Moritz Abraham

Alternate names: Moshe, Moise

Name variations: Maurizio, Mauricio, Maurissio, Morisyo, Moritz, Maurice

Moritz Abraham, my grand-father, was born in Bulgaria, moved to Constantinople in his mid-twenties, then to Germany in his forties, then finally to Paris in his early fifties. Orphaned at the age of ten, he was a self-made man who made, then lost, a fortune.

Date of birth

Moritz (Moshe) Abraham, the second child of Mamo Abraham and Lea Jacob, was born on January 13, 1881(*) (January 1st according to the Julian calendar in use at the time of his birth) in Ruschuk, Bulgaria.

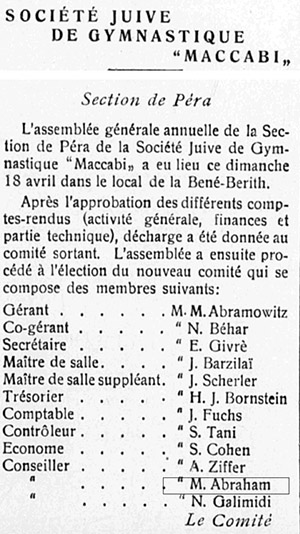

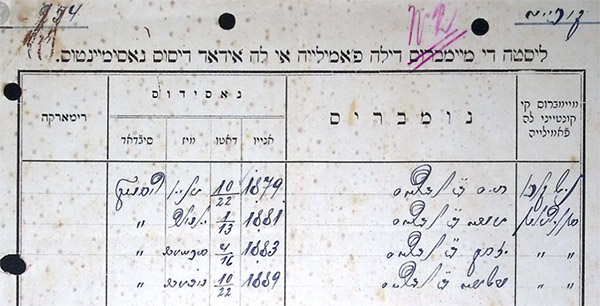

List of Abraham family births drawn by the Sepharadic Congregation of Ruschuk in Ladino, 1901.

Moritz is the second entry, under his birth name Moshe.

Source: Jabotinsky Archives

Despite the existence of document from the Sepharadic Congregation of Ruschuk with his birthdate dating from 1901, Moritz and his family used no less than six other dates over the years, including on passports, Identification cards and other legal documents.

- The most credible birthdate for Moritz is 13 January 1881. This is the date that appears on the 1901 list from the Sepharadic Congregation of Ruschuk, and on the 1932 German transcript.

- Surprisingly, though, he most often used January 21, 1883, on his passports for example, or his French ID card. Not only is the day wrong, the year is off by two years. This date is not credible since his brother Isak was born in 1883, less than 9 months later.

- The In 1929 business registry of the Spanish Consulate in Constantinople had his birdthdate as January 1, 1883. The day matches the original Julian date, but the year is again off by two years.

- Later in the 1930s in Düsseldorf, he used March 23, 1881.

- In 1942, during the German occupation in Paris, his identification card had the incorrect date January 23, 1883.

- His son Uriel used March 23, 1882 for legal documents, getting the day, month and year wrong.

- Finally, his widow, Ronya, simply used "March 1881" in a couple of legal documents in the fifties, as if she didn't know the exact date.

Why did he use so many variations since he had in his possession an official birth certificate? Did he have reasons to obfuscate his age? Was he confused? Does this mean he never celebrated his birthday, as even his own son got the date wrong?

Technical note: When calendars switched from Gregorian to Julian, the beginning of the year also changed, typically from March 25th to January 1st. Because of this, any date between January 1st and March 25th had to have its year adjusted retroactively, so that January 1, 1881 in the Gregorian calendar would become Januay 13, 1882 in the Julian calendar. To remove any ambiguity, such dates were typically double-dated, in this case 1881/1882. The Ruschuk document, written in 1901 (and thus before the calendar change), includes two dates for the days (1/13) but only a single year, presumably because double-dating the years would be used only after the adoption of the new calendar. If that was the case, then the correct date would be January 13, 1882. See wikipedia.org.

Adding to the confusion: I wonder if the use of "March 23" could be explained as being an approximation of the former date for the Gregorian new year, March 25th.

Although the dating schemes seem very convoluted today, converting dates after the change of calendar must have been a very common occurence at the time when Moritz was still a young man, so it still isn't clear why so many variations exist.

Childhood

Nothing is known about Moritz's parents, save that Mamo, his father was a merchant in Ruschuk, and that the family belonged to the Sepharad community.

Moritz lost his mother to tuberculosis when he was eight or nine, then his father when he was only ten years old.

After his parents died, Moritz and two of his brothers - Haim, and Isak were raised by his maternal grandparents, Salomon (Mony) Jacob and Lea. Another brother, Mony, was raised by an aunt.

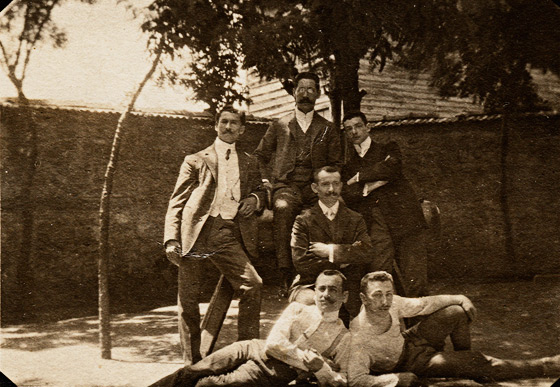

A group portrait taken while he was fifteen in Ruschuk is the only document from his early life.

Haim, Moritz, Isak and Mony Abraham. Ruschuk, 1896.

Moritz Abraham, age 15, Ruschuk, 1896.

The clothes Moritz and his brothers are wearing suggests a well-to-do, middle-class westernized background.

Very little is known about Moritz's early life in Ruschuk, however we can assume that his life was similar to the life of his older brother Haim, for whom there is more information, and with whom he seemed to have been close.

I assume that, just like his brother Haim, he first attend the elementary school run by l'Alliance Israelite Universelle, where he would have learned French. He then most likely attended the Ruschuk Gymnasium. There he would have learned German, among the many other required subjects.

Probably following the lead of his older brother Haim, he belonged to the Ruschuk Maccabi - the Jewish gymnastic association.

Nothing is known about Moritz's life between 1896 and 1908. The only exception are a pair of tickets to the Paris 1900 Exposition Universelle preserved with family papers, suggesting that he may have travelled to Paris at the age of 19 to attended the World Fair.

Exposition Universelle, Paris,1900

Constantinople

In the summer of 1908, Moritz and his brother Haim left Ruschuk and moved to Constantinople.

The event is mentioned in by David Rimon's "HaMaccabi Be'Artzot HaBalkan" (The Maccabi in Balkan States), p96:

"A few weeks after the Young Turk Revolution [July 1908], the brothers Haim Abraham and Moritz Abraham, members of Maccabi Ruschuk in Bulgaria, came to Constantinople. The brothers immediately went to work and devoted much of their time and energy to the development of the association."

Life in Constantinople

In Constantinople, Moritz owned a succesful import/export business with his oldest brother, Haim, fittingly called "Abraham Freres". The company imported a variety of small manufactured products from Germany and neighboring countries, such as razor blades, iron padlocks, shoe polish and paper envelopes all over the Levant.

He was variously described as "Commissionaire" (in the French language "Annuaire Oriental"), "Merchant", or wholesale merchant.

