The German-speaking Jews willingly supported the cultural ambitions of the German garrison.

The Jews, however, already had a more impressive promise of eventual autonomy, the Balfour Declaration. Before this historical occurrence, Zionism was indeed just a dialectical Platonic diversion for the Kurland's privileged Jews. It became more acute when the well-established Jewish bourgeoisie collapsed during the war. Its classless offshoots not only spread outside of the former working class but also from the educated class. They formed gangs of youths, which showed signs of organized criminality, mixed with military trappings.

In the beginning, the newly established state of Latvia was good to the Jewish population. In the euphoria over their newly acquired independence, the Latvians presented a democratic and liberal image. Now the Jewish community could begin their auto-emancipation. Profane Yiddish and Hebrew schools and Yeshivas were established which interpreted biblical Hebrew in Yiddish. This was supported by the state. However, the main part of Jewish pupils still attended private German grammar schools. The idea was that this would secure the future of the children in the western world.

As time went on, the Latvian influence became more predominant. This was simply a method of removing the competition of the minorities, above all that of the Jews, and to urbanize the surplus of Latvian peasantry. The future of Jewish youth looked bleak. These trends were not limited to the Baltic region but soon engulfed all of Europe. The fascist doctrine that spread like an epidemic destroyed the west European options of the Jewish youth of Latvia one by one. The only remaining option was to emigrate overseas. Overseas also included Palestine.

- Sources and References:

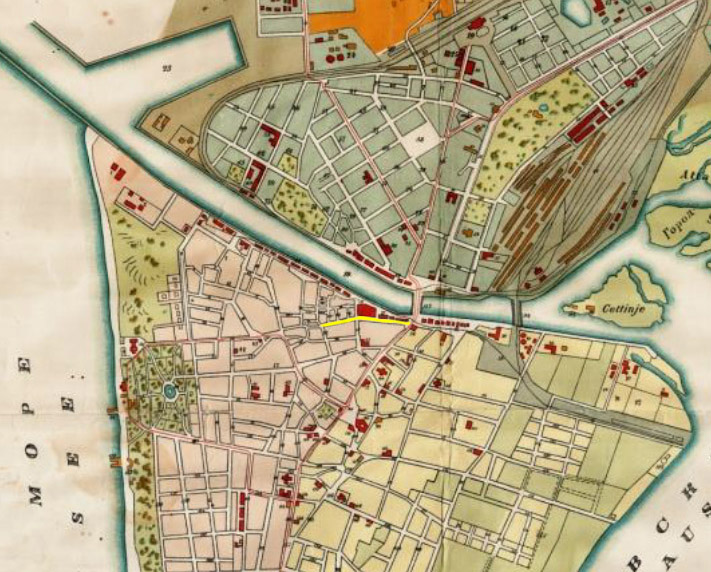

- www.geo.lu.lv (1900 map of Liepaja. Territory Planning Concepts and Urban Development in the Renewed Latvia Republic (1990-2015), Silvija OZOLA, 2015.)

- liepajajewishheritage.lv

- www.jewishgen.org (Libau Yizkor book)