Maccabi in Constantinople

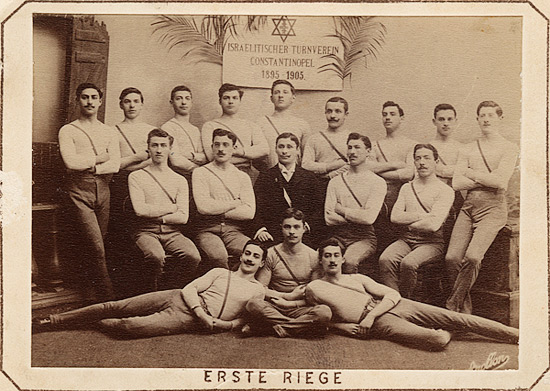

Moritz was involved with the Ruschuk Maccabi Sports Club, as noted by David Rimon. In the family collection is this card, celebrating the 10th anniversary of the "Israelitischer Turnverein Konstantinopel". It's not clear what was Moritz's connection with this event, however, since belonged to Maccabi in Bulgaria, he may have participated in some fashion to the anniversary in Constantinople.

Card: Tenth Anniversary of the Israelitischer Turnverein Konstantinopel

The "Israelitischer Turnverein Konstantinopel" (Israelite Gymnastic Association of Constantinople) was founded in 1895 in Constantinople by Jews of German and Austrian extraction who had been rejected from participating in other social sport clubs. It would eventually evolve into the Maccabi Sports Club.

After his arrival with his brother Haim in Constantinople, his participation in the club is better documented. David Rimon, in "HaMaccabi Be'Artzot HaBalkan" (The Maccabi in Balkan states) states:

"[...] the brothers Haim Abraham and Maurice Abraham, members of Maccabi Ruschuk in Bulgaria, came to Constantinople. The brothers started working immediately upon their arrival and contributed a lot of their time and energy to the development of the [Maccabi, DA] association."

[...] "Under the influence of a few Zionists who were in Constantinople at that time, the Jews launched an internal propaganda for nationalism and Zionism. Among these Zionist influencers were Dr. David Marcus, rabbi of the Ashkenazi community, and Dr. Victor Jacobson, a representative of the Zionist General Council in Constantinople and director of the Anglo-Levantine Bank. [...] A few months after the [July 1908 Young Turk] Revolution, Ze'ev Jabotinsky came to Constantinople. The influence of these Zionist leaders led by Jabotinsky, as well as the two Maccabis who came from Bulgaria [Haim and Moritz Abraham], caused a complete change in the character of the "Israeli Gymnastics Association", which in September 1908 already enacted a "national" [read "Zionist"] constitution."

Moritz Abraham with Maccabi members, Constantinople (lying on the left).

Sitting on pommel horse in the center is Moritz Abramovitz, Chairman of the association.

This photo is on a postcard addressed to "Herr Abraham, Isr. Turnverein, Constantinople" and was mailed on July 24, 1908 from Munich. This would indicate that Moritz may have been in Constantinople, and had already joined the sports club before the Young Turk Revolution, which had started in July and ended on July 24, when Sultan Abdul Hamid II capitulated and reinstated the country's constitution.

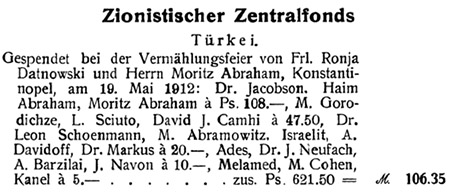

In the April 23, 1915 issue of l'Aurore, a pro-Zionist Jewish weekly published in Constantinople, a short notice about the yearly Maccabi assembly mentioned an "M. Abraham", I assume meaning Moritz Abraham.

M. Abraham appears as one of three advisors, although it's not clear what his responsibilities entailed. Interestingly, his brother Haim is not listed, maybe indicating that he had stopped participating in the affairs of Maccabi by then.

Jewish Gymnastic Association - Maccabi

Pera branch

The yearly general assembly of the Pera branch of the Jewish Gymnastic Association Maccabi was held on Sunday April 18 in the premises of B'nai B'rith. [...] The assembly then proceeded to the election of the new commitee which is made up of the following members:

Manager: M. M.Abramowitz

[...]

Advisor: A. Ziffer

" : M. Abraham

The last mention of Moritz in connection with the Maccabi association places his involvement in the early 1920s, before the dissolution of Maccabi by the Turkish governement in 1923.

David Rimon, p106: "In the last years of the existence of the Maccabi, it was headed by Moritz Avraham."

I can't however confirm this statement as I don't have any other corroborating evidence. Since a Moritz Avramovitch had previously led the group, it is not impossible that Rimon could have confused the two names.

Zionist Activism

Moritz, like his brother Haim, was a Zionist, and was active in several such organizations in Constantinople from his arrival in 1908 until the family's move to Germany in 1922/1923.

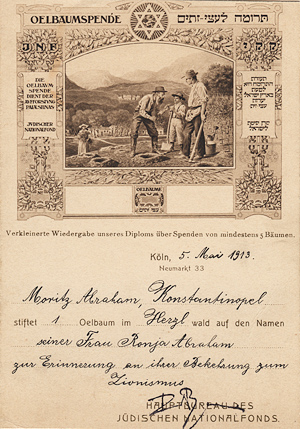

On the first anniversary of his marriage, Moritz purchased an olive tree in the Herzl forest in Jerusalem "for his wife, to commemorate her conversion to Zionism."

Tree certificate from the JNF, May 1913

This doesn't necessarily mean that Moritz considered immigration to Palestine. According to "Jews, Turks, Ottomans", by Avigdor Levy:

"[...] little evidence to suggest that Turkish Zionists were very concerned by the emigration to Palestine". [...] Turkish Zionism tended to be more cultural than political. It was a search for a "national" identity at a time when other religious communities in the empire were asserting their own national identities."

B'nai B'rith

In 1911, a local lodge of the international B'nai B'rith order was created in Istanbul. Moritz joined the lodge, as did his brother Haim, along with many prominent members of the community. The B'nai B'rith would become one of the most active Zionist organizations in Constantinople.

Aron Rodrigue, in "The Alliance and the Emergence of Zionism in Turkey" writes:

Grouping some of the leading members of the Jewish bourgeoisie, whether Sephardic or Ashkenazic, the lodges were philanthropic organizations designed to coordinate the charity and mutual help activities within these cities. They became particularly active in helping the needy among Turkish Jews during the Balkan wars of 1912-1913 and during World War 1. They soon became influenced by the activities of the many Zionists who joined the organization and who were successful in using it as yet another base of agitation against the Chief Rabbi Nahum.

[...] When the forced closure of many foreign institutions of secondary institutions upon Turkey's entrance into World War I threatened to leave many Jewish students without schools, the Constantinople lodge created a Jewish lycée in 1915, the first such Jewish institution in Turkey.

The lodges of the B'nai B'rith [...] went from strength to strength in Turkey in the years following World War I. By the early 1920s, they held all communal affairs in their hands. [...] the B'nai B'rith lodges were centers of extraordinary activism and enterprise in local communal affairs. Between 1908 and the early 1920s, the Alliance network had been dethroned from its position at the center of communal dynamism among Turkish Jewry by the class that it itself had brought into being.

Federation Sioniste d'Orient

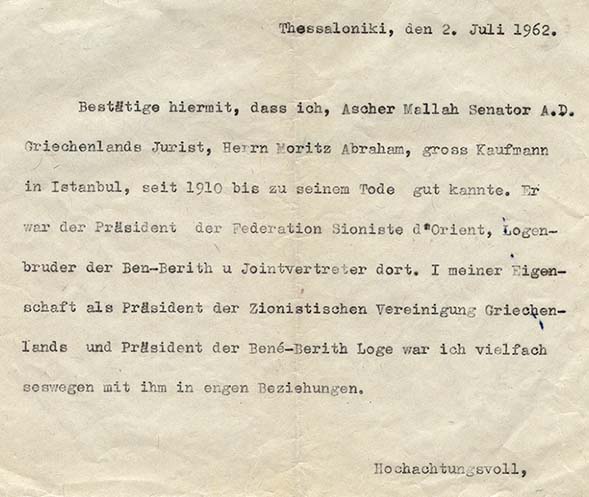

According to a 1962 testimonial written by his brother-in-law Asher Mallah, Moritz was the President of the "Federation Sioniste d'Orient" in Constantinople.

Letter from Asher Mallah mentioning Moritz's activities with the Federation Sioniste d'Orient, B'nai B'rith and the Joint.

Thessaloniki, July 2, 1962.

I hereby confirm that I, Ascher Mallah, Lawyer and Senator of Greece, knew Mr. Moritz Abraham, wholesale merchant in Istanbul, very well from 1910 until his death.

He was the President of the Federation Sioniste d'Orient, Lodge brother of the B'nai B'rith and Joint representative there.

In my capacity as President of the Greek Zionist Association and President of the B'nai B'rith Lodge, I was in close contact with him on many occasions.

The "Federation Sioniste d'Orient" (הסתדרות ציונית של המורח קושטא) was created in 1919 and recruited 4,000 members in Istanbul, but stopped its activities around 1922 or 1923. In 1923, after the proclamation of the Turkish Republic, all Zionist activities became prohibited and Zionism became an underground movement. While active, FSO published "La Nation", a periodical in French.

As an association with limited regional scope ("the Orient") that was active only for a few years, it seems to have left very little traces and little documentation seems to have survived. The only traces of the FSO's activities seem to be contained in the issues of its official publication, La Nation, that I haven't been able to access yet.

When I first found this document, I hesitated to take it at face values as I had never heard about my grandfather's involvement in Zionist activities. Not only had this never been mentioned at home, but I also couldn't find any information on the FSO to confirm.

Since then I have uncovered enough indications that my grandfather did indeed play a role, albeit rather minor, in the Constantinople Zionist groups to take Ascher Mallah's statement seriously.

The Joint

Another interesting detail in this document is the mention of Moritz being "Jointvertreter" = "Joint representative", which I assume means representative of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, the Jewish relief organization commonly known as the Joint, or JDC.

The digitized archives of the JDC contain correspondance from 1915 to 1923 concerning relief provided to the Jewish community in Constantinople. From 1915 to 1918, it appears that the Joint was working with "prominent members of the Jewish community" as its local intermediaries, such as Chief Rabbi Nahum, Dr. Markus, Rabbi of the Ashkenazi Congregation, or with the director and members of the Grand Lodge of the B'nai B'rith. There are no mentions of a local branch or representative of the Joint.

Starting 1921, mentions about a local branch of the Joint appear, and a letter from July 1921 mentions that Dr. Tiomkin is representing the Joint in Constantinople. If Moritz was indeed the representative of the Joint in Constantinople, I don't know when this would have been, or for how long. So far, I haven't been able to confirm Ascher Mallah's assertion.

Zionist Congresses

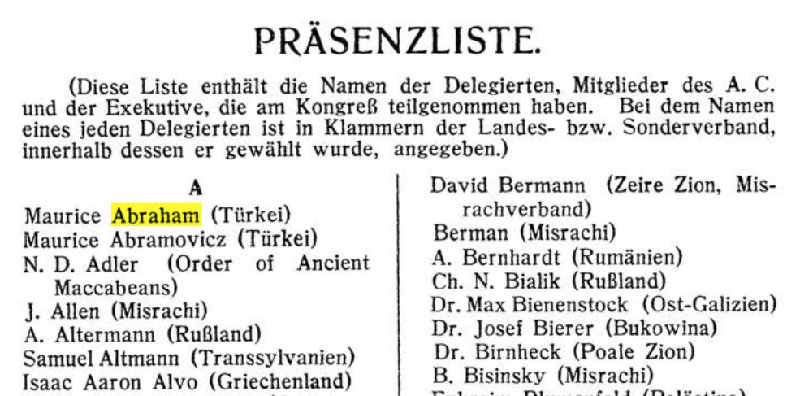

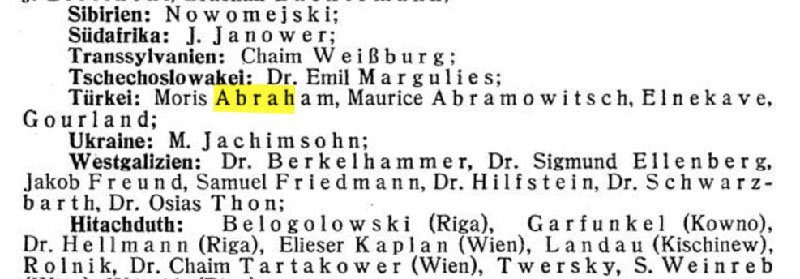

The transcript of the Twelfth Zionist Congress held in Carlsbad from 1 to 14 September 1921 lists Maurice Abraham as one of five delegates from Turkey. Among the other delegates from Turkey are two familiar names: Maurice Abramovicz, a friend and colleague in the Maccabi association, and Dr. Israel Caleb, a friend of the family who was also mentioned in Aaron Aarohnsohn's diary.

List of delegates to the 12th Zionist Congress, 1921.

List of delegates who voted "Yes"

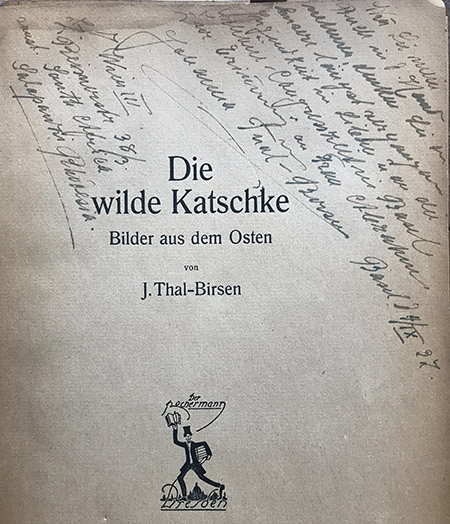

An inscription in a book by Johanna Thal-Birsen, "Die wilde Katschke: Bilder aus dem Osten" to my grandmother provides some circumstancial, although perhaps flimsy, evidence that Moritz may also have attended the 15th Congress in Basel in 1927, although this would have been as a spectator only as his name doesn't appear in the list of delegates. (Johanna Thal-Birsen was a writer and journalist from Libau.)

Inscribed first page of "Die wilde Katschke: Bilder aus dem Osten" by Johanna Thal-Birzen on the occasion of the 15th Zionist Congress in Basel, 1927.

"If you hold my book in your hand, think of our long gone youth in Libau and to the pleasant Congress time in Basel.

In memory of Mrs. Abraham,

Johanna Thal-Birsen Basel 4 September 1927"

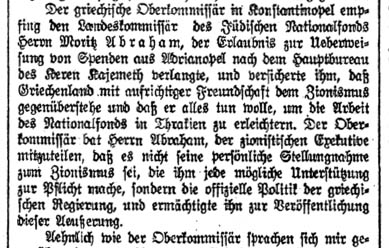

Another document about Moritz's involvement with a Zionist organization is a paragraph from the Wiener Morgenzeitung dated July 27, 1922, where Moritz is listed as the "National Commissar of the Jewish National Fund":

Wiener Morgenzeitung, 27 July 1922

(Source: Bernd Philipsen.)

"The Greek High Commissioner in Constantinople received the National Commissar of the Jewish National Fund, Mr. Moritz Abraham, who had requested the permission to transfer donations from Adrianople to the main office of Keren Kayemet, assuring him that Greece had a genuine friendship for Zionism and that he wanted to do everything to facilitate the work of the National Fund in Thrace. The Chief Superintendent asked Mr. Abraham to inform the Zionist Executive (?) that it was not his personal opinion on Zionism that made his assistance possible, but the official policy of the Greek government, and authorized him to publish this statement."

Marriage

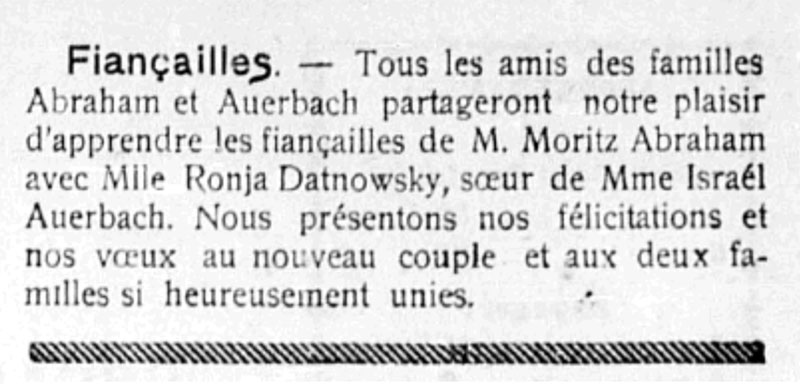

Moritz was introduced to his future wife Ronya Datnowsky, a young woman from Latvia, through Israel Auerbach and his wife, Berta - Ronya's older sister.

Ronya's mother had died in 1909. Shortly thereafter, Ronya and her two younger siblings, Eva and Israel, came to Constantinople to stay with their older sister Berta. Berta's husband was a prominent member of the Jewish Community and through his contacts, Berta was able to arrange for her sister Ronya to find a "suitable" husband.

Ronya and Moritz got engaged in December of 1911.

Ronya and Moritz's Engagement Announcement in L'Aurore, Constantinople, December 22, 1911

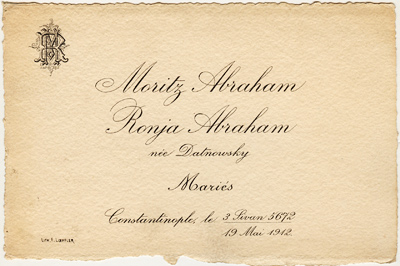

Moritz and Ronya Datnowsky were married in May 19, 1912 in Constantinople.

Ronya and Moritz, Constantinople, May 1912

Wedding announcement, in French. 1912

Wedding announcement, in German. 1912

The May 31, 1912, issue of Die Welt, the official Zionist organ, published the list of people who had made a donation to the central fund of the Zionist organization on the occasion of Moritz's and Ronya's marriage. This list provides a valuable insight into their social circle at that time. In this list are familiar names of prominent members of various Zionist and Jewish organizations in Constantinople. Dr. Victor Jacobsonwas the representative of the Zionist General Council in Constantinople and director of the Anglo-Levantine Bank. Lucien Sciuto was the editor of l'Aurore, the Zionist weekly of the capital. Abramovitz was one of the leaders of the Maccabi association. Dr Markus was the Rabbi of the Ashkenazi community and an active member of several Zionist groups. Gorodische is a name I remember from my chidlhood: Mrs. Gorodische was a friend of my grandmother's from Constantinople, who met again in Germany in the 20s, then in Paris in the 30s. Other names include: A. Barzilai (possibly related to Jacques Barzilai of of the Maccabi leadership), Melamed (possibly Meir Melamed, from Maccabi Bulgaria), David Camhi, Dr. Leon Schoenmann, A. Davidoff, Dr. Neufach, J. Navon, M. Cohen, Kanel, Ades and Israelit.

Moritz and Ronya lived in Pera (now Beyoglu), a residential area. Their address (confirmed between 1917 and 1921) was:

Sourp AgopArif Pascha Han

Appartement #5

Arif Pacha

Appartment #5

Elmadag 14 (Pancalti)

A similar address, but with a different Han name, was used on a postcard from Isrolke Datnowsky in April 1915. I assume this was meant to be the same location, in which case Moritz and Ronya lived in the same apartment at least from 1915 to 1921:

Surp-AgopBerberian Han 4

According to Mehmet Sadettin Fidan: "Sourp Agop and Elmadag are the same place. Arif Pasha Appartment is in Elmadag Street, located in Pera (now Beyoglu)"

This photo, showing the funeral procession for a German sailor, was taken from the apartment of Moritz and Ronya Abraham in 1913.

"Funeral for a German seaman"

View from Moritz and Ronya's apartment in Constantinople, 1913.

Children

In 1917, Moritz' and Ronya's first child, Gedeon (Gisi), is born

Moritz and Gisi, Constantinople, 1917 or 1918

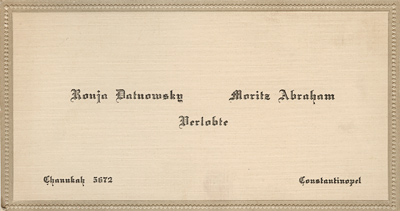

22 March, 1918, L'Aurore, the pro-zionist Jewish weekly, announces that Moritz and Ronja have set up a prize to commemorate their son Gideon's first birthday, which will be awarded every year to students from four schools belonging to the "Hilfverein der Deutschen Juden" showing excellence in Hebrew. Four students are selected for the first time in 1918.

L'Aurore, 22 March 1918

In 1918, a second son, Uriel (Uly), was born

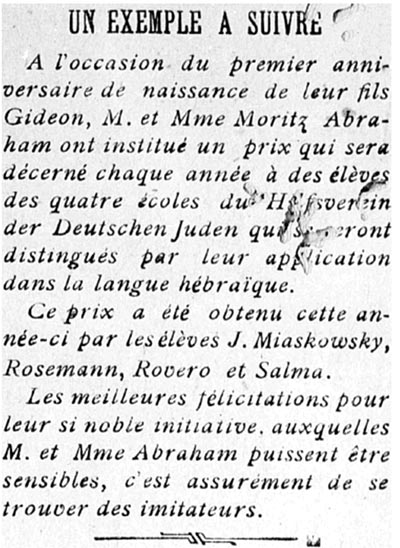

Moritz with Gisy and Uly, Constantinople, 1919

Moritz with Gisy and Uly, Constantinople.

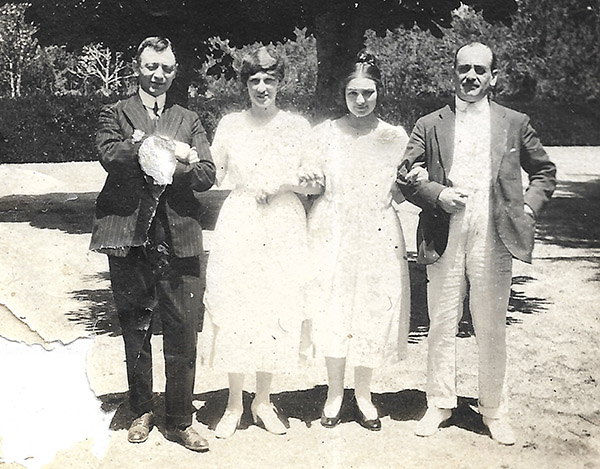

Dr. Caleb, Mlle Lowy, Mlle Wertheimer and Moritz Abraham, Erenkeuy, 1921.

Dr. Caleb, member of the B'nai B'rith lodge is mentioned in the January 1st, 1915 issue of l'Aurore as a belonging to the committee responsible for the establishment of the Jewish high-school. He is also mentioned in Aron Aaronsohn's diary ("Dr. Caleb will give me injections against cholera."). Mlle Wertheimer is possibly Elfrida (Mädi) Wertheimer, Mony Abraham's wife; or possibly her sister Alice. Erenkeuy is a little village at about half an hour ride from Constantinople on the Asiatic side

Nationality

Moritz was born in Bulgaria - a province of the Ottoman Empire that had achieved autonomy in 1878 and would achieve full independence in September 1908.

I suppose that Moritz was an Ottoman citizen, as Bulgaria - although an autonomous province by the time of his birth - was still under Turkish control. However, he would have had to become a Bulgarian national when Bulgaria became independant.

During the Balkan Wars of 1912, Bulgaria and Turkey were ennemies, raising the question of where his loyalty would have been. By then, he resided in Constantinople, and Ronya, his Russian wife volunteered as a war nurse with the Turkish Red Crescent, suggesting that he was - either from self-interest, conviction or from cultural reasons - closer to Turkey than to Bulgaria.

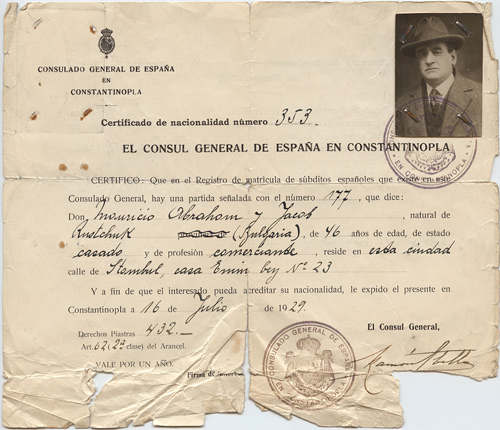

However, the birth certificate for his first son Gisy was drawn by the "Community of Foreign Jews in Constantinople", indicating that he didn't hold Turkish nationality. Actually, the only passports under his name that have survived were issued by the Spanish consulate in Constantinople.

How did this happen?

The reasons and circumstances for his acquiring a new, somewhat artificial nationality - he had never even set foot in Spain - are not clear. This decision however would later prove extremely fortunate as it would provide him and his family some unusual consular protection during the German occupation of Paris during WWII.

I remember my mother telling me that after WW1, people where he lived were able to chose their nationality. According to her, he had at first considered applying for the Austrian nationality, because it seemed more desirable to have an Austrian passport than a Turkish one.

Why Austria? Article 1 of the peace treaty of Passarowitz signed between Austria and Turkey in 1718 granted Jews who were Turkish subjects the right to live and trade freely in Austria. This regulation was again confirmed in the Peace Treaty of Belgrade in 1739, and this is how Turkish Jews began to enjoy unrestricted movement in Austria, with a colony of Turkish Jews settling in Vienna in the eighteen century. This treaty worked both ways, granting similar protection to Austrian subjects in Turkey.

Were the terms of this treaty still recognized in the early twentieth century, and was this the basis for his attempt at Austrian nationality?

However - still according to my mother - upon learning that as an Austrian national he would have to serve in the army of the Emperor, he concluded that he was not so eager to become an Austrian citizen after all, and decided to apply for a Spanish passport instead.

Note: my mother's explanation doesn't seem to make complete sense, at least as described above, as there would not be an Emperor to fight for after the end of WW1. It is possible that Moritz could have considered the Austrian nationality before WW1 - then the issue of becoming a soldier would have made sense. It's also possible that he may have considered the option after WW1, but judged that after the defeat and the disintegration of the Empire, the Austrian nationality was not so attractive after all.

It's also possible that the whole Austrian nationality story is wrong altogether...

According to my father, Western European powers, including Spain, wanted to claim as many citizens as possible in the Ottoman Empire - in order to increase their position in regards to the Capitulations which gave them influence and economic rights in Turkey.

Coming from a town were all the Jews were Sepharad and spoke Ladino, he was considered by Spain a descendant of Jews expelled from Spain in 1492, and thus could claim Spanish citizenship.

However, the Primo de Rivera law which granted Spanish nationality to descendants of Sephardic Jews was passed in 1924; Yet Moritz and his wife Ronya already held Spanish passports by 1922. It seems however that the Spanish Consulate in Constantinople had already been providing passports to Sephardic Jews in the region before the existence of the 1924 law.

According to "The Spanish Consulate in Istanbul and the Protection of the Sephardim (1804-1913)" by Pablo Martín Asuero, Sepharad Jews were already granted Spanish protection by the Consulate in Constantinople before the 1924 law. According to this document, a number of Jews had left the new Balkan states in 1912/1913 to settle in Istanbul, and some of them requested the protection of the Spanish consulate. Asuero mentions "... 70 records of Sephardic protection that date to 1913 [... containing] information on around 220 people [including] the names of the spouses and children."

It seems that the request for Spanish protection was generally granted to Jews of Spanish origin, especially if they had sufficient means - their protection then beeing deemed beneficial for Spain.

The following could certainly have been applied in Moritz' case:

"The applicant has a good background and a wealthy position which in his capacity as trader and trade representative can serve Spanish interests."

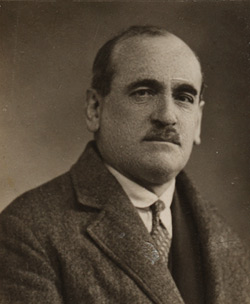

Moritz, ca. 1921

Düsseldorf

According to my mother, Ronja didn't want to live in Turkey and argued that since Moritz' business operated between Germany and Turkey, the family might as well live in Germany, which corresponded more to her lifestyle expectations.

In 1922, Moritz purchased an empty lot in Düsseldorf on LindenmannStrasse, across from St Pauluskirche.

LindenmanStrasse, Düsseldorf. The empty lot where the house was built.

Düsseldorf is close to Solingen, a region known for its cutlery/metal blade industry; the choice of Düsseldorf may have been caused - at least in part - by its proximity to several suppliers of Abraham Freres (Germania-Werk, Kamphausen & Plümacher, etc.)

It seems that Ronya went to Germany with Uriel and Gisy first, while Moritz stayed in Constantinople, taking care of business. While the house was under construction, Ronya, the children, and their nurse stayed in a pension in Düsseldorf. After the house was finished, the family moved in and, in December 1922, Moritz came to Düsseldorf.

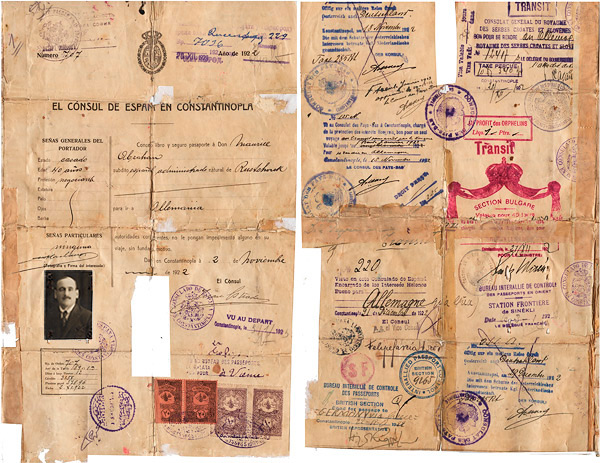

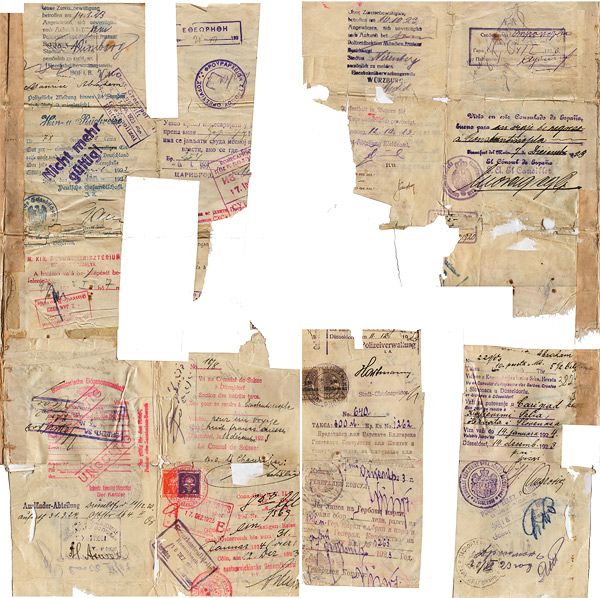

Moritz's Passport, 1922

This travel document was delivered by the Spanish consulate in Constantinople in November 1922. It consists of four pages covered with stamps, showing Moritz's travels to Germany between December 1922 and January 1923, with transit through Serbia, Greece, Hungary, Holland and more... A few more stamps are for travel to Vienna, Constantinople and Bulgaria in 1923.

According to a December 8, 1922, letter from Elfriede (Mädi) Abraham (wife of Mony) to Ronya, Moritz's departure had been delayed because:

"Something happened that nobody could have predicted. [...]"

"Moritz had to postpone his trip. He already had his passport with all his visas [...]"

"Now he's not going to leave until the situation with Haim is taken care of. He is hoping it will be resolved in about 12 days."

The acrimonious dispute between Haim and Moritz resulted in their company Abraham Freres being dissolved. From now on, Moritz would continue to operate a similar business on his own from an office in the same location.

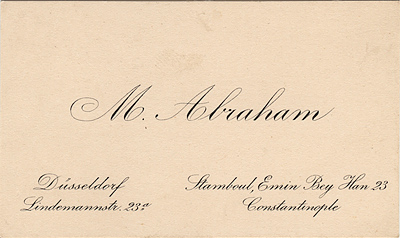

Moritz Abraham's business card: Düsseldorf & Constantinople - 1920s.

Moritz's primary residence was now in Düsseldorf but he still retained an office in Constantinople: Stamboul, Emin Bey Han 23, although it was now reduced to a single office (#23).

23 LindenmanStrasse, Düsseldorf. The house is the first one on the corner.

The house in Düsseldorf

The house in Düsseldorf

The living room, 1925

The Dining Room and "Winter Garden", LindenmanStrasse. 1924

Photo Marcel Fresco.

In 1923 or 1924, Moritz sold an appartment in the Shahkulu district in Constantinople. The address doesn't correspond to where the family used to live, so it's not clear what this appartment was, whether an investment property or an apartment belonging to a relative. (Note: need scan?)

1927

The only photo of Ronya and Moritz together after leaving Constantinople.

Ronya and Moritz with friends, Bachrach on the Rhine, 1927

Moritz and Ronya's lifestyle was somewhat extravagant - Uriel said that at one point they had up to five employees in the house: a gardener, a butler, a chauffeur, a nurse and a cook. This was most apparently Ronya's idea.

This lifestyle however didn't last. According to my mother, one evening Moritz came home and announced to the family: "It's over - it's all gone." Whether this story is real or apocryphal, something did happen with Moritz's fortune. All his money was apparently invested in the stock market, and he lost it all - seemingly overnight.

According to the story I was told, this loss of money prompted the family to leave Düsseldorf and move to Paris.

A few things aren't clear though. I was told that this coincided with the 1929 market crash; however, there is a certificate "de fin de séjour" (end of stay) dated December 24, 1928, indicating that the family was planning to leave Düsseldorf and go to Paris as early as the end of 1928.

This either means then that this reversal of fortune had happened before the crash of October 1929 - the result of bad investments maybe (my mother said that the fortune was "all on paper"). Otherwise, it would mean that they had planned to go to Paris before losing their fortune.

The other question is: why leave? and why Paris? I never heard that the rising threat of Nazism had been the reason for the family's departure, although it might have been a factor. Bertha, Ronya's sister, was now living in Paris, but it's not clear why that would have been a sufficient reason to uproot themselves once more.

Confusing the timeline, there are some photos with Ronya and the children in Düsseldorf dated 1930. The earliest photos of the family in Paris date from 1930, so it's not clear why they had this "end of sojourn" certificate dated December 1928.

Registry Entry - January 1929:

| Registry Book 1928-1930 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family Name | Given Name | Name of Parents | Date of Birth | Place of Birth | Profession | Registry Date |

| Abram | Morisyo | Mamo and Lea | 23 January 1883 | Ruse (Ruschuk) | Merchant, J. Emin b-h. | 29 January 1929 |

In July 1929, Moritz still retained the same business address - Emin Bey Han, No 23.

Although the Abraham Freres had ceased to exist since the early 20s, Moritz continued to be involved in a similar import business.

Alex Mallat recalled that, while in Düsseldorf, Moritz had owned a large steel company named MORA, however I've never heard this mentioned at home nor have I found any documents to confirm this.

Alex' recollection may actually have come from Morris Halle's memoir:

"Moritz Abraham was in the steel business in Germany. At one time he produced safety razor blades which my father tried to sell in Latvia. The attempt was unsuccessful, but we had thousands of sample blades about the house. In fact, we first began to buy blades several years after we came to America. Until that time, the MORA blades that my father had at home made such purchases unnecessary."

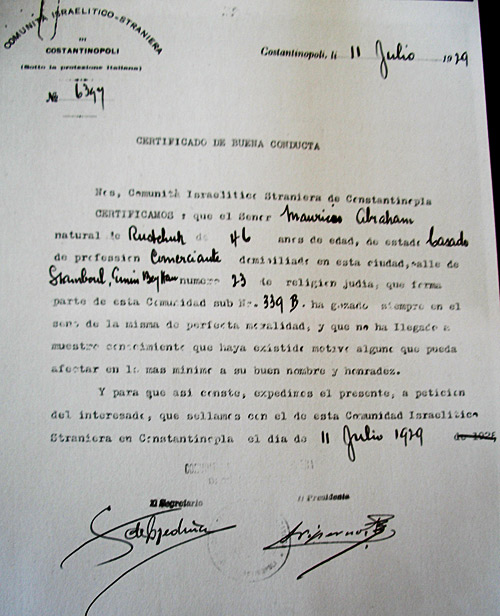

The following "Certificate of Good Conduct" was issued by the "Association of Foreign Israelites of Constantinople" for Moritz:

Certificate of Good Conduct, 1929.

Constantinople, July 11, 1929

Foreign Israelite Community of Constantinople.

Certificate of good conduct

We, the Foreign Israelite Community of Constantinople, certify that Mr Mauricio Abraham, originally from Ruschuk, 46 years old, married, merchant, residing in this city, Stamboul, Emin Bey Han, number 23, of Jewish religion, is part of this community (under the number ?) 339 B.

He has always enjoyed the same perfect moral standard and to our knowledge there is no motive that could affect in the most minimal way his name and honor.

Consequently, we expedite this petition for the interested party and we affix our seal of the Community of Foreign Jews of Constantinople.

11 july 1929.

It is not clear what this document was usef for. It may have been a prerequisite for acquiring the Spanish nationality. However, Moritz had already been using a Spanish passport as early as 1922. Maybe he had only been "under the protection" of Spain until then, and was now applying for the full-fledged Spanish citizenship? Was this because, with the move to Paris, he would stop having also a presence in Constantinople and would now need something more official?

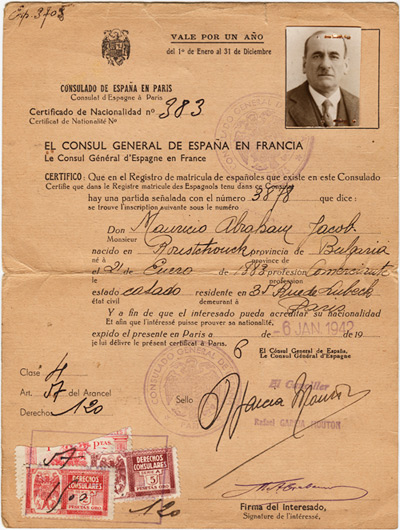

Moritz Abraham's Spanish Nationality Certificate, 1929

Moritz, late 1920s

Paris

The family moved many times after their arrival in Paris, athough they always remained in the 16th arrondissement. Their first address was rue des Marronniers. In 1930 they lived 117 boulevard Exelmans, then moved 67 rue Erlanger. This was apparently a sublet, as a card from Gisy that year was addressed to "Abraham, Chez Santon".

The entry cards for Moritz ("Mauricio") kept in the Paris Police Archives indicate that he was then without a profession.

The family's lifestyle was clearly a far cry from what they had enjoyed in Düsseldorf. The appartments were probably not large, as Gisy and Uriel first attended Lycée Lakanal, a boarding school on the outskirts of Paris. (There may have been other reasons why they were sent to a boarding school, which had a large contingent of foreign students.)

By 1933, the family moved again, this time to 122 boulevard Murat, again in the 16th arrondissement.

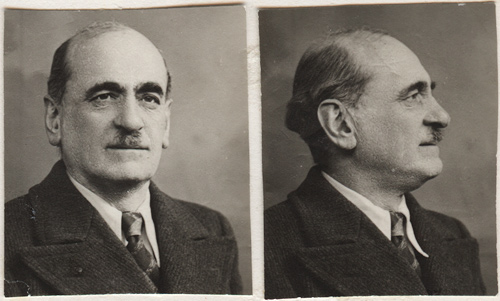

Moritz, Paris, 30s

Passport, 1934

Every few months, Moritz was away for his business. Over a six-month period, Moritz travelled to these locations:

July 1934: Austria, Hungary, Yugoslavia, Switzerland, Serbia

October 1934: Austria

December 1934: Romania, Austria, Switzerland, Hungary

In September 1939, the family moved on last time, Rue de Lübeck, as always in the 16th Arrondissement.

1940-1943

In May 1940, Germany invaded France. On June 3, 1940, the Germans bombed Paris, and half of its population joined a mass exodus, fleeing the German advance. Among them was Moritz's son, Uriel, who managed to reach the South of France by bicycle then boarded a ship to Casablanca where he would spend the war. Moritz and Ronya however decided to remain in Paris.

Why they decided to stay is a mystery. Moritz had been involved with Zionist activism during his Constantinople days, his brother Haim had moved to Haifa in 1932, while Ronya's sisters had done the same - Liska Mallah in 1934 and Bertha Auerbach in 1937. Did Moritz ever consider immigrating but Ronya refused? Did he underestimate the dangers that lay ahead for Jews under Nazi rule? Or did he not have the will to leave, maybe due to ill-health? My mother would later explain Moritz's death in 1943 by saying that he hadn't been well and had been bed-ridden for a long time.

Moritz, 1939

How Moritz experienced the German occupation of Paris is a complete mystery. No oral history and no documents, whether letters or official papers, remain to give any insights on what happened to Moritz between 1940 and 1942.

Moritz and Ronya continued to live at the same address, 35, rue de Lübeck.

Moritz's certificate of Spanish nationality, 1942

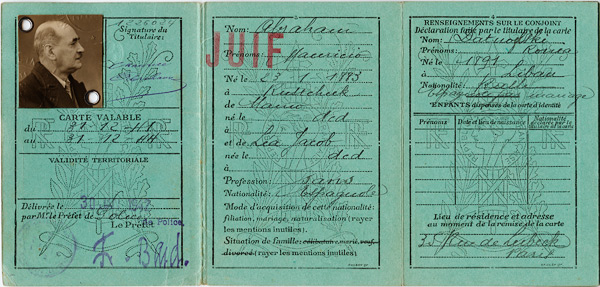

By 1942, according to this Alien Identification Card, Moritz was not working - most likely not by choice but because as a Jew he was not allowed to own a business anymore.

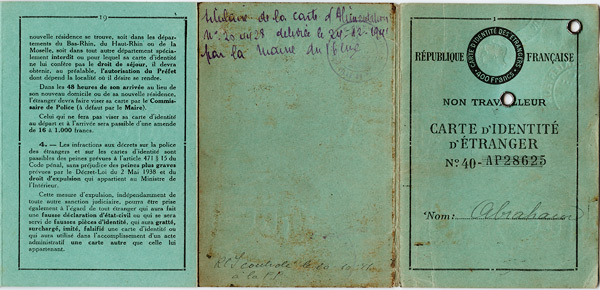

Moritz's Alien ID card. Paris, 1942

Alien ID Card

Non-Worker

Nationality: Spaniard

Profession: none

JEWSpouse: Ronya Datnowski

Nationality: Russian, Spaniard by marriage

On July 16 and 17, 1942, the French Police, under Nazi orders, rounded up over 13 000 foreign Jews in Paris, (Rafle du Vel' d'Hiv.) Holding Spanish passports, Moritz and Ronya were not targeted.

As a child, I had been told that my grandparents had been protected during the German occupation thanks to the official policy of Franco's Spain, which didn't have racial laws and would't let Germans extend their policies to Spanish citizens.

However, it appears that the reason they were protected was because of the action of Bernardo Rolland, Consul General of Spain in France from 1939 to 1943.

Bernardo Rolland resisted German orders and directives from his own government, instead providing letters of protection for Jews with Spanish nationality, the great majority of whom actually came from the Balkans, like Moritz Abraham.

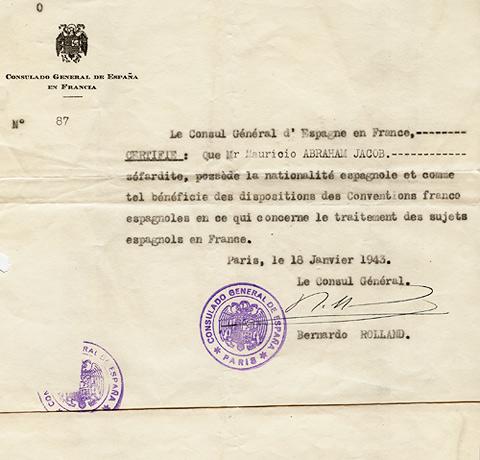

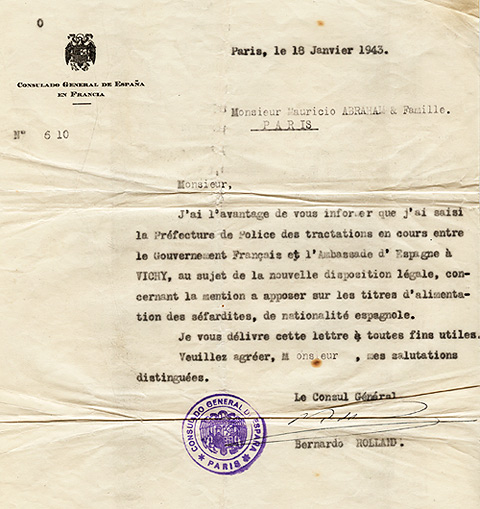

Letter from the Spanish Consul Bernardo Rolland, January 1943

The Spanish Consulate in France certifies that Mr Mauricio ABRAHAM JACOB, a Sepharad, is a Spanish national, and as such benefits from the provisions of the French-Spanish covenents concerning the treatment of Spanish subjects in France.

Paris, January 18, 1943.

The General Consul

Bernardo Rolland

Letter from the Spanish Consul Bernardo Rolland, January 1943

Paris, January 18, 1943.

Mr Mauricio ABRAHAM and family.

I am pleased to inform you that I have contacted the Police Department regarding the ongoing negociations between the French Goverment and the Spanish Embassy in Vichy concerning the new legal regulations regarding the reference(*) to include on food tickets of Sepharads with the Spanish nationality.

I send you this letter for all intents and purposes.

Best salutations.

The General Consul,

Bernardo Rolland*: meaning stamping the word "Jew".

The following excerpts are from www.raoulwallenberg.net

Bernardo Rolland, Consul General of Spain in Paris since 1939, distinguished himself for defending the Jewish people, and occasionally confronting his ambassador, José Felix de Lequerica, who wasn't willing to excessively contradict the pro-nazi government of Vichy and the Germans. After Vichy adopted the "Statut des Juifs" (which distinguished the Jews from the rest of the population), imposing them all kind of restrictions, Rolland concentrated his efforts in avoiding the confiscation of their goods.

In august 1941, Rolland made an active intervention in favor of 14 Sephardic Jews that had been arrested and sent to the concentration camp of Drancy. By the same date, Rolland assumed a risky initiative documented in a German memo dated September 14th. He appealed to the German authorities of Paris, proposing the transfer of 2000 Jews (included the ones in Drancy) to the Spanish Morocco in the term of a few weeks. After that, though without much success, he tried to ease the exit of the Jews from France, while continuing with his denouncements against persecutions which were more severe every time.

In 1942, Rolland's measures succeeded. It was impossible for the authorities of Vichy to confiscate the Jewish people's patrimony

Letter by Bernardo Rolland, the Spanish Consul General to France in Paris, in regards to anti-Semitic laws imposed on all Jews, including Spanish nationals living in France, by the French Government at the behest of the Germans in 1942:

"Spanish law does not discriminate among [Spanish] citizens because of their religion, and for that reason it regards Jews who *originally* came from Spain as Spaniards, despite their Jewish religion. For this reason, I would be grateful if the French authorities and the occupying power would be good enough not to impose upon them those laws that apply to Jews"

Source: Note 49 CDJC, 32/180A, reply from Rolland, July 23,1942, to letter from the Commissariat General aux Questions Juives, July 22, 1942

(Of course, neither Moritz nor Ronya came from Spain, making Bernardo Rolland's protection all the more impressive.)

From: VISAS for freedom (pdf)

In October 1940, the Spanish Consul in Paris, Bernardo Rolland, informed the Minister of Foreign Affairs about the new anti-Jewish measures that also affected the 2,000 Sephardic Jews with Spanish nationality residing in the French capital. The Statut des Juifs envisaged a gradual stepping up of discriminatory measures, viz., registration, expropriation and, ultimately, detention and deportation.

By means of "letters of protection" Rolland succeeded in having the Spanish Sephardim excluded from most of the anti-Jewish laws. "There being no Act referring to a Statute on Jews in Spain", wrote Rolland to the Minister on 24th October, "no Foreign State or Authority may classify Spaniards and accept these measures [...]".

However, the Madrid government had no wish to associate itself with the Consul's stance, and on 9th November the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Serrano Suñer, wrote to his Ambassador in Paris, José Felix Lequerica, leaving no doubt as to Spain's position:

"While it is certainly true that in Spain no race law exists, the Spanish Government cannot raise objections, even in the case of its subjects of Jewish origin, to prevent them from being subjected to general measures, its sole duty being to consider itself informed of such measures and, if the worst comes to the worst, place no obstacles in the way of their enforcement by maintaining a passive attitude".In the latter part of 1941, Rolland again wrote to his superiors in Madrid inquiring as to the course of conduct to be followed in the event of the possible confiscation of assets of Spanish subjects of Jewish persuasion. Here, Madrid's reply was more active; however, it did not entail the task of protecting the persecuted parties but rather that of responding to Germany wherever Spanish sovereignty might be encroached upon. In this case, Spain's -not disinterested- position marginally benefited Spanish Jews (nationals and protected persons alike), because Consul Rolland managed to protect their assets and prevent their expropriation, by appointing non-Jewish Spanish administrators.

In August 1941, after a massive raid in Paris in which 7,000 people were apprehended, Rolland interceded to secure the freeing of 14 Spanish Jews who had been sent to the Drancy transit camp. Rolland did not apply the Ministry's restrictive orders regarding establishment of Spanish nationality to the letter, and in some cases also extended consular protection to persons that had the nationality but for a variety of reasons had not been entered on the Citizens' Register created by the 1924 Decree. At all times, the Spanish Sephardic Jews' desperate requests for protection or repatriation were forwarded by Rolland to Madrid.

On January 31, 1943, Moritz died at home.

It was said that he had been sick and bed-ridden for a while, although the nature of his ailment was never described, the only explanation being that, due to the "circumstances" - being a Jew in Paris during the German occupation - "he wasn't well and hadn't received the treatment he needed".

Which doesn't explain much.

This lack of transparency on the actual cause of his death is particularly strange, as I was given more specific information about the death of his brother Mony (uremia). Meanwhile, it seems that Ronya misrepresented the suicide of her brother Isrolke, having told her sister and the family he had died of typhus.

By this time, Moritz must have been quite depressed. Transplanted in Paris, far away from where he had grown, he probably had few, if any, friends. He was not working, and not having been able to regain his footing after losing his fortune in the 1920s, he had been living in very different circumstances from what he had known in his younger years. Probably as a result of this reversal of fortune, Ronya appears to have shown him little love or support. The loss of his first son Gisy had affected him badly. Two of his brothers, Mony and Isak, were dead, and he had had a falling out with his older brother and former partner Haim.

Although Spanish Jews had been shielded from deportations, Moritz had to feel increasingly anxious from his status as a foreign Jew in occupied Paris. By 1943 however, it appeared that that protection might come to an end, which would have been devastating.

Although it is impossible to know for sure, all of these facts have led me to conclude that there is a very strong possibility that an ailing, demoralized Moritz actually ended to his life.

After burying him, Ronya would flee Paris and find a temporary refuge in Spain.

- Special Thanks:

- Mehmet Sadettin Fidan, for providing records related to Moritz Abraham's professional activity.

- Pablo Martín Asuero, for copies of the 1929 "Certificate of Good Conduct" and 1928-1930 Spanish Consulate Registry Book

- Bernd Philipsen, for uncovering a wealth of punlications with references to the Abraham family, including the Wiener Morgenzeitung, 27 July 1922 article mentioning Moritz's role as "National Commissar of the Jewish National Fund".

- References:

- "HaMaccabi Be'Artzot HaBalkan" (The Maccabi in Balkan states), by David Rimon

- "The Spanish Consulate in Istanbul and the Protection of the Sephardim (1804-1913)", by Pablo Martín Asuero

- "Morris in Latvia 1923 - 1940", by Morris Halle (private publishing)

- "De l'Egée et de la Baltique à la Seine", by Alex Mallat (unpublished memoir)

- Aron Rodrigue, "The Alliance and the Emergence of Zionism in Turkey", retrieved from www.doku-archiv.com

- Stenographisches Protokoll Der Verhandlungendes XII Zionisten Kongresses In Karlsbad vom 1 bis 14 September 1921.

JÜDISCHER VERKAG BERLIN

sammlungen.ub.uni-frankfurt.de